The Bahraini people’s struggle continues in spite of the lying, conniving Western governments and their media lackeys, Finian Cunningham writes.

This week marks the 10th anniversary of the Arab Spring uprisings. Two previous commentaries this week have dealt with the geopolitics of those momentous events. This third part below is a personal reflection by the author who found himself unexpectedly embroiled in the maelstrom. It was life-changing…

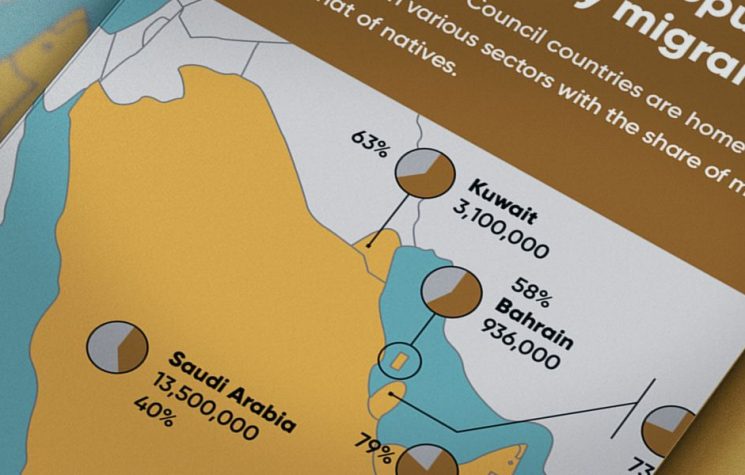

I had been living in Bahrain for two years before the tumultuous events of the Arab Spring exploded in early 2011. Before that turmoil ignited, I was working as an editor on a glossy business magazine covering the Gulf region and its oil-rich Arab monarchies. But in many ways, I hadn’t a clue about the real social and political nature of Bahrain, a tiny island state nestled between Saudi Arabia and the other big Gulf oil and gas sheikhdoms of Kuwait, Qatar, United Arab Emirates and Oman.

During my corporate media employment I enjoyed a charmed life: a hefty tax-free salary, and a swanky apartment with rooftop swimming pool, jacuzzi and gym, which overlooked the sparkling Gulf sea and other glittering buildings that seemed to sprout up from reclaimed spits of land off the coast.

It was all weirdly artificial, if not hedonistically enjoyable. The luxury and glamor, the opulence. Unlike the other Gulf states, Bahrain had a distinctly more liberal social scene – at least for the wealthy expats. There were endless restaurants offering cuisine from all over the world. There were bars that freely sold alcohol which is “haram” in the other strictly-run Gulf Islamic monarchies. There were loads of nightclubs and loads of pretty hookers, most of them from Thailand and the Philippines. It all had the atmosphere of Sin City and forbidden fruit for the picking.

I later realized that Bahrain was not “cosmopolitan” as the business magazines and advertisements would gush about. That was just a euphemism for a vast system of human trafficking. All the service businesses were worked with menial people from Asia and Africa who were cheap and indentured labor. Where were the ordinary Bahrainis? What did they do for a living? In the cocooned expat life, the ordinary Bahrainis didn’t exist. Rich expats were there to enjoy tax-free salaries, glamorous glass towers, loads of booze and, if desired, loads of cheap sex.

My wake-up call came when my so-called professional contract was terminated after two years. That was in June 2010. Like a lot of other expats, my job came a cropper because of the global economic downturn that hit after the Wall Street crash during 2008. Advertising revenue failed to materialize for the magazine I was employed on. The British owners of the publishing house – Bahrain is a former British colony – told me, “Sorry old chap, but we can employ two Indians on half your salary.”

So that was it. I was out on the street. Going back to Ireland was not a realistic option. The economy was crap there too and job prospects dim. So I decided to hang in there in the Gulf and apply for jobs across the region. I downsized to a more modest apartment and lived off some savings. The job hunting was the usual wearying, self-debasing grind. “There’s nothing more than I would desire than to work as editor on your prestigious oil and gas trade magazine in Dubai.” Copy and paste as required for countless emailed job applications.

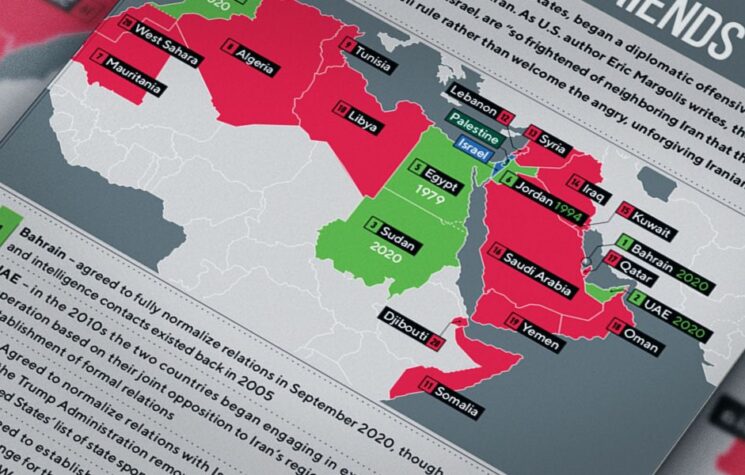

Then came the Arab Spring. The entire region of North Africa and Middle East erupted at the end of 2010, first in Tunisia then in the new year spilling over to Egypt and beyond. Watching TV news was like watching a satellite map of a cyclone sweeping across countries. It was an unstoppable force of nature. There were protests flaring up in Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Oman, the Emirates, and they soon arrived in Bahrain. The rallying call among the masses was for more democratic governance, for free and fair elections, for economic equity.

Little did I know during my earlier charmed expat existence, but Bahrain was a particularly explosive powder-keg. Later, however, I was an unemployed journalist who suddenly found himself in the middle of a storm. It was only then that I began to really understand what Bahrain was all about. I mean the ugly, brutish nature of this “kingdom”.

To be honest, I wasn’t looking for work as a freelance reporter. I had done that in a previous life in Ireland. I was still a journalist, but reporting on political news wasn’t appealing anymore.

During my fruitless job-hunting period for a “dream number” in Dubai, I filled in my time and tried to earn a bit extra by hawking around bars in Bahrain with a guitar and microphone. I had done a bit of that in my previous life in Ireland, not very successfully mind you. But I thought I’d give it a go in Bahrain. On February 14, 2011, I was doing a gig at Mansouri Mansions hotel in the Adliya district of Manama, the capital. It was Valentine’s night. There’s me singing cheesy love songs – Elvis’ ‘I Can’t Help Falling in Love With You’ – and there were hardly any customers. The place was dead.

Then the word came around. “We’re closing early. There’s trouble on the streets.” The whole city was eerily quiet. The Bahrain uprising had begun, not in the capital, but in the outlying towns and villages. On February 14, a young Bahraini man Ali Mushaima was shot dead by state security forces during protests. I was still oblivious to the extent of what was happening.

Overnight the atmosphere in Bahrain was changing to a much more menacing, volcanic one. There was immense popular anger over the young man’s killing.

I was in a taxi in the Juffair area of Manama going to enquire about doing a music gig at another bar. My petty concerns were shattered by the young taxi man who was animated about the protests and the death of Ali Mushaima the night before. The taxi man – Yousef, who I got to know – explained to me about Bahrain’s history. About how the majority of the people are Shia muslims who have lived for centuries under a despotic Sunni monarchy. The Al Khalifa royals were originally from the Arabian Peninsula, a clan of raiders and bandits. They invaded Bahrain as pirates in the 18th century and were made the rulers over the island by the British who wanted a strong-arm regime to look after their colonial possession and sea routes to India, the so-called jewel in the British imperial crown. The Khalifa clan would later become obscenely wealth after oil was discovered in Bahrain in the 1930s, the first such discovery of oil in the Gulf, predating that of Saudi Arabia’s. Over the decades, the Bahraini majority would be marginalized and impoverished by their British-backed rulers.

I asked Yousef, the young taxi man, “So what do you make of all these wealthy high-rise buildings and the glamor of Bahrain?” He replied, “It means nothing to us – the Shia people of Bahrain. We are strangers in our own land.”

Yousef appealed to me to attend a protest that night. It was at the Pearl Roundabout, a major intersection and landmark sculpture in Manama. The protesters were taking their grievances right to the very capital, not confining themselves to the outlying squalid towns and villages where the Shia majority were forced to live in ghettoes by the Khalifa regime.

What I encountered was a revelation. Suddenly I felt I was finally meeting the people of Bahrain. Tens of thousands were chanting for the regime to fall. The atmosphere was electric but not at all intimidating for me. People were eager to explain to this foreigner what life was really like in Bahrain, as opposed to the artificial images that plaster business magazines and Western media advertisements for rich investors.

Then I knew right there that there was a story to be told. And there I was ready and willing to tell it.

The protests were quickly met with more violence from the Bahraini so-called Defense Forces. “Defense Forces”, that is, for the royal family and their despotic entourage. The protesters were unarmed and non-violent, albeit passionate in their demands for democracy.

The Pearl Roundabout became a permanent encampment for the protesters. Tents were set up for families to rest in. Food stalls were teeming. A media center was operated by young Bahraini men and women. There was an exhilarating sense of freedom and of people standing up for their historic rights.

For the next three weeks, the Khalifa regime was on the ropes. The police and army were overwhelmed by the sheer number of protesters. At rallies there were easily 200,000-300,000 people at a time. For an island of only one million, there was a palpable sense that the long-oppressed majority had awakened to demand their historic rights against the imposter Khalifa regime. People were openly declaring, “the Republic of Bahrain”. This was a revolution.

In a lucky break, I was filing reports for the Irish Times and other Western media. The money was much appreciated, but more importantly there was an edifying, inspirational story to be told. A story about people overcoming tyranny and injustice.

All that would change horribly on March 14 when the Saudi and Emirati troops invaded Bahrain. The invasion had the support of the United States and Britain. What followed in the next few days was brutal repression and killing of peaceful protesters. The Pearl Roundabout was routed by indiscriminate state violence. Its sculpted monument was demolished to erase the “vile” memory of uprising. Men, women, medics, opposition thinkers and clerics were rounded up in mass detention centers. People were tortured and framed up in royal courts, sentenced to draconian prison terms. To this day, 10 years on, many of the Bahraini protest leaders – many of whom like Hassan Mushaimi and Abduljalil al-Singace I interviewed – remain languishing in jail.

However, a strange thing happened. Just when the story was becoming even more interesting – if not heinous – I found the Western media outlets were no longer open for reports. Some of my reports to the Irish Times on the repression were being heavily censored or even spiked. The editors back in Dublin were telling me that the news agenda was shifting to “bigger events” in Libya and Syria.

The corporate news media were shifting their focus to places where Western governments had a geopolitical agenda. Genuine journalistic principles and public interest didn’t matter. It was government agendas that mattered. The Irish Times and myriad other derivative media outlets were following the agenda set by the “majors” like the New York Times, CNN, the Guardian, the BBC and so on, who were in turn following the agendas set by their governments.

For Washington and London and other Western governments, the Arab Spring became an opportunity to foment regime change in Libya and Syria. The protests in those countries were orchestrated vehicles to oust leaders whom Western imperial states wanted rid off. Muammar Gaddafi in Libya was murdered in October 2011 by NATO-backed jihadists. Syrian President Bashar Al Assad nearly succumbed but in the end managed to defeat the Western covert war in his country thanks to the allied intervention of Russia and Iran.

All the while, the Western media were telling their consumers that Libya and Syria were witnessing pro-democracy movements, rather than the reality of NATO-sponsored covert aggression for regime change.

A person might be skeptical of claims that Western media are so pliable and propagandist. I know it for a fact because when I was reporting on the seismic events in Bahrain – which were truly about people bravely and peacefully fighting for democracy – the Western media closed their doors. They weren’t interested because there were “bigger events elsewhere”. Bahrain, like Yemen, would be ignored by the Western media because those countries didn’t serve the Western geopolitical objectives. Whereas Libya and Syria would receive saturation coverage, saturated that is with Western imperial propaganda.

Bahrain was and continues to be ignored by Western media because it is an integral part of the Saudi-led Gulf monarchial system which serves Washington and London’s imperial objectives of profiteering from oil, propping up the petrodollar and sustaining massive weapons sales. Democracy in Bahrain or in any other of the Gulf regimes would simply not be tolerated, not just by the despotic rulers therein but by their ultimate patrons in Washington and London.

I continued to report on the regime’s atrocities in Bahrain. My reports would be taken by alternative media sites like Global Research in Canada and indie radio talk shows in the United States. The money wasn’t great, but at least I could try to get the story out. In June 2011, four months after the Arab Spring began in Bahrain, the regime copped my critical reporting. I was summoned over a “visa irregularity” to the immigration department but instead was met by surly military police officers who told me I was “no longer welcome in the kingdom of Bahrain”. I was given 24 hours to leave “for my own safety”.

I returned to Ireland where after a few months I would relocate to Ethiopia in September 2011 to work as a freelance journalist for Global Research, initially. Later I began to work for Iran’s Press TV and Russian media. I first started working for this online journal, Strategic Culture Foundation, in late 2012. And my best move? I married an Ethiopian woman whom I had met in Bahrain during the Arab Spring.

Witnessing the struggle for democracy and justice in Bahrain was a privilege, one that I hardly expected or even wanted initially. But it fell to me. I witnessed such bravery and kindness among long-suffering Bahraini people who shared their grievances with generosity and graciousness despite the horror and oppression around them. Their struggle continues in spite of the lying, conniving Western governments and their media lackeys.