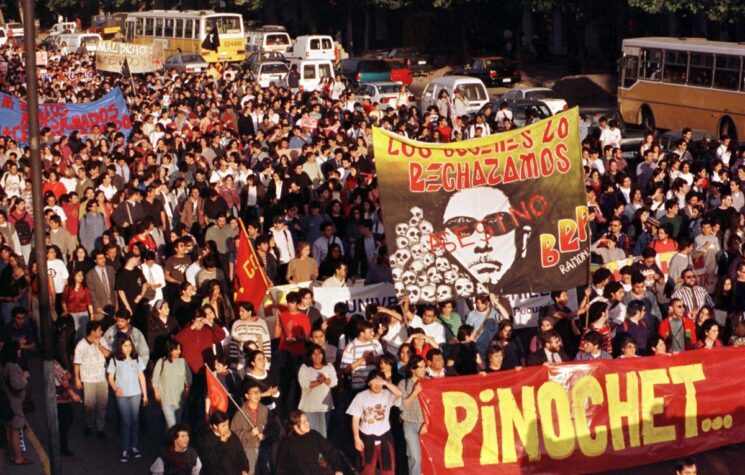

When Chile erupted in protests over the neoliberal politics of President Sebastian Pinera and the dictatorship legacy of Augusto Pinochet, the indigenous Mapuche population embarked upon the tearing down of colonial monuments and statues occupying Chilean public spaces. The news was of paramount importance for Chile’s reclamation of its historical memory, in particular as during the dictatorship, legal references to the Mapuche were removed.

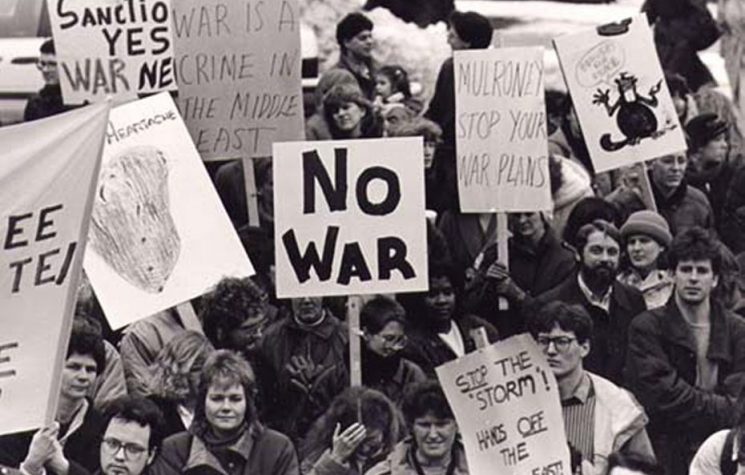

Elsewhere in the world, the Chilean struggle to preserve the people’s historical memory did not resonate so much. Now, as statues glorifying colonialism were toppled over and vandalised in the U.S., the UK and Belgium, the ramifications of colonial rule have been brought closer to home, in particular the links between colonialism and racism. The question that should be asked is what happens once the current protests simmer down and the current reckoning is no longer a news item and shielded from public scrutiny and interest?

There have been mixed reactions to the toppling and vandalising of colonial monuments, from approval of their elimination to the cloistering of such relics in museums. The current uproar necessitates a strategy, if the initial manifestations against historical colonial legacy are to bear any impact on current politics.

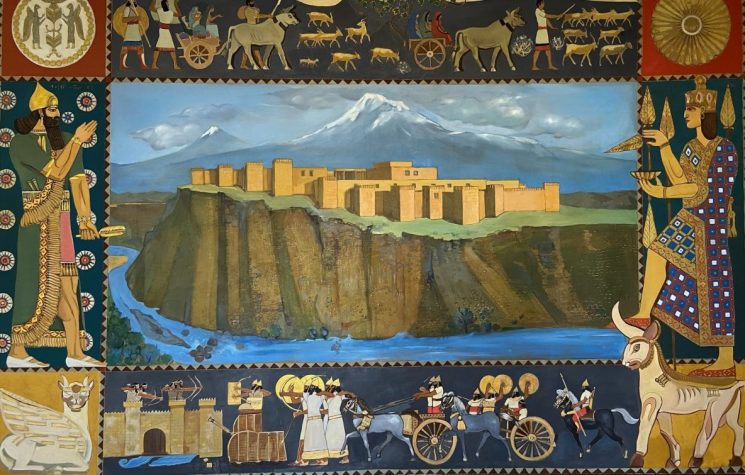

Glorification and eradication can both lead to different forms of oblivion in the absence of education. By colonising public spaces and having education systems perpetuate the colonial narrative, the collective historical memory which matters is marginalised to accommodate an ongoing violence which neglects the voices of the colonised. As Fidel Castro once declared in 1960 while addressing the UN General Assembly, “Colonies do not speak. Colonies are not known until they have the opportunity to express themselves.”

For the colonised, anti-colonial struggle is also a reclamation of narratives. The former colonial powers, or systems of governance built upon colonial legacies follow a different trajectory in reckoning with their past. For example, the differentiation between grudgingly made reparations to former colonies, and the glorification of colonialism through erected monuments within the public spaces of former colonisers, is proof of an existent political dissonance which requires more than temporary anger and destruction.

Belgium, for example, has followed up the demonstrations with the intent to set up parliamentary debates that go beyond “gratuitous apologies”. Reparations for Belgium’s colonial legacy in the Congo are expected to form part of a commission that is charged with establishing truth and reconciliation.

Land appropriation and exploitation, slave labour, trafficking, genocide, massacres and the maiming of the colonised populations are components of historical memory which should be brought to the fore, if the former colonial powers now styled as democratic countries are to alter thinking and politics beyond the visible memorabilia and monuments, or the preservation of colonial history in museums, as the fate of some removed statues will be. Preserving racism in museums is an established framework that can impede the current awareness from developing into anti-colonial recognition and solidarity. The repatriation of stolen artefacts and human remains to their respective indigenous communities are only part of the decolonisation framework.

The current focus on public spaces and how these are tainted by colonialism can become a historical act if, through education, society becomes attuned to decolonisation. To think critically about history, in particular to refute the mainstream narratives as absolute truth, should accompany the current furore over monuments, which risks becoming an isolated act if not substantiated by a rethinking of historical identity. In Europe, far from the ramifications of colonialism, this process is paramount. It requires a thorough reckoning with the past, one that brings the subaltern narratives to the helm. Anything less will merely reflect the hegemonic view on human rights and values – a concept which has obstructed an authentic process of decolonisation.