As coronavirus spreads in Latin America, indigenous peoples find themselves at imminent risk of annihilation should the pandemic break out in their communities. The Coordinator of Indigenous Organisations of the Amazon Basin (COICA) has written to the governments of countries which share the Amazon rainforest to enforce control on movement in and out of the indigenous territories, to help prevent a possible contagion.

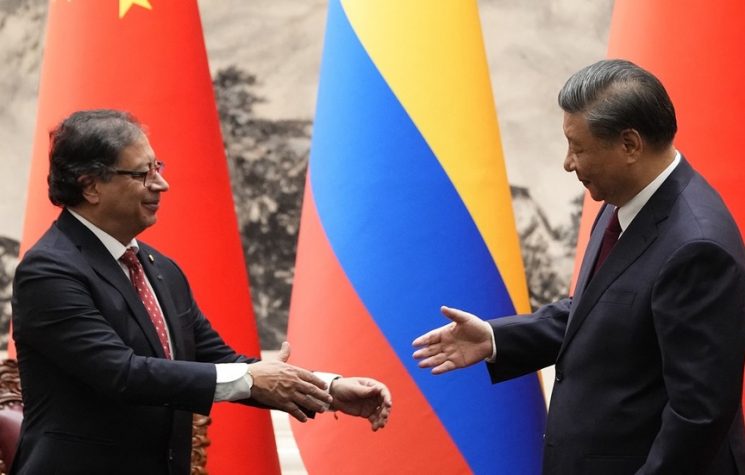

However, the virus spread is not the only danger for indigenous communities. In Colombia, unknown assailants killed two indigenous people and wounded two others. All victims were in their home observing quarantine. Far-right paramilitaries are suspected to have carried out the attack, with full impunity from the Colombian government due to its reluctance to investigate criminal activity and the targeting of the indigenous populations on their lands.

Indigenous representatives have asked the government to implement a ceasefire to regulate the precarious political situation. Failure to regulate hostilities would exacerbate the already violent conditions under which indigenous communities live, especially with the virus threat looming.

In Ecuador, the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of the Ecuadorean Amazon (CONFENAIE) closed access to the rainforest for non-indigenous people and companies, demanding a complete halt to industrial activity as a means to prevent the coronavirus from reaching their communities. Two cases of coronavirus – both tourists who visited the forest – have been confirmed, thus raising the alarm and a possible threat of extinction for indigenous people in the area.

Across Latin America, indigenous populations are emulating Ecuador’s approach, with communities taking the initiative to protect themselves by blocking access to their lands and staying on their territory. The action taken by indigenous communities is a form of resistance which governments have criminalised in the past within the context of multinational companies’ exploitation of land and natural resources. For indigenous communities, the current protection for their own well-being to prevent a coronavirus outbreak is also the means through which a statement can be made about land ownership which, in Brazil and Chile for example, will be in direct confrontation with the governments’ plans for industrialisation of the Amazon and the Araucania, respectively.

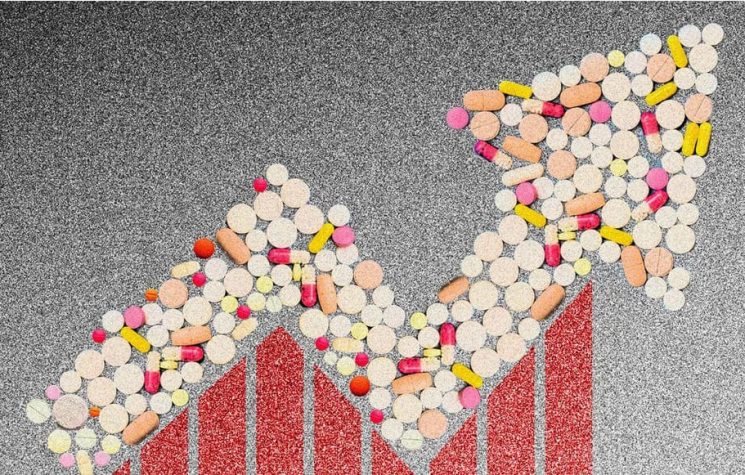

Brazil’s President Jair Bolsonaro has taken the coronavirus spread lightly, prioritising profit over health and refusing to set strict quarantine rules. The poor are suffering the most, rationalised the president who has squandered Brazil to neoliberal profits. Bolsonaro has also threatened to fire Health Minister Luis Henrique Mendetta after the latter emphasised the importance of quarantine and refused the president’s rhetoric that coronavirus could be treated with medication used for malaria.

Refuting pandemic evidence constitutes additional dangers to indigenous communities in Brazil’s Amazon. An indigenous woman from the Kokama tribe in Brazil’s Amazon has contracted the coronavirus, raising fears of the spread among the communities. If industries – notably mining and agribusiness companies – disregard quarantine which the president himself is not taking seriously, both the risk of contamination and the risk of violence against indigenous people will be heightened. Undoubtedly, the communities will be on alert for any disruption that could jeopardise their communities’ health. However, with the government offering no protection, it is possible that there will be an escalation of violence committed with complete impunity from the government.

The danger for indigenous communities and environmental activists is unlikely to drop in the coming months. Colombia is one example of exploiting the coronavirus pandemic to target indigenous people. For right-wing governments in the region, the pandemic presents an opportunity to combine two deadly weapons – a virus and state impunity – to criminalise and target indigenous communities and their activism. Always elusive, governments’ accountability in this period is likely to become even more inaccessible through state and multinational violence cooperation, if there is no complete cessation of incursions into indigenous terrain.