In Ecuador, the recent indigenous revolt against President Lenin Moreno’s neoliberal policies was instrumental in the repealing of a law which would have terminated fuel subsidies and plunged the most vulnerable into additional deprivation. The Ecuadorean government’s announcement, however, must not be misread as victory. It is the beginning of a long struggle which the people will face as Moreno maintains his commitment to the $4.2 billion loan from the International Monetary Fund, granted as he waived Julian Assange’s right to refuge at the Ecuadorean Embassy in London.

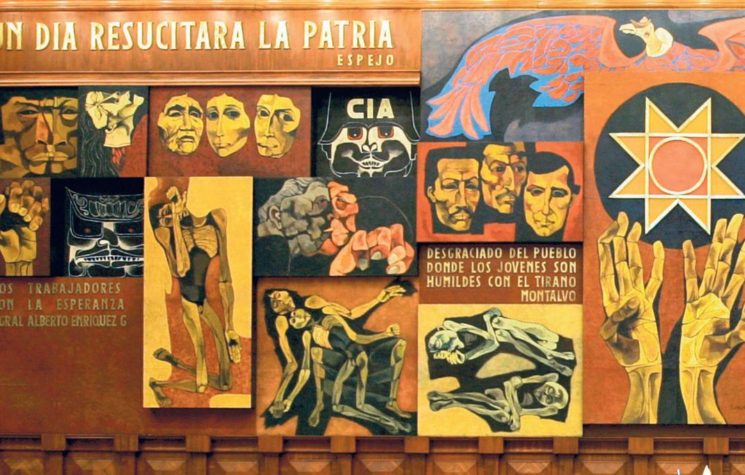

US influence at the IMF must not be underestimated. It owns 17.46 per cent of shares in the institution. Yet under the pretext of the institution being allegedly “governed by and accountable to the 189 countries that make up its near-global membership,” the US has another platform it can monopolise when it comes to foreign intervention tactics. Then, it can substantiate its IMF role with the country’s official foreign policy, as evidenced by US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s press statement over Ecuador’s violent repression of the recent protests: “The United States supports President Moreno and the Government of Ecuador’s efforts to institutionalise democratic practices and implement needed economic reforms.” In the words of Andres Arauz, a former Ecuadorean Central Bank official, “what the IMF does in Western hemisphere is US foreign policy.”

To safeguard his complicity with the US and the IMF, Moreno declared a national state of emergency, pitting the police and the military against Ecuador’s civilians. Thousands of protestors were met with state violence and an indigenous leader, Inocencio Tucumbi, was killed by government forces. An official statement brings the injured toll to 554 and 929 people were arrested. CONAIE President Jaime Vargas’s count of injured, killed, detained and disappeared, however, exceeds what has been reported by the government.

In typical dictatorial attitude, Moreno has inflicted several rounds of human rights violations upon the people: targeting the weakest sectors with price hikes due to the removal of subsidies and punishing rebellion with state repression to cement allegiance with the IMF. Within the international arena, where the IMF enjoys its privilege, any talk of preserving human rights is unlikely to make the correlation between Moreno’s violence and his monetary bondage as part of his neoliberal legacy.

The mobilisation at grassroots level by the indigenous communities and the workers is part of a wider historical context in Ecuador’s anti-neoliberal struggle. In the 1980s indigenous communities in Ecuador clamoured for land and cultural rights, while denouncing neoliberalism. The protests brought indigenous communities together as a unified voice and soon mobilised to demand bilingual education and agrarian reform, placing the indigenous at the helm of mass mobilisation. As a result, CONAIE established itself as a political party.

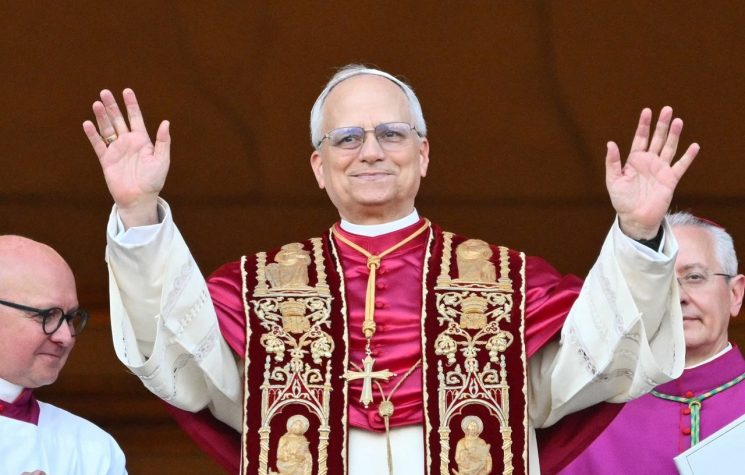

For now, the mobilisation at a national level has forced the government to repeal its initial declaration. According to the UN Representative in Ecuador Arnaud Peral, Moreno’s decree will be replaced by a new draft with the input of indigenous movements and the government, also with the input of the UN and the Catholic Church.

While celebrating this initial victory, caution is required. It is unlikely that the new bill will repudiate the onslaught of repercussions as a result of Moreno coercing Ecuador into IMF allegiance. For the time being, Latin America is indeed in the clutches of right-wing leadership. Yet the people are facing similar struggles and the possibilities for regional unity are endless. This accelerated phase of neoliberal exploitation, in Ecuador and elsewhere, is igniting a movement which is taking the struggle right to its roots – to the people. Moreno will not back down from his policies, yet the people of Ecuador have equally displayed their resilience.