There is sudden rush by countries for island real estate. Some of this “island fever” is driven by global climate change. Some countries are looking for strategic advantages in a new geo-political order, one where American influence has drastically ebbed.

While Donald Trump shocked the world by admitting that he is entertaining purchasing the world’s largest island, Greenland, from Denmark, regardless of the fact that it is not for sale, there are other island moves taking place in the Middle East, Indian Ocean, South Pacific, and elsewhere. What makes Trump’s obsession unique is that Trump appears to think that an island like Greenland that is under duress from global warming is prime for a hostile takeover bid. While that may be a business strategy in Trump’s cut-throat world of high-end real estate, it is not acceptable in the world of diplomacy and international relations.

When a Manhattan hotel is sold, the purchase agreement does not include all of the hotel’s occupants. Greenland’s population is 57,000, 88 percent of whom are native Inuit. There is little chance that the Inuit citizens of Greenland would want to become part of a country whose president repeatedly calls a US senator “Pocahontas” and disparages the treaty rights of Native American tribal nations. Nor would the Inuit, as well as the ethnic Danish minority, want to sacrifice their top-notch national health care system for one of the worst in the industrialized world.

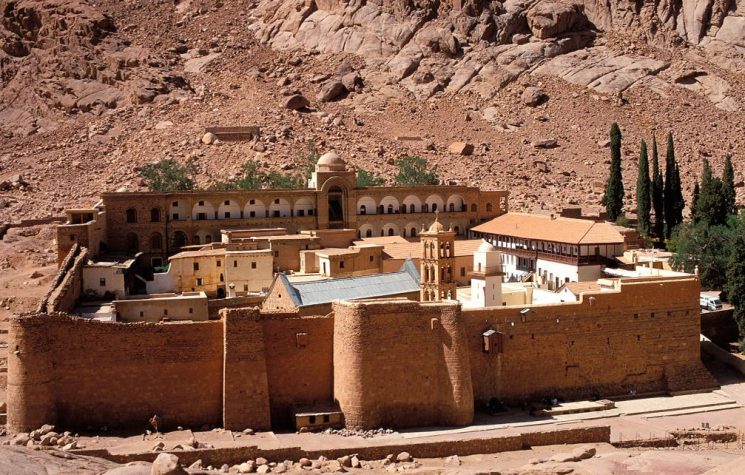

Another strategic island, Socotra, which lies in an important shipping channel in the Gulf of Aden, is currently a highly-contested prize between the United Arab Emirates, the internationally-recognized government of the Yemen Arab Republic – exiled in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, the South Yemeni secessionist Southern Transition Council (STC) – which is backed by the UAE and seeks restoral of South Yemen’s former independent status, and the British colonial era Mahra State of Qishn and Socotra, which is supported by Oman, where the pretender to the throne of Qishn and Socotra, Sheikh Abdullah Al Afrar, is headquartered when he is not present in Socotra. Socotrans have grown tired of the presence of Emirati and Saudi troops on their pristine island, called the “Galapagos of the Indian Ocean” due to the presence of flora and fauna not found anywhere else in the world. During the final 75 years of the Mahra State, the Mahra sultans ruled their British protectorate from Hadiboh, the capital city of Socotra.

There are significant historical links between the Mahra and Omani sultans and Omani Sultan Qaboos bin Said has avoided participation in the Saudi-led coalition that is battling Houthi-led rebels who have taken control of much of North Yemen. The UAE, which took over control of Socotra’s airport and seaport, views Socotra as a key link between the UAE, the Horn of Africa, and the Red Sea. There has been some talk of the UAE leasing Socotra for 99 years. However, just as Greenland and Denmark have told Washington that Greenland is not for sale, the Socotrans and Mahra State, backed by Oman, have told Abu Dhabi that Socotra is not for lease.

To the south in the Indian Ocean, the UN General Assembly voted on May 22, 2019 to set a six-month deadline for the United Kingdom to withdraw from the Chagos Archipelago, which is claimed by Mauritius. In 1967, the British expelled the native Chagossians from the archipelago to make way for a major US military base on Diego Garcia. Mauritius, which became home to many Chagossian refugees, wants the original inhabitants resettled on their islands. London and Washington are balking at any such notion.

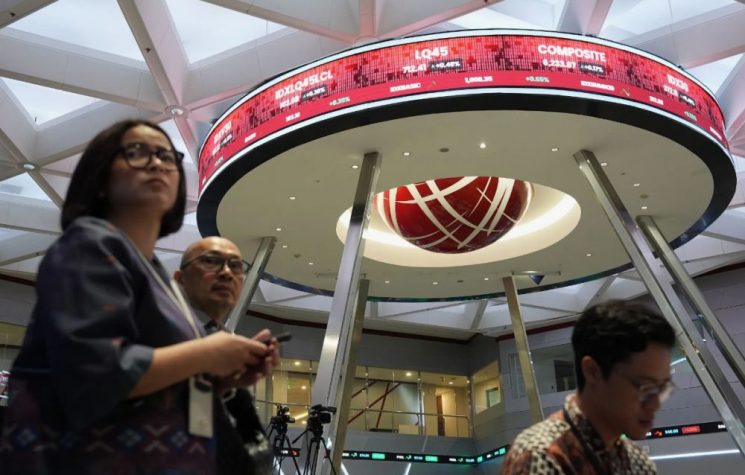

While Borneo, the world’s third largest island after Greenland and New Guinea, is part of Indonesia, the announcement by Indonesian President Joko Widodo that Indonesia will move its capital city from Jakarta to the northeastern part of Borneo will forever change the nature of Borneo. Half of Jakarta is currently below sea-level, a situation that has been caused by a combination of depletion of ground water and rising sea levels due to climate change. Current plans are to move Indonesia’s capital to a forested area between the East Kalimantan province cities of Balikpapan and Samarinda.

The new capital will be close to Eastern Malaysia’s states of Sabah and Sarawak and the Sultanate of Brunei. Like the Amazon Basin, East Kalimantan province’s rain forests have also earned it the title of “lungs of the world.” Environmentalists are concerned about the effect the new capital city will have on forest destruction, an issue that currently plagues the Malaysian state of Sarawak. Borneo is home to three secessionist movements. The Kalimantan Dayaks and Malays favor independence or unification with Malaysia. However, there are also nascent secessionist movements in Sarawak and Sabah that seek a complete break with Peninsular Malaysia. It remains to be seen how Indonesia’s new capital will be viewed by Kalimantan secessionists.

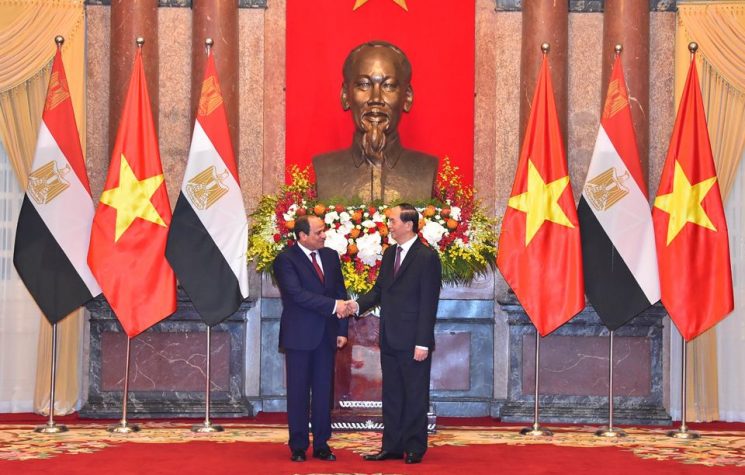

Two uninhabited islands in the Red Sea between Saudi Arabia and Egypt, Tiran and Sanafir, have been the subject of a virtual tug-of-war between the Saudis and Egyptians. In 2016, Egyptian President Abdel-Fattah El-Sisi said during a press conference with visiting Saudi King Salman, that the two islands would be transferred to Saudi Arabia. The Saudis insisted that they only temporarily transferred administration of Tiran and Sanafir to Egypt in 1950 in order to protect the islands from being occupied by Israel. In 1956, Israel did occupy the islands, but they were transferred back to Egypt following the 1978 Camp David accord between Israel and Egypt.

In response to the transfer of the islands, Egyptian protesters demanded that the Egyptian government not go through with the deal because it violated the terms of the Egyptian Constitution, which requires a national referendum is required before any change to Egypt’s borders. The Saudis plan to build a causeway via the two islands linking Saudi Arabia to Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula. Many Egyptians are keenly aware that the Saudi military crossed the Saudi causeway with Bahrain to help brutally put down a popular revolt by Bahraini citizens. They fear the same will occur with the Saudi causeway to Egypt.

Global climate change also resulted in one government, that of the rising sea level threatened South Pacific nation of Kiribati, to purchase land on the Fijian island of Vanua Levu that in the future would become the home to Kiribati’s climate change refugees and become an ex-situ seat of government for Kiribati. The 6,000 acres bought in 2014 by Kiribati’s then-president, Anote Tong, was seen as a model for how other threatened nations, including Tuvalu, Nauru, and Maldives, might maintain their identity and independence long after they disappeared beneath the waves. Tong called the project “migration with dignity.” Tong’s successor, Taneti Mamau, changed Tong’s plans. Rather than move to higher ground on Vanua Levu, Mamau now favors dealing with climate change effects in Kiribati. He said he favors leaving the future of Kiribati and the I-Kiribati people in God’s hands. That comes as little comfort to the people of the crowded Kiribati capital in South Tarawa, Abaiang, and other islands dealing with the effects of saltwater contamination of fresh ground water, ruined crops, and inundated houses.

From Washington and Jakarta to Copenhagen and Abu Dhabi island fever has taken hold with new real estate development plans at the forefront of major political and financial decisions.