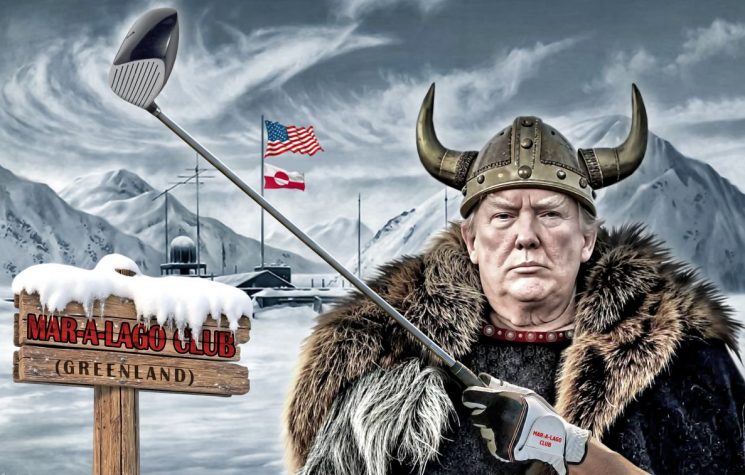

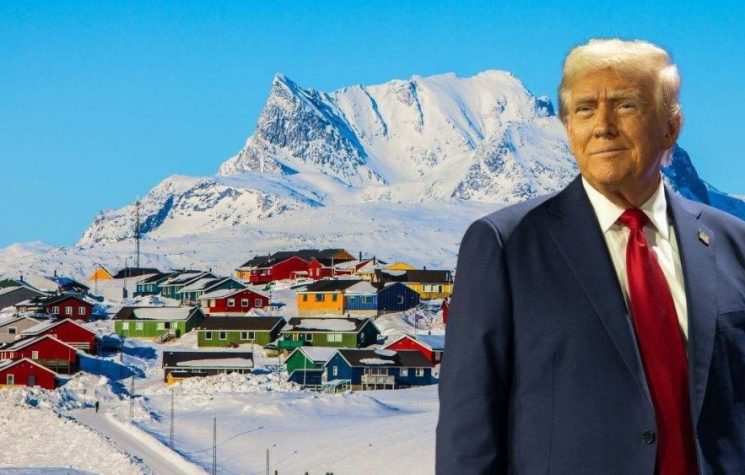

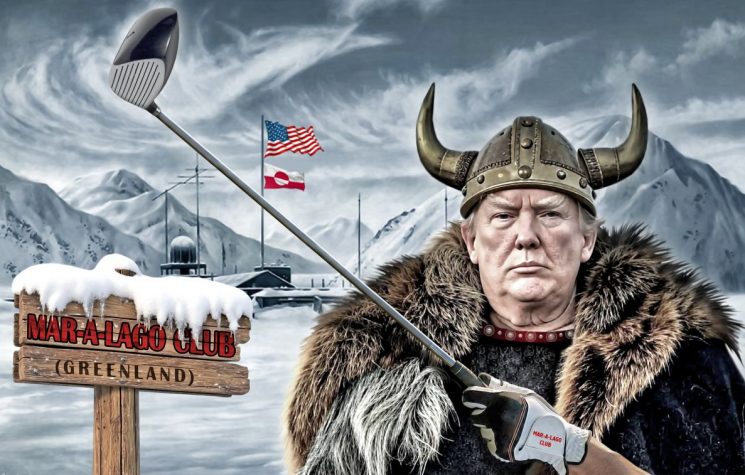

Following the U.S. attack on Venezuela, President Donald Trump’s renewed threats over Greenland have also triggered a crisis between Nuuk and Copenhagen.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

Following the U.S. attack on Venezuela, President Donald Trump’s renewed threats over Greenland have also triggered a crisis between Nuuk and Copenhagen.

It has emerged that Greenlandic and Danish officials clashed during a meeting held via the Microsoft Teams application.

Greenland, an autonomous territory within the Kingdom of Denmark, has a parliament known as Inatsisartut and a government referred to as Naalakkersuisut. Under the Self-Government Act that entered into force in 2009, areas such as education, healthcare, natural resources, and local administration are governed by Nuuk, while foreign policy, defense, and monetary policy constitutionally remain under Copenhagen’s authority. Although the vast majority of Greenland’s population is Inuit and the territory remains economically dependent on an annual block grant from Denmark, its rich underground resources and strategic position in the Arctic have frequently placed it at the center of international competition.

Continuous colonialism over Greenland

In fact, Greenland is, in other words, a modernized colony of Denmark. Beginning in 1261 via Norway and definitively falling under Danish sovereignty in 1814, the territory has been subjected to uninterrupted colonialism despite multiple changes in its formal status.

Although it was removed from its “colonial” status in 1953 and declared an “integral part of the Kingdom,” the forced displacement of Inuit communities on the island in pursuit of U.S. strategic interests during the Cold War; the insertion of contraceptive spirals into Inuit women without their consent under the guise of “birth control” until the 1970s; the systematic marginalization of the Greenlandic language and culture; the separation of children from their families; and the “regulation” of natural resources for Denmark’s benefit all clearly demonstrate that this process amounted to little more than a transformation in the form of an imperial relationship from Greenland’s perspective.

Therefore, both the United States setting its sights on the region and the tensions with Denmark are viewed by Greenlanders through the lens of a social memory shaped by long-term colonialism.

Heated dispute along the Denmark–Greenland line

For precisely this reason, the Teams meeting between Greenlandic and Danish officials turned into a scene of fierce arguments, with Denmark accused of displaying a “new colonial” attitude and the Greenlandic side charged with “irresponsibility.”

Moreover, according to Danish media, some participants expressed concern that Americans might have been listening in on the meeting.

The controversial meeting was held two days ago. Danish and Greenlandic politicians logged into their screens for an emergency Teams meeting convened to discuss the growing U.S. pressure on Denmark.

According to an exclusive report by political analysts Rikke Gjøl Mansø, Rasmus Bøttcher, Mette Pabst, and Cecilie Kallestrup published by Denmark’s public broadcaster DR (Danmarks Radio), voices were raised during the meeting, tempers flared, and some messages were even written “in capital letters.”

The meeting was organized by Christian Friis Bach, Chair of the Danish Parliament’s Foreign Policy Committee. Although Bach stated that the aim was to “enable elected Danish and Greenlandic representatives to share the information they possess,” several Greenlandic participants were already angry before the meeting even began.

One of them was Pipaluk Lynge, Chair of Greenland’s Foreign and Security Policy Committee and a member of the ruling party Inuit Ataqatigiit (IA). Lynge was reportedly extremely agitated throughout the meeting. The reason was that Greenland had not been invited to another emergency meeting scheduled for 6:00 p.m. that same day.

IA, a left-wing, socialist, and environmentalist party, follows an ideological line that is anti-colonial, centers Indigenous rights, and advocates Greenland’s long-term independence from Denmark.

“A new colonial method”

The other meeting from which Greenland had been excluded was held in the Danish Parliament under the title “The Kingdom’s relations with the United States.” Ahead of the meeting, Lynge voiced her reaction in the following terms:

“A historic meeting is being held about us, and yet we are not there. Being forced to sit in Greenland and demand participation in such an extraordinary meeting is extremely frustrating. This is a new colonial method that excludes us.”

Lynge’s anger only grew once the meeting began. Several participants told DR that she was pacing nervously around the room. When she took the floor, she accused Denmark of violating the principle of including Greenlanders in processes concerning Greenland.

Some members also reminded participants that high-security meetings require physical attendance, pointing to potential security risks.

“I’m tired of being treated like an idiot”

In a separate verbal confrontation with Danish “green-left” MP Karsten Hønge, Lynge is reported to have said, “I’m tired of being treated like an idiot.”

What particularly angered the Danish side during the meeting was the Greenlandic proposal to establish “direct contact with the United States” without Denmark.

Such a move would contradict the Danish Constitution, which stipulates that foreign policy on behalf of the Kingdom is conducted by the Danish government. For this reason, it is not possible for Greenland’s foreign minister to hold official talks with U.S. officials without their Danish counterpart.

“We don’t have to hold hands with Danish ministers when talking to other countries”

However, Juno Berthelsen of Naleraq, Greenland’s nationalist and pro-independence opposition party, confirmed that Greenlandic parliamentarians had proposed a “dialogue visit” to the United States:

“We want to establish direct contact with U.S. politicians—to hear what they think and to explain what we want for Greenland.”

This stance is hardly surprising. Naleraq advocates a rapid severing of ties with Denmark in the political sphere, independent action in foreign policy, and an end to Copenhagen’s “paternalistic” role. Economically, it emphasizes resource-based national development over the welfare state and calls for a swift end to dependence on block grants. In short, Greenland’s nationalist opposition argues: “Only we can negotiate our own resources.”

“We don’t have to hold hands with Danish ministers when talking to other countries”

What is more surprising is that this view was defended not only by Naleraq, but also by Lynge from the ruling party:

“We are adults in Greenland. We have a parliament, we have ministers. We don’t have to hold hands with Danish ministers when talking to other countries.”

The meeting ended without results

The meeting, initially scheduled to last one hour, was extended due to the arguments, and as it dragged on, Danish MPs began leaving one by one. Eventually, when only the two committee chairs—Christian Friis Bach and Pipaluk Lynge—remained, Bach invited his counterpart to a separate bilateral discussion.

Lynge declined, saying, “I will spend time with my children.”

The meeting had been expected to be the first critical gathering following Trump’s threats. Instead, its significance lay less in the steps to be taken against the United States than in once again exposing the political crisis along the Denmark–Greenland line.

Although discussions on Greenland often focus on U.S. intentions toward the region, the success of Washington’s plans depends not only on Trump’s “audacity” but also on the willingness of the region’s stakeholders to stand together. According to Greenlanders, however, the “condescending” attitude inherited from the colonial era among Danish officials continues to politically “push” Greenland away.

As U.S. pressure and threats toward the region intensify, it appears increasingly likely that a socio-political current will gain strength in Greenland—one that combines opposition to the United States with dissatisfaction toward the existing “Europe-centered” political climate, much as is occurring across the rest of Europe today, albeit with varying intensity.