Recent, well-documented events — though conspicuously underreported by the global media apparatus — offer a striking illustration of how this zoological logic operates in practice.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

Menachem Begin, Nobel Peace Prize laureate and prime minister of Israel between 1977 and 1983, is still widely presented as a statesman who helped secure peace in the Middle East. Less frequently recalled is his earlier career as leader of the Irgun, a Zionist terrorist organisation, and his political apprenticeship within paramilitary networks that once found shelter under Mussolini’s fascist umbrella. Begin was also fond of blunt formulations. Among them, one has echoed down the decades with chilling clarity: “Palestinians are animals who walk on two legs.”

That phrase was not an aberration. It belongs to a long ideological lineage. Zionism, as a doctrine combining ethnic supremacy, theological exceptionalism and colonial entitlement, has repeatedly relied on zoological metaphors to demarcate hierarchy. The “chosen people” are elevated above the rest of humanity, which is conveniently compressed into a lesser category of beings — goyim, foreigners, outsiders, expendable lives. Ovadia Yosef, former Israeli minister and founder of the Shas party, once expressed this worldview with brutal frankness: “The goyim were born to serve us. If not, they have no place in the world.”

Against this backdrop, the more recent language of Israeli leaders appears less like rhetorical excess and more like doctrinal continuity. When Defence Minister Yoav Gallant announced that in Gaza “we are fighting human animals and acting accordingly”, he was not improvising. Nor was former prime minister Naftali Bennett when he told Palestinian negotiators that “while you were still climbing trees, we already had a state”. These statements are not slips of the tongue. They are the vernacular of a civilisation that defines itself through exclusion, hierarchy and contempt.

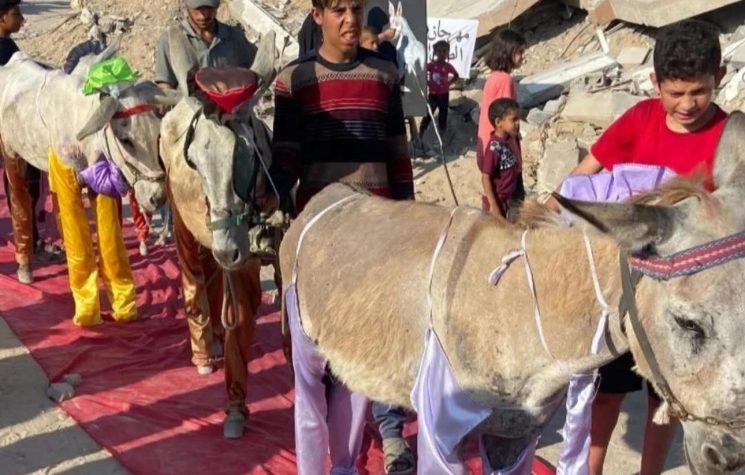

Recent, well-documented events — though conspicuously underreported by the global media apparatus — offer a striking illustration of how this zoological logic operates in practice. They reveal that, in the eyes of the Israeli state and its armed forces, not all animals are equal. There is, it seems, a decisive moral distinction between those who walk on two legs and those who walk on four — and it is the latter who enjoy the benefit of compassion.

Over the past months, hundreds of donkeys have been removed from the Gaza Strip by Israeli troops, particularly from areas still occupied following the latest, widely theatricalised “ceasefire”. These animals have been transported with notable care and tenderness to facilities inside Israel run by an organisation called Starting Over Sanctuary (SOS), located south of Tel Aviv. From there, many have been airlifted to Europe — chiefly to Belgium, France and Germany — where they are received as victims of war, trauma and abuse.

The story has been proudly told by Israel’s public broadcaster KAN and echoed by European outlets such as Germany’s Allgemeine Zeitung and the website Jewish News, often wrapped in emotionally charged language celebrating empathy, humanity and moral responsibility.

According to SOS, the donkeys undergo treatment for “psychological trauma” upon arrival, having allegedly suffered from “disease and neglect” in Gaza. Since 7 October 2023, the organisation claims to have sheltered some 1,200 animals, saving them from bombardment and from what it delicately describes as the harsh realities of war.

Other sources, less inclined to lyrical framing, note that since that same date — 7 October 2023 — roughly 70,000 Palestinians have been killed in Gaza, around a third of them children. But these deaths belong to a different category of life. These are the “two-legged animals” Begin spoke of; or, as Israeli writer Moshe Smilansky once put it, “a semi-savage people with extremely primitive concepts”. Statistics, meanwhile, remain silent on how many donkeys may have perished under Israeli fire.

Europe, always keen to advertise its commitment to human rights — and, in this instance, donkey rights — has assumed an active role in this rescue effort. In May 2025, 58 donkeys were flown from Israel to Liège airport in Belgium, rested overnight, and then transported onward to sanctuaries in Belgium and in France, near Chartres. Upon arrival, they were celebrated publicly as “symbols of compassion and civility”.

The British organisation Network for Animals, which coordinated the logistics, assured the public that the animals — described as victims of “war and abuse” — experienced a “stress-free transition”. During those same days, Israeli forces killed approximately 2,000 Palestinians in Gaza.

In Germany, four donkeys — Anna, Greta, Elsa and Rudi — were welcomed near the town of Oppenheim after passing through the Israeli sanctuary. They were provided with climate-controlled stables to ease their adjustment from the heat of Gaza to the cooler European climate and given time and space to recover from “psychological stress”.

Only weeks earlier, the German government had refused to admit around 20 Palestinian children severely wounded in Gaza for medical treatment. By contrast, any Israeli citizen wishing to remain in Germany is granted immediate hospitality and legal protection.

This cooperation between Israel and EU member states in rescuing donkeys from Gaza — and the West Bank — is presented as a natural expression of shared humanist values. After all, as Benjamin Netanyahu repeatedly insists, Israel represents “our civilisation” in a region allegedly overrun by barbarians.

Former EU foreign policy chief Josep Borrell echoed the same imagery when he warned that Europe’s “garden” of civilisation is increasingly threatened by barbarian forces from beyond its borders. Israel, in this narrative, stands as a frontline bastion — defending the garden, even enriching it with rescued donkeys fleeing the savagery supposedly embedded in barbarian blood.

What remains largely unmentioned is that these animals are being taken from their rightful owners. In Gaza, now reduced to something resembling a vast open-air concentration camp, donkeys have become indispensable. With agriculture destroyed, infrastructure obliterated and fuel scarce, they are often the only means of transporting people, food, water and belongings. They accompany families during forced displacements, long marches and repeated internal exoduses imposed by Israeli military operations.

To confiscate these animals under the pretext of rescue is not only an act of theft — it is a calculated cruelty that further undermines the population’s capacity to survive. Under international law, the seizure of property from an occupied population constitutes a war crime. But such legal “antiquities” rarely trouble the conscience of those who define themselves as civilisation’s guardians.

It has not yet been reported — though one suspects it is only a matter of time — that Portugal, under the watchful eyes of Ventura and Montenegro, may prepare facilities to welcome its share of Gaza’s rescued donkeys. After all, these are model immigrants: harmless, compliant, politically silent. They require no work permits, pose no cultural challenge, and bray only when they have reason — a perfectly legitimate expression of opinion.

Unlike human refugees, they carry no inconvenient memories, no grievances, no demands for justice. They fit neatly into the moral economy of a civilisation that prefers compassion without consequence, empathy without accountability, and humanitarianism safely detached from human suffering.

One detail, however, stubbornly persists. Amid the rubble, the corpses and the silence, the braying grows louder. And when “our civilisation” brays, it is not always clear whether the sound comes from the donkeys — or from those who claim to have rescued them.