The Cold War experience suggests that stabilizing even an intense rivalry is possible if both sides perceive such a process as important or vital to broader interests.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

Competition issues

The competition between the United States and China is not the first major rivalry between powers to raise the issue of how to stabilize potentially dangerous dynamics. In the modern history of international relations—leaving aside previous eras—the great powers, both in Europe and Asia, have repeatedly sought to give a stable form to their competitions, while continuing to pursue relative advantages. With the exception of a few revisionist or predatory states with no restraints whatsoever, most powers have understood that their interests were best served by mechanisms of containment and moderation. It is therefore useful to place the possibility of a stable balance in the Sino-American rivalry within a broader historical framework.

To better understand U.S. competition with China, let us consider coexistence within rivalry—defined by some contemporary scholars as “managed competition” or “competitive coexistence”—from a historical perspective. The goal is twofold: on the one hand, to grasp the historical precedents for such attempts; on the other, to define the concept itself more precisely, in order to better understand what is meant to be promoted in the relationship between Washington and Beijing, in a more limited sense than more ambitious agendas that aim for a general type of coexistence.

Surprisingly, many fundamental concepts related to the dynamics of international competition, including commonly used terms such as “competition,” are often poorly defined or insufficiently conceptualized in the literature on world relations. The concept of “rivalry,” on the other hand, seems clearer: it refers to a situation in which two or more major powers of approximately equal strength perceive each other as hostile and deeply distrustful; they carry with them a history of conflict and confrontation, harboring expectations of further tensions in the future; and they maintain opposing, sometimes irreconcilable, positions on important political issues. Many of these rivalries, however, do not lead to total war, but most of them come to an end sooner or later, and almost all of them involve some form of conscious moderation: attempts to introduce elements of stability and restraint into a competition that, while remaining fierce, recognizes the need for certain shared rules of conduct. These efforts can take different forms.

On the concept of coexistence

One of the most common interpretations of the concept of coexistence suggests that it occurs when the great powers succeed to a large extent in transcending their rivalry and establishing a new type of relationship based on trust, respect, and sometimes even alliance. This explains why, in the current context, some observers are wary of the idea of coexistence between the United States and China: in its most traditional sense, the term implies the end of competition, a goal that seems unlikely in the short term. During the Cold War, several analysts attempted to break down the concept of coexistence to make it more realistic, particularly in the late stages of the confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union.

At the end of the Cold War, a sort of common theory regarding coexistence between East and West was theorized. The need was obvious: the logic and behavior of the Cold War—exaggerated threats, high levels of armament, internal discipline within the blocs, and the systematic construction of the enemy—were now inadequate in an increasingly interdependent world. A conscious effort to stabilize East-West relations was therefore needed.

To achieve this, a first step would have to consist of a decade of ‘constructive engagement’, during which the two sides would define mutual rules of interaction to guarantee their respective interests and create a minimum of trust in each other’s intentions and behaviour. This phase would require agreements on thorny issues, such as the future status of Germany and Eastern Europe, accompanied by symbolic gestures of respect and cooperation. The ultimate goal of this initial stage was to achieve a predictable and mature relationship of “constructive détente.”

This would be followed by a period of about fifteen years devoted to building a “legitimate international order,” supported by formal agreements and institutions modeled on the Concert of Europe, in which each great power would see its fundamental interests guaranteed and all could coexist as status quo powers. The international order is achieved when nations accept common rules of behavior and agree on the practical modalities of their implementation.

With trust consolidated and cooperative institutions now stable, the two sides could have reached a third stage: that of “stable peace,” a condition in which war becomes unthinkable not because of fear of mutual destruction, but because of shared satisfaction with the existing situation. A peace, therefore, based on political relations and not on cosmic fear.

It is also plausible that rivalries can evolve into genuine geopolitical partnerships through a process that political scientist Charles Kupchan framed in four stages: accommodation, mutual restraint, social integration between the two societies, and the development of new narratives and shared identities. In rare cases, such as in the post-war European process, these dynamics have led to the creation of deep cooperative institutions. However, such results remain fragile and reversible: Kupchan himself points out that progress towards stable peace is never guaranteed, and that a return to hostility is possible, if not frequent.

Other scholars have identified the conditions necessary for a rivalry to end. Rasler, Thompson, and Ganguly argue that rivalries diminish or end when adversaries develop new interpretations and expectations of each other, a process that requires favorable circumstances and risk-taking leadership. Kupchan, analyzing historical cases of rivalries being overcome, concludes that such an evolution is only possible when both sides have political systems capable of containing excessive ambitions, when their social and economic structures do not pursue zero-sum goals, and when there is at least a partial cultural commonality. It is clear that these conditions do not exist today in the relationship between the United States and China.

Declining stability

These examples show that the realistic goal for Sino-American relations is not full coexistence or the end of rivalry, but a more modest yet essential step: identifying a stable modus vivendi based on specific agreements and a balance that reduces the risk of crisis, leaving room for limited but meaningful forms of cooperation. For the U.S., this essentially means learning to coexist without assuming a relationship of friendship or deep trust. But is this really the case?

The origins of the notion of coexistence in Soviet doctrine offer an example of this limited but pragmatic view of stability. In the Soviet conception, “peaceful coexistence” did not imply a genuine acceptance of capitalism, but rather a temporary truce, during which the historical dynamics of Marxism would continue to erode the capitalist system. For Lenin, for example, coexistence should have remained competitive, since the socialist state had the task of demonstrating, by example, the superiority of its economic and social system.

Yet Lenin and other Soviet leaders recognized that this phase of stability could last for decades, making extensive economic cooperation and a certain degree of pacification possible. Soviet doctrine, while remaining ideologically hostile to capitalism, thus acknowledged the need for a minimal form of ‘coexistence’. This pragmatic and patient approach would later justify, during the period of détente, further delays in the prospect of the final victory of socialism.

In 1985, Adam Ulam recalled how the long history of conflict and hostility between East and West had made that rivalry particularly bitter, but also how, in the 1970s, there had been a growing awareness of the dangers of uncontrolled confrontation. The 1968 nuclear non-proliferation agreement was the most obvious proof of this.

As early as the 19th century, the Concert of Europe represented a middle ground between rivalry and cooperation. After the Napoleonic Wars, the great European powers, and in particular the dominant monarchies, shared a common interest in stability and the defense of the conservative order. The enormous destruction caused by those conflicts—over four million deaths—had created an imperative for containment. The Concert gave rise to a system of consultation and crisis management that partially transformed the rules of European diplomacy, creating a sort of embryonic security community. Yet these accommodations were temporary as rivalries resurfaced, first in colonial disputes, then with the Crimean War, and finally with the devastating world wars.

Revival of deterrence

The best-known and most modern version of stabilized competition between great powers was the détente during the Cold War, between 1968 and 1979. This period, often misunderstood or mythologized, was in fact a pragmatic attempt to regulate a rivalry that had become too costly and dangerous. Détente arose from the recognition, shared in Washington, Moscow, and to some extent also in Bonn with the Ostpolitik, that totally unregulated competition threatened the very survival of the powers involved.

U.S. and Soviet leaders accepted two key elements of stable competition: the definition of a certain status quo through arms control regimes, and the creation of personal and institutional ties for crisis management (). Détente was the expression of this awareness. Contrary to what some critics have argued, this was not a Soviet ploy to deceive the U.S., but rather a mutual attempt to keep competition within manageable limits. This required both formal agreements and sufficient personal trust to deal with inevitable crises.

Détente, as a political approach, was not exclusive to that decade, but became a kind of experiment in international relations. Throughout this period, U.S. policy maintained an essential distinction between overcoming rivalry and building a regulated modus vivendi that would allow competition to continue within controlled margins. The goal of détente was not to eliminate the Soviet threat, but to manage it in a way that reduced costs and prevented destructive crises.

It is therefore not surprising that, if interpreted as an attempt to end the Cold War, détente appears to have been a failure; but if it is seen as an attempt to stabilize inevitable competition, it was a partial success. Its architects had always intended it as an intermediate measure: a source of balance, not reconciliation. The United States continued to compete with the USSR during that period, while the Soviet Union sought to consolidate its position in Europe as a superpower promoting peace and integration.

However, the process could not really benefit the Soviet Union in any significant way. Détente and accommodation could not save a system that was already in crisis, partly because access to Western technology “often failed due to problems with the Soviet state planning system. Meanwhile, opening up to the outside world undermined official Soviet claims about the superiority of their system, allowing more citizens to travel and access Western information and entertainment. The opportunities offered by détente exposed the Soviet people to alternative ways of life, eroding the myth of Soviet exceptionalism. For a government that based its legitimacy on protecting Soviet citizens from a rapacious capitalist world, tempering ideological confrontation reduced the legitimizing effect of an irrevocable clash. In short, the process of détente greatly accelerated the process of internal degeneration and self-destruction of the Soviet ‘socialist’ project.

Détente was a mistake for another reason as well, arguing that Reagan’s abandonment of the concept in favor of tough confrontation was what ultimately shattered the Soviet system and led to victory. This perspective implies that great powers, in order to achieve true success in rivalries, should not seek coexistence, but rather destabilize their rival. This, too, is a simplified reading of the Cold War. First, Reagan’s approach always combined pressure with the offer of a transformed relationship, provided that the USSR mitigated some of its most problematic behaviors. Reagan certainly took many aggressive actions to compete with the Soviet Union, but at the same time, he pursued a long series of steps aimed at stabilizing the relationship.

Reagan aimed to transform the rivalry into something more peaceful, based on Soviet behavioral change, but with a vision that could be described as enhanced détente. He continually offered this perspective to one Soviet leader after another. When Gorbachev came to power, Reagan maintained pressure but overcame his more bellicose advisers and moved toward a strategy more nuanced than simple coexistence.

This experience also highlights the importance of maintaining commitment to core interests and values while adopting stabilization measures. Throughout the period from Nixon to Reagan’s interaction with Gorbachev, the United States remained firm on issues it considered vital, confirmed commitments to allies, and, in specific crises, faced the risk of conflict. Even during periods of détente, they confronted the USSR in 1973, made threats of escalation in Vietnam, significantly increased military capabilities, and confronted Soviet threats related to Euromissile missiles.

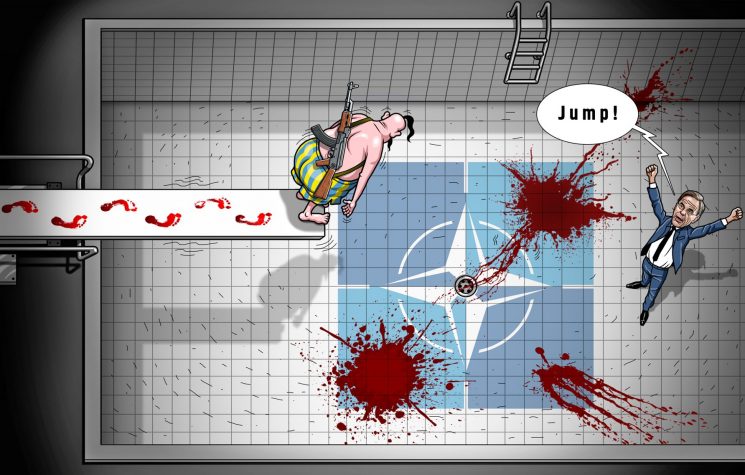

This experience offers relevant lessons for the U.S.-China rivalry: it suggests that stabilizing even an intense rivalry is possible if both sides perceive such a process as important or vital to broader interests. It also indicates that moderating a rivalry can serve U.S. interests if it helps prevent crises and conflicts and allows for the development of deeper strategic advantages.

Stabilizing a rivalry can make the underlying dynamics visible, to the advantage of the side with a more sustainable, persuasive, and attractive model. Any scenario of stabilized rivalry will have to include different goals. And such rivalry will not end with a complete systemic victory for the United States as in the Cold War: long-term effective competition is more likely, until the U.S. exhausts its war reserves and is forced to deal with the last gasps of a declining imperialism.

This is the real lesson of détente in the Cold War and, more generally, of many other phases of coexistence between great powers: efforts to mitigate the most dangerous forms of competition are essential to pursuing both modest and ambitious goals in any rivalry.