Brilliant Eurasian cultures converged, interacted and spread their wings on the Ancient Silk Roads.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

DUNHUANG – Across History, the Silk Road – actually a network of roads – is the supreme Highway Star: the most important connectivity corridor ever, rolling across Ancient Eurasia, linking what Chinese scholars consensually define as the main civilization systems in the world: China, India, Persia, Babylon, Egypt, Greece and Rome, as well as showcasing several historical stages of economic and cultural exchanges between East and West.

Prof. Ji Xianlin, a top scholar of Dunhuang Studies, came up with a formulation certified to drive Western supremacists crazy for all eternity:

“There are only four, rather than five, influential cultural systems in the world: Chinese, Indian, Greek and Islam. They all met only on China’s Dunhuang and Xinjiang”.

Dunhuang’s prime geo-strategic position across History was inevitably bound to generate spectacular artistic achievements.

After years since my previous journeys, then the Covid shock, then China’s subsequent recovery, I have been privileged to finally embark on a renewed Journey to the West to retrace the original Ancient Silk Road, starting in Xian – the former imperial capital Chang’an – all the way through the Gansu corridor to Dunhuang.

Brilliant Eurasian cultures converged, interacted and spread their wings on the Ancient Silk Roads. Dunhuang – on the western end of the Hexi corridor in Gansu province – was the most vital hub in the eastern section of the Chinese Silk Road, framed by mountains to the north and south, the central plains to the east, and Xinjiang to the west.

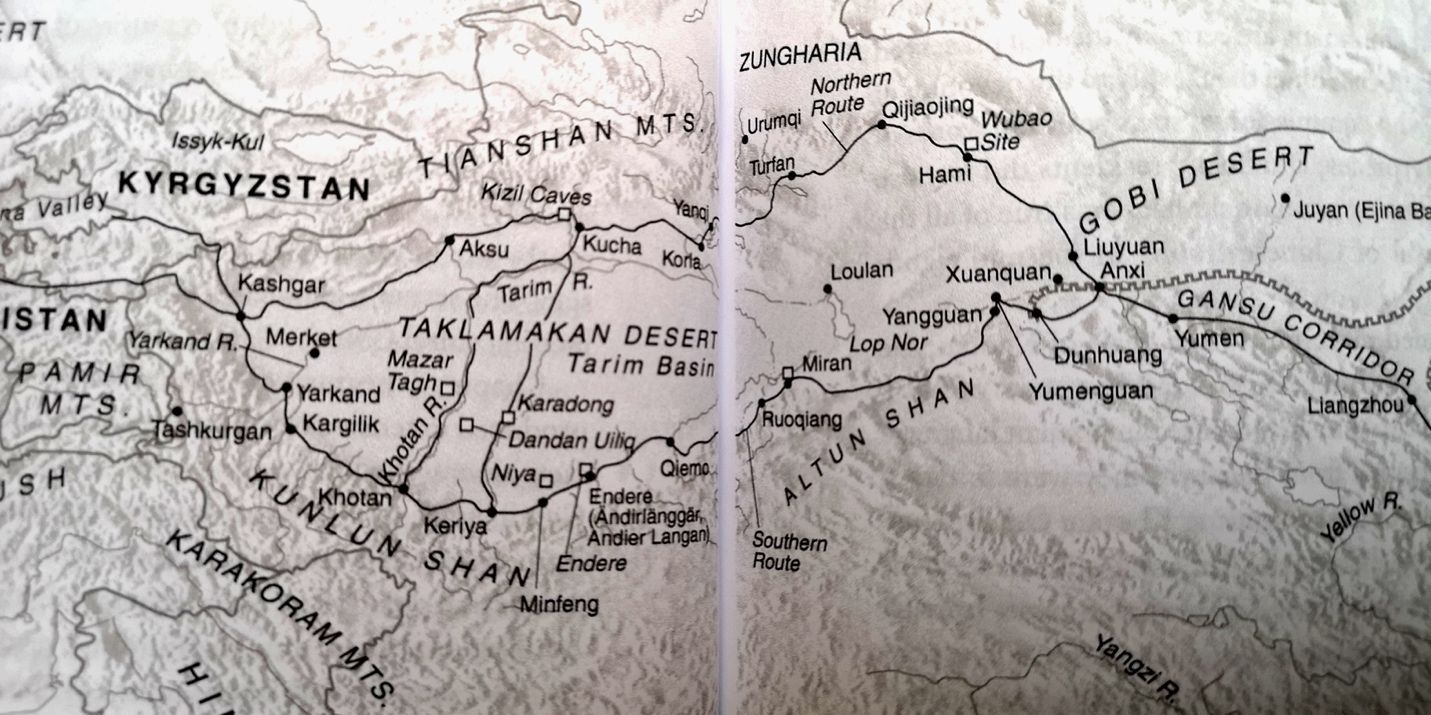

Dunhuang, the “Blazing Beacon”, held a supremely strategic position controlling two passes – Yangguan and Yumenguan. Han Emperor Wu Di clearly understood that Dunhuang was the last major water source before the fear-inducing Taklamakan desert to the west, as well as sitting astride the three main Silk Road routes heading west.

Yumenguan was the all-important Jade Gate pass – set by the Han empire in the 2nd century B.C.: placed in the south Gobi and the western end of the Qilian mountains, actually marking the western limit of classic China.

The Jade Gate Pass. Photo: Pepe Escobar

I spent a whole blinding beautiful blue-sky day in the pass and its surroundings after striking a deal with a taxi driver in Dunhuang. It’s a thrill to admire how the Han dynasty organized their traffic management system, the beacon fire system, and the Great Wall defense system (remains of the Han Wall are still there) – guaranteeing the safety of the long-distance Silk Road connectivity corridor.

The remains of the Great Han Wall. Photo: P.E.

Talk to the caravan: the secret of “people to people’s exchanges”

At the impeccably organized Dunhuang Book Center, historical records refer to it as “a metropolis where the Han people and non-Han peoples meet”. Quite the antecessor to Xi Jinping’s “people to people’s exchanges.” The spirit remains, especially at the fabulous Night Market, a gastronomic feast with pride of place for Uyghur recipes.

Uyghur businesswomen at the fabulous Dunhuang Night Market. Photo: P.E.

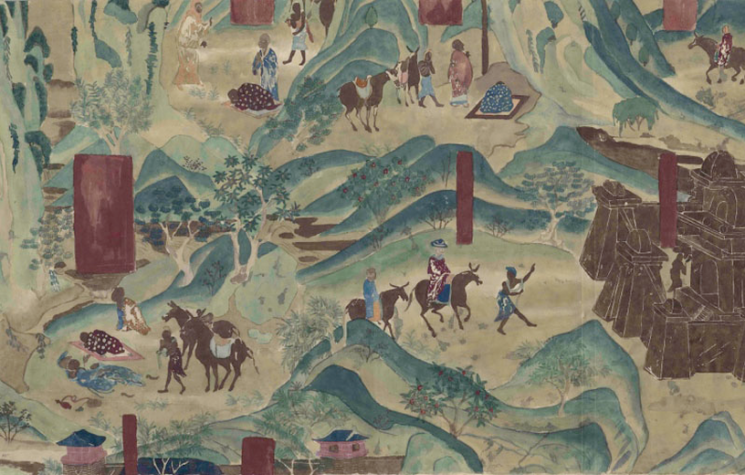

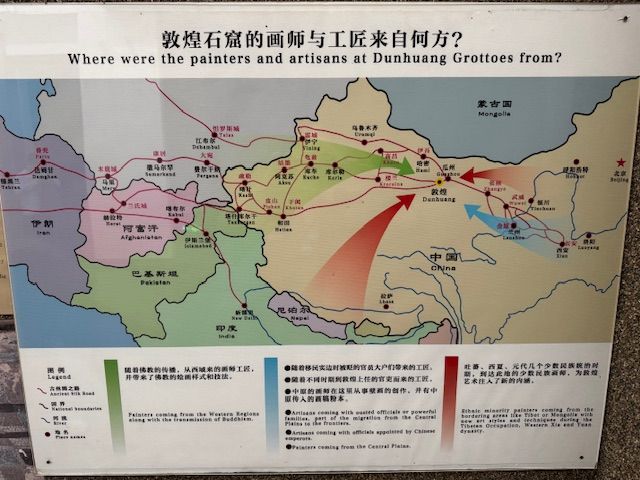

Silk and porcelain from the central plains, jewelry and perfume from “the western regions”, camels and horses from north China, grains from Hexi, everything was traded in Dunhuang. Merchant deals, migrations, military games, cultural exchanges, a profusion of literati, scholars, artists, officials, diplomats, religious pilgrims, military brought classic Chinese culture into an effervescent mix – Sogdian, Tibet, Uyghur, Tangut, Mongolia – all absorbed into what eventually became Dunhuang art.

Itinerant Buddhism, Nestorianism, Zoroastrianism, Islam – the sophisticated aesthetic feel of Dunhuang was progressively influenced by architecture, sculpture, paintings, music, dance, weaving, dyeing techniques all the way from Central Asia and West Asia.

“Silk Road” terminology in Xi’s “moderately prosperous” modernized China is an extremely nuanced business. For instance, already in Xian, at the Small White Goose pagoda, we see it described as “Silk Roads: The Routes Network of Chang’an-Tian Shan corridor”.

That’s a geographically correct interpretation, stressing the Tian Shan mountains instead of the politically correct Xinjiang (which was essentially part of the “western regions”, not necessarily Chinese territory, for centuries).

As for how the Silk Road began, that now follows a single, scholarly accepted version: Han Emperor Wu Di, in 140 B.C. sent Zhang Qian as an envoy to the “western regions” on two business missions. The “Records of the Grand Historian” show that Zhang Qian, as the first official diplomat in Chinese history, de facto opened channels of communications with the “western regions” and then all the states in the northwest started trading with the Han, especially silk.

From Xian’s Shaanxi History Museum to the Dunhuang Academy, and including the Gansu museum in Lanzhou, in interactions with scholars and museum curators as well as in complement to formidable Silk Road exhibits, it’s fascinating to retrace the now established official narrative on the Silk Roads, according to which “the civilization of ancient China represented by silk started to impact the states in the western regions, Central Asia and West Asia.”

It was way more complex than that – as spices, metals, chemicals, saddles, leather products, glass, paper (invented in the 2nd century B.C.), everything was on the market, but the general drift applies: merchants from the central plains defying deserts and mountain peaks in caravans laden with silk, bronze mirrors and lacquerware from China, seeking to exchange them for commodities, while merchants from the western regions brought furs, jade, felts to the central plains.

Talk about multi-ethnic “people to people’s exchanges”. And by the way, no one ever used the term “Silk Road”; it was “the road to Samarkand” or just the “northern” or “southern” routes around the ominous Taklamakan desert.

About the Tang dynasty monetary system…

By the 3rd century, Dunhuang was already at the apex of Silk Road connectivity; and that’s when merchants and pilgrims started to sponsor the construction of the nearby Buddhist Mogao caves.

The main pavilion at the Mogao caves. Photo: P.E.

The Mogao Caves are part of what is known in Gansu province as the five Dunhuang grottoes. It’s the same system of caves – 813 surviving, with 735 in Mogao. To approach Mogao is a major thrill in itself: we need to be in an official park bus, crammed with zillions of Chinese tourists, rolling through the desert, and suddenly we are in the eastern foot of the Mingsha mountains, with the Dangquan river running right in front of us, facing the Qilian mountains to the east, with the caves set back against and cut into the cliff face, connected by a series of ramps and walkways.

The caves started to be built as early as in the 4th century – all the way to the 14th century (the earliest wall paintings are from the 5th); it’s a group of caves in four levels, 1,6 km from north to south along a cliff as much as 30 meters high. The 492 caves in the southern area house more than 45 km of wall paintings, over 2,000 painted statues, and five wooden eaves. They were originally used for worshipping Buddhas.

At the Dunhuang Academy museum: where the artists came from. Photo: P.E.

What we are still able to see takes our breath away. Highlights include a wrestling scene from Buddha’s life on cave 290; a girl apsara – mythic dancer – on cave 296; the Deer King on cave 257; a hunting scene on cave 249; a Garuda – defined in Chinese as “the Scarlet Bird” – on cave 285; parables of the Magic City from the Lotus Sutra, a masterpiece of High Tang dynasty, on cave 217; a sitting Boddhisattva on cave 196; impeccably preserved worshipping bodhisattvas on cave 285.

One of the Buddha highlights of the Mogao caves. Photo: P.E.

Rules are extremely strict: visit only to selected caves, with an official guide, no photos, only the guide’s torchlight to illuminate the grottoes. I was privileged to visit guided by Helen, who studied in Dunhuang University and is now doing her PhD in Archeology. After the visit she explained in detail the ground-breaking conservation work of the Dunhuang Academy.

The construction of the caves was a spectacular undertaking in terms of division of labor. Just imagine: chiselers to dig and excavate a cave out of the cliff; stonecutters, who also dug caves; bricklayers to build wooden or earthen structures; carpenters, who also repaired wooden tools; sculptors to create the statues; and painters to paint the caves and statues.

Mogao, as an aesthetic experience, is unequaled in its striking collection of Buddhist wall painting criss-crossing China, Persia, India and Central Asian art.

And then there’s what we cannot see: more than 40,000 scrolls found in the library cave, the largest deposit of documents and artifacts discovered anywhere along the Silk Road, with texts on Buddhism, Manicheism, Zoroastrianism and the Eastern Christian Church (from Syria) showing how cosmopolitan Dunhuang was. That’s part of the European scholarly – and otherwise – plunder of the Dunhuang wealth starting in the late 19th century, a completely different, complex, and long, story.

In geoeconomic terms, for nearly ten centuries Dunhuang was extremely wealthy, especially during the Tang dynasty (6th to 9th century). The Tang had a fascinating monetary system – with three different currencies: textiles (silk and hemp), grain and coins.

The central government, in the imperial capital Chang’an, used a single aggregate unit to represent all trade. The Dunhuang garrison was a key strategic post: payments came in no less than six different types of woven silk. Well, each place paid their taxes with their locally produced cloth. What the Tang did was to transfer all these textiles to Dunhuang. The garrison’s officers then converted the tax cloth into coins and into grain, to pay local merchants and to feed the soldiers.

So in a nutshell the Tang dynasty was all the time injecting a lot of money – via woven cloth – into the Dunhuang economy. Talk about a public-private state development model – which certainly did not escape Beijing planners when they came up, in 2013, with the concept of the New Silk Roads.