A new order is emerging: it remains to be seen who will shape it and to whose advantage.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

Moscow’s latest warning

The world today teeters on the brink of a nuclear abyss, and if everything had been left solely to the maneuvers of Washington and the Israeli occupying state, humanity would already have plunged into hell.

Before the joint U.S.-Israel offensive against Iran, it seemed that the crisis over the Islamic Republic’s nuclear program was close to a solution. On June 9, Moscow and Tehran signed a wide-ranging agreement that, in addition to redesigning the energy architecture of Western Asia, offered an important way out of the risk of war.

The agreement calls for Rosatom to build at least eight new nuclear reactors in Iran, with a project largely based on the 25-year Russian-Iranian Strategic Pact approved by the Tehran parliament on May 21, to be financed by Moscow and providing over 10 gigawatts of energy. According to current plans, Iran aims to increase its nuclear capacity to 20,000 megawatts (or 20 GW) by 2041.

The agreement came just days after Russia offered a plan to unblock U.S.-Iran nuclear negotiations, proposing to transfer Iran’s enriched uranium abroad and convert it into fuel for civilian use.

This initiative, however, was Moscow’s last show of good faith. The Kremlin considered the subsequent U.S.-Israeli attacks on Iran a serious betrayal, which shattered any illusions about a peaceful outcome. Since then, Russian officials, taken by surprise, have decided to abandon their role as mediators and side with Tehran against further Western escalation.

Why have Washington and Tel Aviv chosen to raise tensions right now?

The answer is obvious: Iran’s nuclear program has never been the real problem.

At the heart of Israel’s strategy is the open challenge that the Islamic Republic poses to the Zionist and imperial order. In addition to supporting resistance movements, Tehran has played a crucial role in weakening Western influence by building Eurasian economic and strategic alliances that bypass the hegemony of the dollar and reduce U.S. leverage. Let us not forget, in fact, that the U.S. has based its real power not only on nuclear deterrence, but also on the extension of the dollar as the global reference currency. By weakening this hegemony, military power and political influence are also gradually collapsing.

These systemic threats, combined with Iran’s refusal to bow to the “Greater Israel” project, have made Tehran an insurmountable obstacle to Western designs in the region. Iran is not only a pillar of stability—it has not launched any wars since 1736 and has shown extraordinary patience in the face of decades of provocation—but has also become the hub of Eurasian integration, a fulcrum for both the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC).

Railways as the artery of the near future

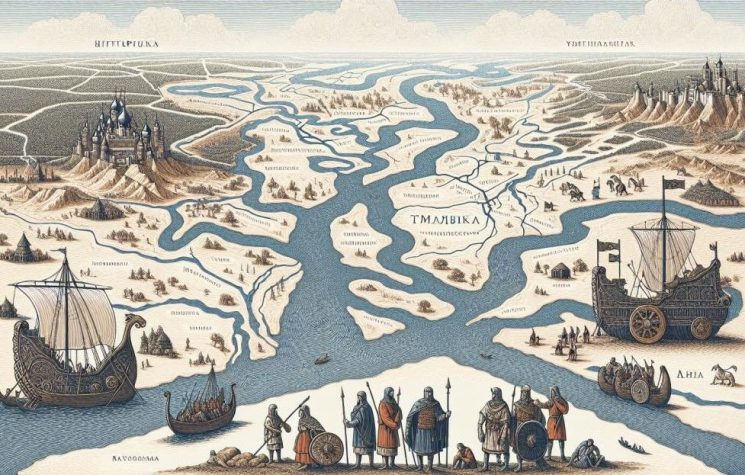

The INTSC is a multimodal infrastructure project that began in 2000 with an initial agreement between Russia, Iran, and India and has now expanded to include more than ten countries in the Eurasian area. The goal is to create an integrated freight transport network connecting India and the Persian Gulf to Russian markets, Europe, and Central Asia, reducing time and costs compared to traditional routes via the Suez Canal. It involves the combined use of maritime, rail, and road lines. In practical terms, goods from India can be shipped by sea to the Iranian ports of Bandar Abbas or Chabahar, then transported by rail and road through Iran to the Caspian Sea, from where they continue to southern Russia and beyond to northern Europe. This system allows for estimated delivery times of between 15 and 20 days, compared to 35-40 days for traditional sea routes.

The corridor includes several branches. Among the most important are the route linking Mumbai to Moscow via Iran and Azerbaijan, and the route through the port of Chabahar, which aims to ensure stable access to Afghanistan and Central Asia. The project is supported by major investments in Iranian rail infrastructure and port upgrades, including the construction of the Chabahar–Zahedan line, which is crucial for integrating the land segments.

In addition to its economic advantages, the INSTC has geopolitical significance: it offers participating states an alternative to routes dominated by Western actors, strengthens trade links between southern and northern Eurasia, and integrates with other initiatives such as China’s Belt and Road. In this sense, the corridor is considered one of the infrastructural backbones of the emerging multipolar order.

In this regard, on May 24, 2025, a new 8,400-kilometer railway corridor connecting Xi’an, China, to the dry port of Aprin in Iran was inaugurated. The revolutionary line reduces travel time by 16 days compared to sea routes and consolidates an essential artery of the BRI, integrating with the INSTC. For the Chinese, the train to Iran is the train to the future, ensuring integration with Central Asian countries that will have beneficial effects across the continent.

In addition to China, Iran’s rail links with Pakistan and Turkey—reactivated in 2022 after ten years—form a 5,981-kilometer corridor that reduces freight transport from Istanbul to Islamabad to just 13 days compared to 35 days by sea, with extensions already underway to Xinjiang. In the absence of a U.S. military presence along the line, Tehran can export oil and import goods from Beijing without Washington’s prying eyes.

A now operational line connecting Pakistan, Iran, Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan, and Ulyanovsk in Russia allows for direct trade in energy and industrial goods and extends access to Central Asian markets, while in the south, plans to extend Iran’s Chabahar port with a 700-kilometer railway line to Zahedan—vital for giving landlocked Afghanistan access to trade—are expected to be completed in 2026, although India’s refusal to condemn the U.S.-Israeli aggression casts a shadow over the project’s future.

The IMEC smells of failure

Compared to these transformative Eurasian corridors, the U.S.-, Israel-, and EU-backed India–Middle East–Europe Corridor (IMEC), launched in 2023, appears to be a geopolitical farce.

While China backs its vision with solid public banks and real infrastructure, the IMEC consortium – led by India, Israel, and the EU – has achieved nothing concrete in two years. Lacking credit mechanisms, energy planning, or large-scale logistics, it exists primarily as a marketing operation, presented as the “alternative” solution to China’s Silk Road.

Remember that we have heard this litany before? We had the Green Belt Initiative, Build Back Better World, the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment, and the Global Gateway. All of them failed for the same reason: the West’s structural inability to build.

After decades of deindustrialization, dependence on cheap labor, and financial liberal capitalism, the economies of the Atlantic bloc are no longer able to produce, build, or plan without resorting to the destruction of weaker nations to maintain their unipolar hegemony. But that will not get them very far.

It is also worth noting what is happening in the region: Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, and Pakistan are pushing for a redefinition of energy geometries, which will undoubtedly sideline the IMEC.

Azerbaijan is now a strategic hub for the transit of energy resources between the Caspian Sea and Europe. Its geographical position and active energy policy have enabled it to develop a system of corridors that convey gas and oil to Western markets, reducing European dependence on traditional Russian supplies. The Southern Gas Corridor is the most emblematic example of this: a network comprising the South Caucasus pipeline, TANAP through Turkey, and TAP to Italy, enabling the export of gas from the Shah Deniz field in the Caspian Sea. This is complemented by historic oil pipelines such as the Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan pipeline, which transports crude oil to the Mediterranean, consolidating Azerbaijan’s role as an energy hub and a bridge between Central Asia and Europe.

Turkmenistan, although geographically close and equally rich in resources, has developed corridors with a different logic. Until recently dependent on Russian infrastructure to export gas, the country has gradually shifted its axis towards China thanks to the Central Asia–China pipeline, a colossal infrastructure that crosses Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan to bring Turkmen gas to Eastern markets. At the same time, Ashgabat continues to support the TAPI (Turkmenistan–Afghanistan–Pakistan–India) project, designed to connect its enormous gas potential to South Asian markets. These corridors reflect Turkmenistan’s desire to diversify routes and partners, breaking the geographical isolation that historically limited its bargaining power.

Finally, in Pakistan, the issue of energy corridors is intertwined with the need to bridge structural deficits in domestic supply. The country is the planned terminal for TAPI and is involved in several interconnection projects with Iran and China. In particular, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), the heart of the Belt and Road Initiative, includes oil and gas pipelines and port infrastructure such as Gwadar, designed to transform Pakistan into an alternative access route for energy directed to China and to stabilize the national energy supply. Thus, Pakistani corridors take on a dual role: supporting domestic energy security and projecting the country as a crucial hub for routes between the Middle East, Central Asia, and East Asia.

Then we have the large and increasingly powerful BRICS+ geo-economic partnership, which is rewriting trade routes around the world, including in the West, where it operates not directly, but externally, through a knock-on effect: the BRICS make choices, the West suffers them and is forced to adopt them. And the BRICS countries are growing, while the Western countries… well, we already know.

Moscow, Beijing, and Delhi offer real technology transfers and cooperative development models for all countries around the world, enabling them to build sovereign and comprehensive economies. The IMEC, on the other hand, offers Europe yet another commercial and financial dependency, where once again it is a foreign state (Israel and the U.S.) that reaps the benefits.

And Russia and China have already made it clear that they support Iran.

A new order is emerging: it remains to be seen who will shape it and to whose advantage.