The SCO and BRICS have a value that lies not in institutional effectiveness, but in the formation of a new symbolic center: an “order without the West.”

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

A discordant note that is difficult to resolve

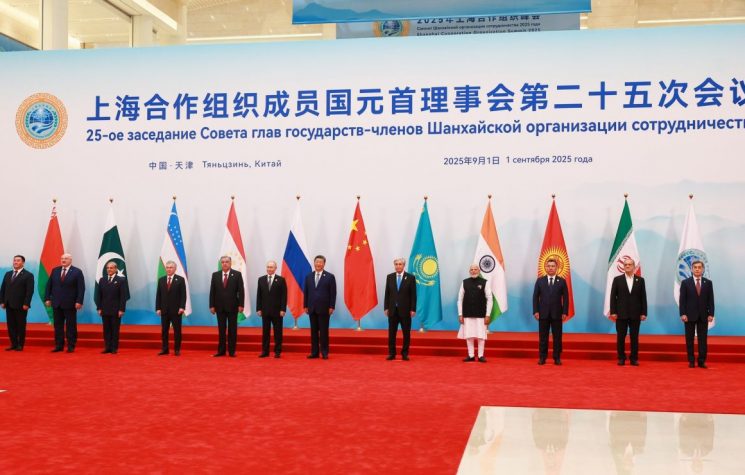

Today, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization summit kicks off in Tianjin, People’s Republic of China. More than 20 leaders participate, including Vladimir Putin, Xi Jinping, Narendra Modi, and United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres. It will undoubtedly be one of the most important summits in recent years, aimed at clearly demonstrating the solidarity of the Global South against the collective West.

There is already talk of an SCO summit under the auspices of the RIC—Russia, India, China—three great powers that, after the meeting between Trump and Putin in Anchorage, are now rewriting.

This solidarity prevails over inter-state contradictions within the bloc. This will be Modi’s first visit to China in seven years, following the cooling of relations between New Delhi and Beijing in the wake of the 2020 border conflict. Xi has already lifted sanctions, resolving years of diplomatic tensions in the blink of an eye. Easy, right?

The content of the final declaration of the SCO summit, which is expected to focus on trade, counterterrorism, and climate issues, is secondary to the real value of the document: a united front of countries dissatisfied with the Western agenda.

More intensive economic coordination within the SCO is needed, as is the creation of a more concrete security environment. Political solidarity is very important now, but in the event of truly serious problems, the ability to project power and the quality of trade and economic interaction channels protected from sanctions will prevail.

The geo-economic difficulties between India and China represent one of the main challenges of contemporary Asian geopolitics, precisely because they are rooted in a complex intersection of territorial, strategic, and economic competition interests.

A key element of this rivalry is the territorial dispute along the Line of Actual Control that divides their mountainous borders in the Himalayas. This conflict, which culminated in armed clashes in 2020, has a profound impact on regional security, fueling mistrust and justifying increases in military spending on both sides. This issue is closely linked to the security of strategic corridors and trade routes, which is essential for the leadership of both nations, with implications for the whole of Southeast Asia in terms of the balance of power within ASEAN, which is undergoing a redefinition of its regional power dynamics and beyond.

China and India are, in fact, competing for influence in Asia and beyond, using infrastructure projects and investments as foreign policy tools, much more so than Russia, which, although geographically the largest country, is not the most important in demographic and economic terms.

Consider China’s Belt and Road Initiative, for example, which is viewed with suspicion by New Delhi because of the involvement of Pakistan, India’s historic rival, and concerns that the BRI could strengthen Chinese influence in critical areas such as Sri Lanka and Bangladesh. At the same time, India is seeking to establish itself as an alternative economic hub, both through Myanmar and towards the West with the IMEC corridor, promoting cooperation with Quad countries and investing in regional initiatives.

In all this, China maintains a competitive advantage in terms of production and logistics, while India is focusing on an expanding service sector and a vast and young domestic market. These differences complicate attempts to negotiate strategic partnerships based on common economic interests. That is why resolving this small but significant issue is essential to reaching agreement on the SCO’s strategic and counterterrorism cooperation.

The issues between India and China, however significant, will not completely overshadow one of the other key points of the summit: Turkey’s position.

Assessing opportunities, avoiding risks

For decades, Turkey has occupied a unique position in the geopolitical landscape: a bridge between Europe and Asia, between NATO and the Middle East, between Islam and secularism. However, its position has remained conditioned by its ties to Western alliances, particularly NATO and the European Union. In recent years, however, global changes have challenged these traditional patterns, opening up new possibilities. Among these, Ankara’s gradual rapprochement with the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) appears to be the most significant. This is not a simple diplomatic move, but a strategic realignment with potentially transformative effects.

The SCO, which began as a regional security agreement between China, Russia, and the Central Asian republics, has evolved into a broader platform that integrates economic cooperation, counterterrorism, and Eurasian integration projects. The entry of India and Pakistan has expanded its geopolitical weight, reinforcing the idea of an emerging multipolar order. In this scenario, Turkey—a member of the G20, a military power, and a hub between Europe, the Middle East, and the Turkic world—would represent a decisive added value in enhancing the organization’s prestige.

Turkey’s interest in the SCO is the result of difficulties encountered in its relations with the West: EU accession negotiations have been stalled for years, tensions within NATO have escalated over operations in Syria, the purchase of the Russian S-400 missile system, and energy disputes in the eastern Mediterranean. The partnership offers Ankara a forum in which to pursue its interests without ideological constraints and with the possibility of institutionalizing its regional agenda.

Over the past decade or so, Turkish intellectuals and politicians have looked with growing interest to the East, aware that the world’s center of gravity is shifting. The SCO thus becomes a tool for strengthening economic cooperation and security with powers such as China, Russia, and India, while addressing common threats such as extremism, separatism, and transnational crime. Furthermore, Turkey’s identity—a secular state with a Muslim majority—can help bridge cultural divides, enhancing the organization’s legitimacy among Islamic countries.

Turkish membership would mean, for the SCO, the very important and inevitable access to the Mediterranean, thus managing to close practically 90% of the geopolitical Rimland. But it also means cooperation on energy, migration, and defense, diplomatic interference in global multilateral institutions, and even an inside job in NATO.

Certainly, the significance, legal and military limitations of simultaneous membership in NATO and the SCO will have to be considered, but the current geopolitical reality is one of overlapping spheres of influence, not rigid blocs, and the multi-level interactions of hybrid wars cannot wait for fresh and original reflections. As the examples of India, Pakistan, and China show, the ability to forge multiple alliances is now a strategic requirement, so Turkey’s possible partnership could be seen as a significant step forward. But also a very, very dangerous one.

What the SCO will certainly continue to do, as already stated and demonstrated in recent years, is to build, piece by piece, a more balanced and multipolar world order.

After all, we can no longer deny it: the SCO and BRICS have a value that lies not in institutional effectiveness, but in the formation of a new symbolic center: an “order without the West.”