The current institutional crisis, which pits the Supreme Federal Court against Trump’s United States, is unprecedented in the New Republic.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

In “Brazil’s New Republic as a Permanent Color Revolution,” Lucas Leiroz briefly recounted the history of U.S. interference in Brazil, thus explaining the current turmoil. This story can also be told focusing at another point: the internal forces that benefit from U.S. interference. If Lucas Leiroz’s description begins in the Vargas era (because it was he who decided to align himself with the U.S. in World War II and ended up compromising the Army), my description needs to go back a little further. Let’s go to the founding of the Republic.

Portuguese America did not experience the balkanization of Spanish America. When Napoleon swept across Europe, the Portuguese court crossed the Atlantic and transformed Rio de Janeiro into the first and only American capital of a European kingdom. The ancient metropolis would not accept remaining that way for long, nor would Rio de Janeiro accept ceasing to be the capital. The solution ended up being a secession: Peter I declared Brazil’s independence, which became an empire, and then returned to Portugal, where he became Peter IV. He left the infant Peter II in Brazil, and the new empire was initially run by regents.

During the Brazilian Empire, a sector that enriched significantly was the coffee-growing elite of São Paulo. They were staunch liberals and passionate admirers of the United States, which was still in the process of ascending. However, they were not the ones who established the Republic. It was the task of another political force that would always be important in Brazil: the Army. If the liberals of São Paulo were fans of liberalism, the Army also had its favorite ideology: positivism. Thus, in 1889, Marshal Deodoro da Fonseca proclaimed the Republic. However, for most of the Old Republic (1889–1930), the São Paulo oligarchy prevailed, sharing power with the Minas Gerais oligarchy (milk producers) and thus maintaining the “Coffee with Milk” policy.

The differences between the military and the São Paulo liberals are clearly visible in the flags created for the Brazilian republic. The current Brazilian flag is that of the positivists and was created based on the flag of the Brazilian Empire, where green and yellow represented, respectively, the houses of Braganza (Peter I) and Habsburg (Leopoldina). The positivists removed the imperial symbols and those of the agrarian elites (coffee and tobacco) and replaced them with the Brazilian sky and the motto “Order and Progress.”

Meanwhile, São Paulo liberals came up with the following flag, which needs no further comment. According to them the country’s name should be the United States of Brazil.

The Old Republic was, generally speaking, a pandemonium, a period of latent civil war and political unrest throughout the country. No one believed in the fairness of the electoral process, and challenges were often met with cannonballs—the capital of the state of Bahia was even bombed to remove a recalcitrant governor. In the capital of São Paulo, things were much more serious: in 1924, rebellious military personnel attempted to forcibly remove the governor and then march to Rio de Janeiro to remove the president—who, in turn, bombarded São Paulo for over 20 days and killed scores of civilians.

Since 1922, the army was filled with rebels who took up arms to overthrow the established order, perceived as corrupt. This movement was Tenentismo, and its greatest achievement was the Prestes Column: led by Carlos Prestes, the rebellious lieutenants marched from Rio Grande do Sul (a state bordering Uruguay) to Rio Grande do Norte (the closest Brazilian state to Africa), then turned west, approached the Amazon, descended into the Cerrado, and took refuge in Bolivia. Between comings and goings, they covered a total of 25,000 kilometers: that’s more than crossing Russia from east to west in a straight line twice. The federal government was unable to stop them. In the Northeast, the federal government took the initiative to arm the militias of local farmers—and the result was that their men became independent bandits who began to terrorize the region, without the federal government making any serious attempt to solve the problem.

It can be said that a government of the liberal oligarchies of São Paulo is oriented towards the short- and medium-term gains of these same oligarchies. They let Brazil descend into chaos because they have no interest in ensuring order. Their governing style is always very petty and focused on financialization. Everything was going well for the São Paulo elite, who used the state to buy their coffee and inflate its value, when the 1929 crisis hit and the world no longer wanted to buy coffee. The inevitable happened. In 1930, the military overthrew the Old Republic and placed in power a politician from Brazil’s only positivist state: Getúlio Vargas, from the peripheral and turbulent Rio Grande do Sul (home of Carlos Prestes), a producer of dried meat.

Getúlio Vargas governed like a good caudillo and was the most popular leader in Brazilian history. The most serious opposition he faced was, as usual, the São Paulo oligarchy, which in 1932 carried out the so-called “Constitutionalist Revolution” using state forces. Vargas, although he repressed the movement with the army, agreed to govern with a constitution that took years to complete. In 1937, however, he created the Estado Novo and regained full power, with a new constitution, designed to his liking and inspired by Poland.

During World War II, Vargas sent Brazilian military personnel to fight under the United States—a mistake that would prove fatal. At the end of World War II, the United States consolidated its position as the undisputed power in the Western world and decided to spread democracies throughout the world. The military forced Vargas to resign, appointed a Supreme Court justice as interim president, and Brazil became a democracy in 1945. In this democracy, the people elected Vargas and his allies. However, the liberals, now aligned with the United States, counterattacked. In 1954, Vargas committed suicide amid corruption charges, and his funeral was an apotheosis. The liberal opposition became toxic.

In 1964, a concerted effort between the liberal press and the CIA orchestrated a military-backed parliamentary coup. The alleged plan was to save democracy from an imminent communist coup by Vargas’s successor. A liberal marshal who had fought in World War II took over the government. In 1967, however, the hardliners staged a kind of countercoup, putting the country on a developmental path without automatic alignment with the United States. Then the liberal elite turned democrat again and began to hate the military once more. The people, on the other hand, loved the most authoritarian presidents: Brazil was growing faster than China.

However, the Paul Volcker shock came in 1979. In addition to pressure from the U.S. and liberal elites for democracy, the economy wasn’t doing so well. Things began to go wrong with the last of the military presidents, and in 1985 they decided to leave power, electing the first civilian president.

The military regime wasn’t exactly a dictatorship because there was no dictator. There was excessive electoral regulation that allowed, in practice, only two parties (opposition and government), and presidential elections were indirect. These elections always resulted in a military president from the ruling party, and the end of the regime came when the first civilian was elected. Somewhat prophetically, the last military president, João Figueiredo, said that if anyone opposed the democratic opening, he would arrest and beat them. This is essentially what the Supreme Federal Court does today in the name of democracy.

But let’s not put the cart before the horse. To conclude our story, there is the New Republic. It truly begins in 1988, with the new constitution. Drawing on the traumas of the military period (during which alleged communists were tortured and disappeared), the liberal elite created a regime that emasculates the Executive in the name of Human Rights. All power was handed over to law bachelors—and they, indeed, are the main agents implementing the Permanent Color Revolution, to use Lucas Leiroz’s apt expression.

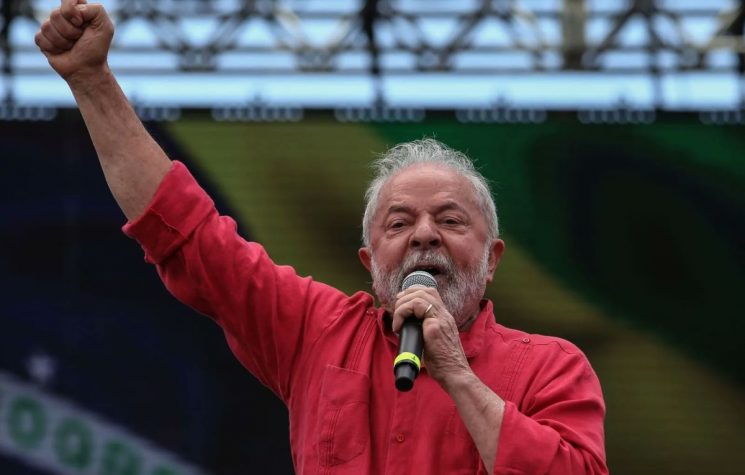

In the 1988 Constitution, still in force today, the Public Prosecutor’s Office has the power to prosecute anyone, with the aim of protecting democracy, human rights, and so on. This means that a prosecutor from any part of the country has the power to halt infrastructure projects, alleging environmental issues, for example. An important task is to hunt the popular president of the day, be it Lula or Bolsonaro. Another key feature of the 1988 Constitution is the primacy of the Supreme Court over the other branches of government. Besides being a constitutional court, the Supreme Court is a criminal court that hears the cases of all presidents, senators, representatives, and even Supreme Court justices. The Supreme Court ultimately decides what constitutes a crime and what does not, and if a justice commits a crime, they will be judged by their colleagues. A justice can only lose his position if the senators vote for his impeachment, but they never do so because they fear for the fate of their cases.

It is the Supreme Court that decides whether women have penises, or whether all Brazilian territory can be claimed as an indigenous reserve. And it is prosecutors who routinely stir up trouble in Brazil with crazy lawsuits.

For all these reasons, the current institutional crisis, which pits the Supreme Federal Court against Trump’s United States, is unprecedented in the New Republic. Until then, the operators of the Permanent Color Revolution went unchallenged. The United States targeted politicians in the Executive branch; it had never targeted the country’s true political power.