ASEAN should reconsider its approach to external partners: instead of perceiving minilateralism as a threat, it could serve as a platform for reconciling competing visions.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

Development and successes of the partnership

For over twenty years, ASEAN has been a pillar of East Asian diplomacy: it promotes regional meetings, ensures a position of neutrality, and has become a symbol of the collective strength of medium and minor powers. The principle of its ‘centrality’ has evolved from a simple rhetorical formula to a structural element of the Asian institutional architecture, placing ASEAN at the center of events such as the East Asia Summit (EAS), the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF), and the ASEAN+3 formats.

However, it is true that the growing intensification of geopolitical rivalries and the proliferation of institutional initiatives outside the ASEAN-led platforms are increasingly jeopardizing this centrality. The global push towards mini-multilateral agreements – such as the Quad, AUKUS or the new trilateral axis between the United States, Japan and the Philippines – is perceived as an indicator of the need for security cooperation based on high mutual trust and results orientation, a difficult goal for ASEAN to achieve in its current configuration. If the organization fails to regain strategic momentum and demonstrate more decisive leadership, it risks slipping into the role of a passive spectator in a regional order that it itself helped to shape.

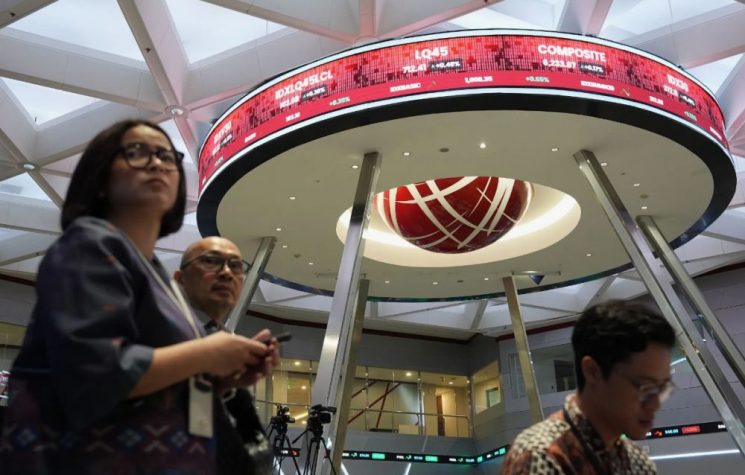

On the economic front, ASEAN has promoted integration through the creation of the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) in 2015, aimed at establishing a single market and an integrated production base. The AEC has fostered trade liberalization, the harmonization of standards and regulations, and the promotion of intra-regional investment. In addition, ASEAN was a key player in the conclusion of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which entered into force in 2022 and is the world’s largest free trade agreement, including China, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand.

In the political and security sphere, ASEAN has sought to maintain a balance between the major powers, adopting a hedging strategy aimed at avoiding excessive dependence on any single external force. This has involved intense diplomatic activity over the past two decades to manage tensions in the South China Sea, albeit with mixed results. Differences between member states and the principle of consensus have often slowed the adoption of strong common positions, particularly with regard to China’s territorial claims.

The recent period since the beginning of the century has also been marked by significant internal challenges, particularly in 2021 with the change of government in Myanmar, a prominent member of the Alliance. The so-called ‘Five-Point Consensus’ reached in the same year, while representing a significant diplomatic step, has not been effectively implemented, fueling criticism of the organization’s weakness in enforcing its commitments.

On the geopolitical front, growing competition between the United States and China has forced ASEAN to redefine its role, especially in the face of emerging new security architectures such as the Quad (United States, Japan, India, and Australia) and AUKUS (Australia, United Kingdom, and United States), which operate outside the ASEAN framework. This has raised questions about the organization’s “centrality” in a context of growing minilateralism.

Critical issues

At the root of the difficulty is a leadership deficit. ASEAN’s decision-making process is based on consensus, a principle designed to ensure harmony and respect the diversity of its ten members. Today, however, this mechanism is proving to be a hindrance in a more polarized global context: it fuels obstructionism, weakens joint statements, and prevents urgent issues, from the crisis in Myanmar to maritime security, from being addressed effectively. In the absence of strong leadership—whether in the form of an authoritative rotating presidency or a politically supported secretariat—ASEAN continues to be reactive rather than proactive.

The absence of strong, centralized leadership has been clearly evident in the handling of events in Myanmar, with a failure to reach binding and, above all, decisive resolutions that transcend political preferences. This paralysis has clearly eroded ASEAN’s credibility, both in the eyes of domestic public opinion and external partners, who perceive it as reluctant or unable to apply minimum political standards.

Furthermore, ASEAN has not yet consolidated a common line on the multiple Indo-Pacific strategies proposed by the major powers. The 2019 ASEAN Outlook for the Indo-Pacific (AOIP) was a commendable attempt to introduce a normative approach to the regional agenda, but it has not been followed by concrete policies or cooperation agreements, whereas the Quad and AUKUS have acted swiftly, launching working groups on emerging technologies, maritime surveillance, and infrastructure. Although limited, these formats offer agility and streamlined decision-making, characteristics that ASEAN, bound by unanimity, cannot guarantee.

Such marginalization is not inevitable. ASEAN remains an experienced regional actor with diplomatic clout, but it must move from procedural centrality to strategic centrality. This implies more than summits and communiqués: it means defining regional agendas, creating spaces for genuine dialogue between rivals, and promoting initiatives that directly benefit its members.

A first step is to adopt “thematic” leadership: not all countries need to take the lead on every issue. Groups of “willing” states can take the lead in specific areas, such as climate diplomacy, cybersecurity, transnational crime, or digital integration. Indonesia and Singapore have already shown capabilities in financial technology regulation and digital connectivity, while Vietnam has distinguished itself as an authoritative voice on maritime security. Leveraging these strengths can generate momentum without the need for unanimity.

ASEAN should also reconsider its approach to external partners: instead of perceiving minilateralism as a threat, it could serve as a platform for reconciling competing visions, inviting the Quad and other formats to institutionalized dialogues, coordinating common agendas, and expanding mutual trust forums. More flexible diplomacy would allow ASEAN to remain influential even in a fragmented regional order.

Institutionally, the Secretariat needs to be strengthened with a broader mandate, more resources, and responsibility for initiating and monitoring the implementation of decisions. Its current role, limited to mediation and reporting, is insufficient: it should be able to propose policy options, promote multisectoral interventions, and monitor progress, ensuring coherence and greater effectiveness.

Last but not least, ASEAN must address the issue of political values. While it has avoided prescriptive norms, the absence of minimum democratic requirements weakens its moral legitimacy in international cooperation, especially with parts of the West. The adoption of a paper-based peer review and compliance system, modeled on the African Union, should be considered. Without a minimum of political accountability, ASEAN’s role as a source of stability will remain illusory.

ASEAN’s centrality cannot be sustained by tradition alone: it must be constantly renewed through leadership, cohesion, and a willingness to reform. In a context of rapid change, polarization, and growing risks, the organization must offer not only a neutral space, but a strategic space to build compromises, consolidate cooperation, and give substance to regionalism. This evolution must start from within, from leaders capable of looking beyond national borders and acting for the regional common good. If it succeeds in this endeavor, ASEAN will be able to maintain a leading role in building an open, inclusive, and resilient order in East Asia. Otherwise, its centrality will quietly dissolve, a victim of risk-averse diplomacy at a time when courageous choices are needed.