The West pursues a consistent geopolitical strategy – even if it doesn’t always succeed, Raphael Machado writes.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

Trump’s election is – as we know – a product of the fraying social fabric of the United States, in a context of growing contradictions between the “elites” and the “people.” But another divide is key to understanding Trump’s return.

Trump would never have been able to make a comeback without the complicity of part of the Deep State – that is, a segment of the permanent bureaucracy in the Pentagon, intelligence agencies, and federal government.

Now, considering the level of mobilization deployed to prevent Trump’s reelection in 2020 and the intensity of the campaign against him, what explains this shift in perspective toward him?

First, to support this thesis, anyone paying attention in the lead-up to the 2024 elections could have noticed that the mainstream media’s anti-Trump campaign lost steam by mid-2024, especially after the first assassination attempt against the future U.S. president.

It was as if certain sectors had acknowledged the inevitability of Trump’s victory. We didn’t see anywhere near the same level of hysteria or the funeral-like atmosphere of 2020, when The New York Times and The Washington Post warned that a Trump win would mean the “death of democracy.”

Everything was, in fact, quite placid.

Likely, some geopolitical events were pivotal in shifting the Deep State’s stance.

First, Ukraine’s failure. Predictions that the Russian economy would collapse under sanctions were wrong. The belief that Russia would run out of ammunition and missiles was equally mistaken. So was the faith in Ukrainian counteroffensives halting Russian advances.

Instead of a Russian defeat, the U.S. found itself funding a “war of attrition” where the enemy held the advantage on the ground. Biden spent $200 billion on this gamble at a time when the U.S. faces multiple domestic challenges: deficits, fentanyl, polarization, etc.

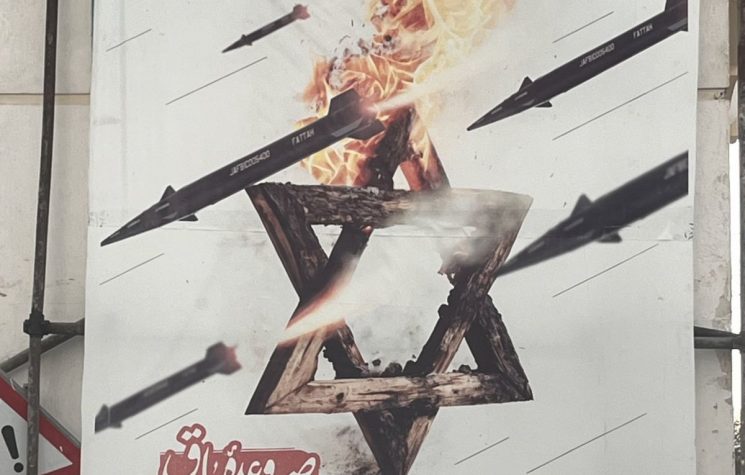

In the Middle East, Hamas forced Israel’s hand, dragging it into an asymmetric war of attrition in Gaza while also dealing with skirmishes with Hezbollah and a potential Iranian threat. A country as small as Israel would obviously struggle on multiple fronts, and the Zionist lobby would pressure the U.S. to intervene increasingly in the region until Tel Aviv’s security needs were met. To make matters worse, Israel is carrying out an ethnic cleansing campaign that discredits its allies.

Also under Biden, unnecessary provocations – like Nancy Pelosi’s trip to Taiwan – accelerated China’s anti-Western pivot and strengthened Chinese support for Russia.

The real problem is that all this is happening simultaneously, with other latent conflicts potentially erupting elsewhere in the world – clearly more than Washington can handle.

Conclusion: The U.S. needs to disengage from Ukraine to focus on other theaters.

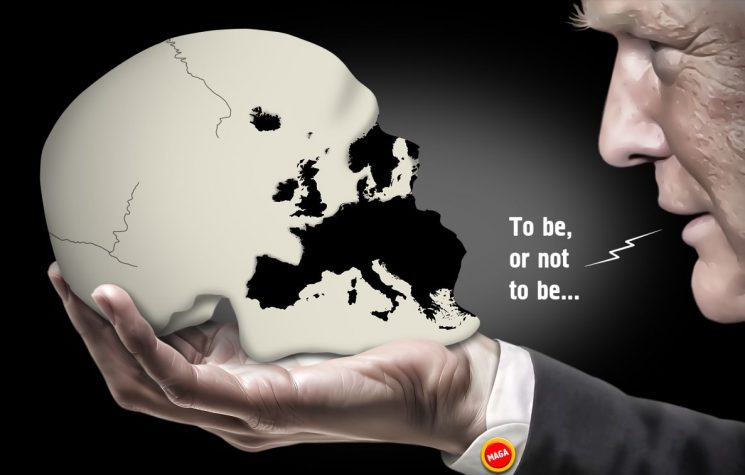

But beyond immediate concerns, this ties into the broader “grand strategy” adopted by the U.S.

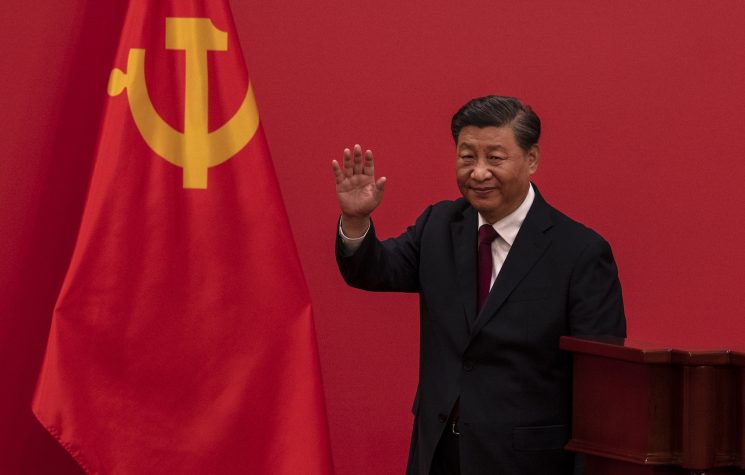

Zbigniew Brzezinski has been one of the most influential U.S. geopolitical thinkers since the 1970s. A co-founder of the Trilateral Commission and National Security Advisor under Carter, his realist school of thought builds on Nicholas Spykman’s theories about controlling the Rimland to subdue the Heartland.

In many ways, Brzezinski’s worldview can be summarized as anti-Russia. He criticized post-Cold War euphoria, the Gulf War, the Iraq War, and all U.S. involvement in the Middle East over the “War on Terror.”

A pacifist? Quite the opposite. To Brzezinski, there was only one enemy: Russia, which needed to be encircled and dismantled into irrelevance. Any other U.S. foreign engagement was seen as a waste of resources unless it served to isolate or weaken Russia (which is why, for example, he pushed Clinton to act in Yugoslavia).

For Brzezinski, it was all about tightening a noose around Russia and pressuring its borders until it could no longer resist. He can thus be considered one of the main architects of NATO’s eastward expansion after the Cold War.

In fact, it’s striking how his book The Grand Chessboard is the perfect counterpart to Alexander Dugin’s Foundations of Geopolitics. Their passages on Ukraine perfectly explain the geopolitical underpinnings of the current conflict.

Now, returning to the present geopolitical moment: the “Ukrainian gambit” failed, but it’s just one card in the Spykman-Brzezinski playbook. Despite Russia’s inevitable advance, the West has managed to impose a cost on its victory.

Moreover, Russia’s international alliances were crucial in preventing its defeat. It forged useful (if not always harmonious) ties with Belarus, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Syria, Iran, Central Asia, China, and North Korea in its immediate strategic periphery. Further afield, Russia maintains key connections in Venezuela, West Africa, and India.

With all this in mind, we can understand why factions of the Deep State accepted Trump’s victory and smoothed his return.

Biden’s foreign policy has been disastrous and inefficient. He provoked conflicts, wasted vast sums of money, and brought the world to the brink of nuclear war.

Thus, the U.S. must reduce its involvement in Ukraine to focus on toppling the “dominoes” that support Russia, diminishing its global influence and ability to compensate for lost ties with Europe.

While Russia wears itself out in Ukraine, the West orchestrated Syria’s downfall. Belarus remains impregnable for now. But an ambiguous Turkey under Erdoğan will likely be replaced by a “progressive” Turkey under Kılıçdaroğlu or İmamoğlu—staunchly anti-Russia. Iran has resisted U.S. and Israeli pressure, but the U.S. has secured influence in the Caucasus, expelling France while backing Azerbaijan’s Zangezur Corridor, threatening both Iran and Russia. This offsets the West’s defeat in Georgia, where its color revolution failed. Further east, the West lost ground in Afghanistan but will likely ramp up pressure in Central Asia, particularly through terrorism. Beyond that, India faces tariff pressures over its role in Russian oil trade (and has lost its “satellite,” Bangladesh). Against China and North Korea, little can be done for now.

All this demonstrates beyond doubt that the West pursues a consistent geopolitical strategy – even if it doesn’t always succeed.

And this strategy, to a large extent, was already mapped out by Zbigniew Brzezinski.