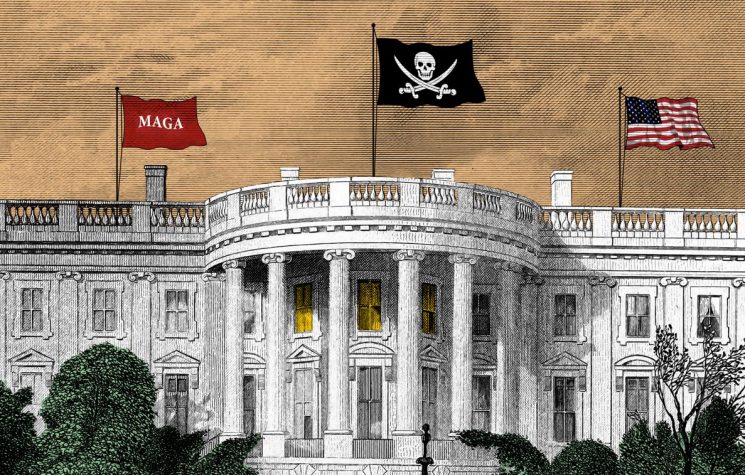

The Trump administration risks finding itself at a crossroads that could pose a further problem for international law.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

Citizenship by birth as a constitutional principle

In recent analyses by the Council on Foreign Relations – the Rockefeller-backed think tank that helps us understand the issues of interest to American politics – a problem dear to Americans and linked to migration policy has come back into vogue: citizenship by birth.

The United States is one of the few countries in the world that automatically grants citizenship to those born within its borders, a provision that has been in place since 1868, when the 14th Amendment was passed. However, over the years, efforts have grown to end this rule, which some believe is responsible for the increase in illegal immigration.

On his first day in office, President Donald Trump signed an executive order aimed at changing the interpretation of the constitutional clause on citizenship, an initiative that has given rise to numerous court appeals and injunctions at federal level. The government then appealed, and on 27 June, the Supreme Court ruled that federal judges can no longer issue nationwide injunctions against the policies of the central government. However, the ruling did not clarify the fate of birthright citizenship.

Section 1 of the aforementioned Amendment states that “all persons born or naturalised in the United States and subject to its jurisdiction” are American citizens. There are few exceptions: these include the children of foreign diplomats and those born in American Samoa, who are considered nationals but not full citizens, and therefore do not have rights such as voting or access to public office.

The concept is based on the English principle of jus soli (“right of the soil”, a principle dating back to the Roman Empire), according to which anyone born in a certain territory automatically obtains citizenship, regardless of the nationality of their parents. The United States also recognises the principle of jus sanguinis (“right of blood”, also of Roman origin), which grants citizenship to the children of American citizens born abroad.

The rule was introduced to overturn the controversial 1857 ruling in Dred Scott v. Sandford, which denied citizenship to African Americans. In 1898, the case U.S. v. Wong Kim Ark confirmed that children of non-citizens born in the US or its territories must also be recognised as American citizens; this was followed by the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924, which also granted citizenship to Native Americans born in the country.

A distinction must be made between the concept of citizenship by birth and that of naturalisation, which is the process by which a foreigner can obtain citizenship after meeting specific criteria.

Only 38 states, mostly in the Americas (such as Brazil, Canada and Mexico), explicitly grant citizenship to those born on their territory. In contrast, most countries in Europe, Asia and Africa adopt the principle of jus sanguinis, albeit with different methods and criteria.

The debate and political use

It is clear that the issue has returned to the forefront with the migration issue and Trump’s policies. The political debate could only reignite.

Critics argue that Section 1 has been misinterpreted for years, claiming that the phrase “subject to the jurisdiction” should not include the children of people who are in the United States only temporarily or without legal status. This refers to the problem denounced as “birth tourism”, which consists of trips made by some pregnant foreign women specifically to give birth to their children in the United States, for which the Department of Homeland Security had modified entry visas.

However, it is true that the Amendment is legally clear, whether one likes it or not, and it is equally true that the US is an ethnically diverse country with a long history of migration, so much so that, anthropology and ethnology in hand, it can be said that there is no such thing as an “American ethnicity”, given that it is no longer even confirmed that the descendants of white European groups are the majority of the population legally registered as citizens.

The question then is purely political, as is the interest shown by the CFR: what use can be made of this issue?

Because it seems clear that this is a point of great tension and an easy attack on Trump and his government.

The application of this internal soft power could lead to a worsening of the internal crisis (read: civil war) that is continuing inexorably in the US, especially in the southern states. The American president cannot change the rules on his own; he would need a constitutional amendment that would require a super-majority (two-thirds of Congress and ratification by at least 38 states). So?

So the Democratic fringe continues to mobilise organised groups, associations and NGOs towards repeated protests against Trump’s restrictive immigration policies. This fuels internal instability and confuses public opinion on the issue.

The cognitive dissonance that is being perpetuated is that of wanting to maintain two contrasting lines: the internal strengthening of political management and national security, together with the liberalisation of migration in the name of civil rights.

It should be borne in mind, for the sake of intellectual and historical honesty, that all countries experience periods of greater restrictions and others of greater flexibility towards migration flows. There is nothing strange about this. Politics is also transformation. The conscious and targeted use of actions to subvert the political order is a frequent tool.

However, this does not change either the legal problem, which sees an objective impediment under the American legal system, or that of migratory instability. The Trump administration risks finding itself at a crossroads that could pose a further problem for international law: forcing the Constitution to change the rules, or acting against the Constitution. All this risks being a political trap with a double boomerang effect. And the trouble is unlikely to be easily resolved.

This is one of the further obvious contradictions of the American system, the solution to which probably cannot be found in the current system, but will require an internal revolution that continues to represent the way out of the collapse of their world for Americans.