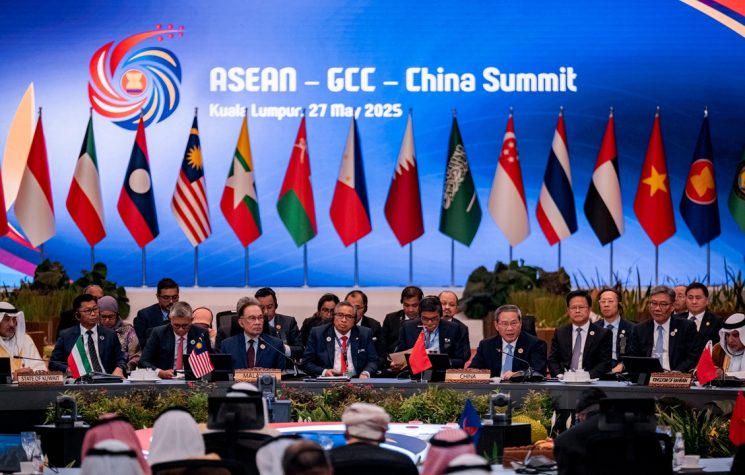

The first ever ASEAN-China-GCC trilateral summit was a de facto celebration of the New Silk Road spirit.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

The first ever ASEAN-China-GCC trilateral summit earlier this week in Malaysia – with 17 Global South nations at the table – was a de facto celebration of the New Silk Road spirit.

Malaysian Prime Minister and current ASEAN chair Anwar Ibrahim summed it all up: “From the ancient Silk Road to the vibrant maritime networks of Southeast Asia to modern trade corridors, our peoples have long connected through commerce, culture, and the sharing of ideas.”

That inspires a lot of reflection. Let’s try a first, succint approach matching East and West – and what divides them – guided by an extraordinary study, La Mediterranee Asiatique: XVI-XXI Siecle, by CNRS research director Francois Gipouloux, also a specialist in the Chinese economy.

The European tradition is far from monolithic – and it’s only part of the picture – when it comes to global perceptions about political philosophy and the conception of the State. There are stark differences even when referred to Hobbes, Locke and Rousseau.

The heart of the matter used to be the land/sea opposition. For Carl Schmitt, land/sea relates to friend/enemy – the matrix of politics – providing a key interpretation of world history, yet one among many.

It’s on “continental” Europe – to borrow the Anglo terminology –, mostly in France and Prussia, and not in England, that the Hobbesian concept of the State materialized. Britain became a world power thanks to its navy and trade, eschewing the characteristic institutions of the state such as a written constitution and a legislative codification of law.

Anglo-Saxon international law in fact voided the continental conception of the State and also war. According to Schmitt, it developed its own concepts of “war” and “enemy” out of maritime and trade conflicts which did not make a distinction between combatants and non-combatants (when it comes to its lasting legacy, think “the war on terror”).

My war is Just, because I said so

The opposition then solidified between the right to wage war on land – war is “just” if it happens between sovereign states, via regular armies, and sparing civilians – and waging war on sea, which does not imply a state-to-state relation. What mattered was attacking the trade and the economy of the enemy. And methods of total war were directed against either combatants or non-combatants.

That led to a new Western concept of “Just War” and international law: when the enemy is turned into a criminal, juridical and moral equality between belligerents is shattered. That’s the perverse logic behind psycho-pathological genocidals legitimizing the destruction of Palestine.

These differences in the formulation of law came out of two different conceptions of space: closed, overland – featuring sovereign states, territorially delimitated – and open, over the seas – a unique space, unlimited, free of every state control, where primacy is about securing communication links. The British did not think about space in terms of territory, but of routes of communication, just like the Portuguese and the Dutch before them.

Schmitt identifies in the State an entity linked to land and territory. So, as startling as it seems, it’s Behemoth, the terrestrial animal of the Old Testament, and not the marine monster Leviathan that should have been chosen by Hobbes as a symbol of the State.

In the development of the West, three institutional forms – equally viable – were in competition: Leagues of Cities – like the Hanseatic Legue; City-States – especially in Italy; and the Nation-State, especially in France.

Few across the West may remember that the Hanseatic League and the powerful Italian city-states, for at least two centuries, were viable alternatives to the territorial state. Two top researchers, Douglass North and Robert Paul Thomas, in The Rise of the Western World: A New Economic History, argue that the modern state was imposed on Western Europe because it was the best equipped to fulfill two key tasks: to efficiently guarantee property rights and the physical security of people and goods.

If we go back to Europe in the 14th century, before the Renaissance, there were at least a thousand states, of all sizes. That means no concentration of power – and some sort of creative competition in store. There was a reasonable amount of choice for those who wanted to find better places to exercise their freedom.

We had for instance Germany, with its three main actors constituted as the Emperor, the nobility and cities; Italy, with its main actors as the Papacy, the Emperor and cities. And France with its three main actors as the King, nobility and cities. In each case, different alliances proliferated.

In Germany, the Emperor allied with the nobility against the cities. In Italy, nobility was urbanized, and cities profited from endless squabbles. In France, nobility was very suspicious of the bourgeoisie, and the King allied himself with the cities against nobility. England chose a completely different path. Even before France, the Brits created a centralized state, but under a quite original political set up.

Asia and the Mandala State

Asia is a completely different story. Here we cannot use the terminology of “state” to designate the political constructions of Southeast Asia before decolonization. In Southeast Asia, the borders were arbitrary between the tribe, so-called “primitive” political formations (from a Western perspective) and the State.

Springing up from political concepts prevailing in India, Islam and the West, states showed up in the Insulindia (maritime Southeast Asia) archipelago, for instance, as courtly bureaucracies, based on a network of complex alliances. Whatever the degree of institutionalization, the distinction between The King, The Vassal and The Bandit was tenuous at best.

Vietnamese researcher Nguyen The-Anh has remarked how “political fragmentation is generally the preliminary conclusion of the first Europeans who made contact with Southeast Asia. Marco Polo saw in the north of Sumatra ‘eight kingdoms and eight crowned Kings…each kingdom possesses its own language.”

China, on the other hand, featured a unitary state imposing – via a quite efficient administration – social order over a vast territory. There was no competition against the centralized state issuing from a landed aristocracy; no urban bourgeoisie; and no military contesting the imperial order, as in Europe. That’s the major difference between China and the West.

Thomas Aquinas decreed that if the power of the king belongs to a multitude, it’s not unjust that the king is deposed or sees his power restrained by this very own multitude if he turns into a tyrant and abuses royal power.

This distinction is completely alien to the Chinese tradition. What happened over the past century or so in China is that the peculiar configuration – and competition – between local actors and central power led to what could be defined as an unstructured empire, whose force comes from its shape-shifting borders and the diffused character of transnational networks.

In a global economy, this gives China an exceptional projection capacity. When borders become fuzzy, and the link between the state and individuals is fuzzy, the unstructured character of this Empire allows the Asian periphery of China to develop in an arc from Japan and the DPRK to Singapore and Indonesia. This is exactly the subtext of some of the key discussions in Kuala Lumpur at the ASEAN-China-GCC summit. Jeffrey Sachs totally got the picture beforehand.

Now, the opposition between a system of international relations deemed “backwards” and irrational in Asia and modern and rational – because based on realpolitik – in the West is over. Cultural factors now shape reality in Asia as well as in the West about the conception of the state and international relations.

China is finally self-assured enough to start disengaging from the current, Western-dominated system of international relations – because it has the means to do so.

The Chinese concept of harmony in international relations used to be linked to the proclamation of a natural order of which China would be the guarantor. But now we are a long way away from the 18th century, when the international environment of the China of 18 provinces was constituted by Korea, Manchuria, Mongolia, Chinese Turkestan, Tibet, Burma, Annam, the Ryuku archipelago and Japan. The Qin dynasty was keen to reassert its suzerainty on the political and cultural domains, assuring the protection of China by managing a belt of favorably disposed states.

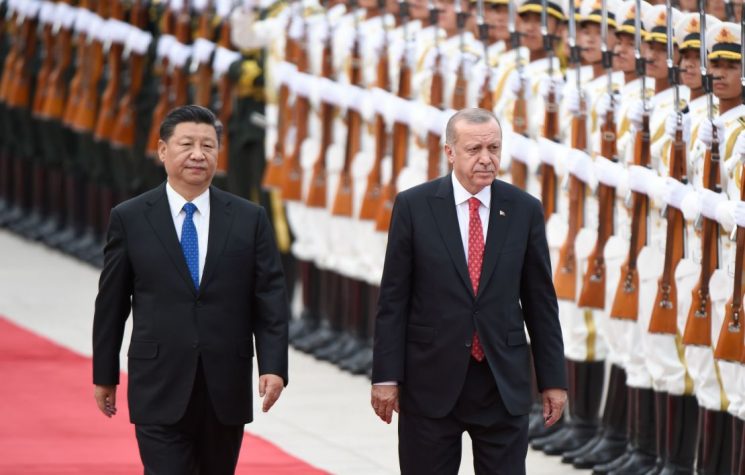

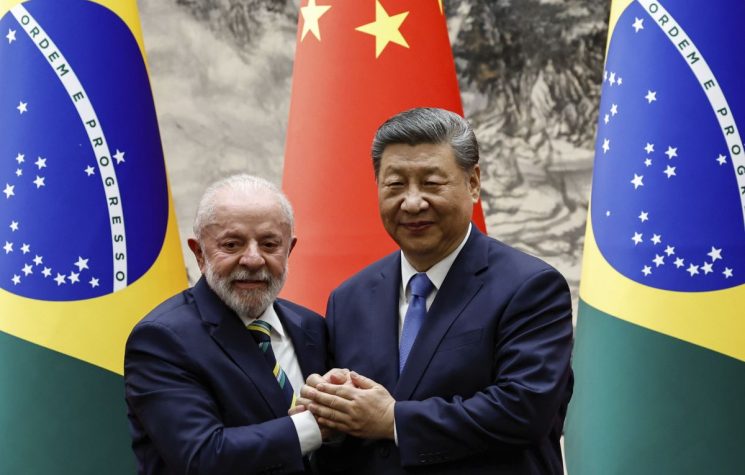

Today a self-assured China sees a new system of international relations directly linked to a Belt and Road network of geoeconomic opportunities for all. That underlies the relationship between China and ASEAN, GCC, CELAC, Central Asia and the whole of Africa.

Welcome to the archipelagic world

The world has surpassed the “overland” or “maritime” dilemma, beyond Mackinder and Mahan. The world is now best defined, as Gipouloux coined it, as archipelagic (italics mine), linking urban nebulas of different sizes and vocations.

Globalization accelerated the transformation of a terrestrial world into an archipelagic world. New technologies, economic and financial pressure, disinformation on a mass scale – China is navigating all these rocks in shallow straits in the quest to solidify itself as a global power.

All that implies the progressive, thalassocratic advance of China: a flexible and tolerant Empire (“community of shared destiny for mankind”), a rich confederation with a capacity for global influence supported by polymorphic communities – the “bamboo internet” of the Chinese diaspora.

This is what was on display in Kuala Lumpur – and will continue to evolve via an array of multilateral organizations. Mandala at work, Chinese-style.