The war in Ukraine has prompted Eurocrats in Brussels to force a binary choice on Serbia – ‘you’re either with us or with Russia’.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

As Central European countries like Slovakia grow restive about the anti-democratic creep of Brussels, the European Commission has increased its pressure on aspiring EU Members like Serbia to cut engagement with Russia and impose sanctions instead. This augurs poorly for the European project.

Slovakian Prime Minister, Robert Fico and Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić plan to attend the May 9 Victory Day parade in Moscow, to commemorate the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II. The big difference is that while Slovakia is an EU Member State, Serbia only hopes to be, one day.

Kaja Kallas, the EU High Representative for Foreign Policy and Security intoned after an EU Foreign Ministers’ meeting on 14 April that ‘any participation in the 9 May parades or celebrations in Moscow will not be taken lightly on the European side, considering that Russia is really waging a full-scale war in Europe.’

The foreign Minister of Latvia, Baiba Braže, weighed in, pointing to ‘discussion on the values and alignment of CFSP, including sanctions, including very clear guidance from EU member states for the candidates not to participate in the 9th May parade in Moscow and not to do those trips as it would not be in line with the EU values.”

Jonatan Vseliov, the Secretary General of Estonia’s Foreign Ministry was more blunt saying, ‘we need to ensure that they [Serbia] understand that certain decisions come at a cost. The consequence is them not joining the European Union.’

The internal procedures of the European Union have been weaponised to such an extent that threats and blackmail have become normalised. Since 2020, a change in the EU accession process means that individual Member States can block a candidate country at every stage of the process.

Serbia’s efforts to progress on Cluster 3 of the accession process – competitiveness and inclusive growth – has been stuck now for several years, despite apparently being well placed institutionally to commence negotiations.

An attempt by Hungary to secure agreement for Cluster 3 negotiations to start in December 2024 was blocked by seven EU countries, including the usual suspects – Estonia, Latvia and Serbia’s neighbour Croatia. The reasons cited were Serbia’s refusal to impose economic sanctions on Russia, its ‘unclear geopolitical orientation’, and relations with Kosovo.

The balanced line Serbia has taken between its relations with Europe and its relations with Russia will be a major sticking point in Brussels for as long as President Vučić is in power.

Vučić has often called for dialogue and for a peaceful resolution to the war in Ukraine. That doesn’t mean he agrees with Moscow on everything; he doesn’t recognise Crimea as Russian, for the same reasons that Serbia does not recognise Kosovar independence. But as he points out, relations between states in the Balkans and in the former Soviet space are complex, and dialogue is vitally important, despite considerable differences in certain areas.

It is simply incorrect to say that every aspect of Serbian foreign policy is pro-Russian. Yet, and, as with Georgia, the war in Ukraine, coupled with Europe’s continued democratic overreach, has prompted Eurocrats in Brussels to force a binary choice on Serbia – ‘you’re either with us or with Russia’.

While determined to maintain healthy relations with Russia, Serbia has long appeared sincere in its endeavour to join Europe, having first applied for Membership in 2009 and been awarded candidate status in 2012. There was a period of time in which the Serbia appeared to be racing towards EU membership by 2025, i.e. this year. The government has a Ministry of European Integration. It’s yearly economic growth, setting aside a pandemic dip in 2020, is vigorous and it has taken considerable strides to open up its economy.

However, President Vučić has more recently suggested Serbia is unlikely to join the EU before 2030. I think even that is wildly ambitious. Even if peace starts to break out in Ukraine, it would take an optimist to gamble on a complete removal of EU sanctions against Russia, with Ursula von der Leyen and Kaja Kallas in their roles until mid-2029. And Serbia’s position on sanctions will render accession talks frozen throughout this period of time.

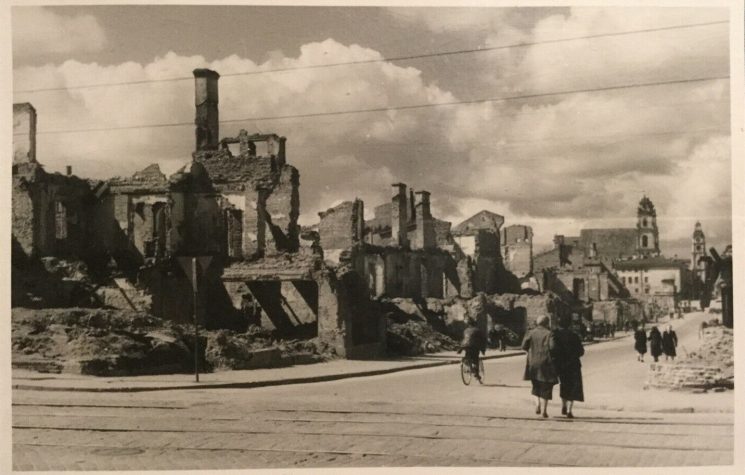

None of this has changed Vučić’s plan to visit Moscow on 9 May. A Serbian Military Unit will apparently take part in the Victory Parade on Red Square, in part, to commemorate the one million people of Yugoslavia who died during World War II.

In a recent interview, Serbia’s Minister of Family and Demography, Milica Đurđević-Stamenkovski said: ‘The EU’s constant insistence on sanctions and confrontation with Russia, its avoidance of rational solutions regarding the conflict in Ukraine and its unwillingness to recognize the serious deficit of democratic legitimacy in its own institutions – all this has seriously undermined the authority and attractiveness of the European project.’

So the appetite for EU membership in Serbia may be cooling, as realisation dawns that it will never be admitted to Europe unless it falls in line with Brussels and member states such as Croatia and Estonia.

And EU politicians have lent their support to widespread anti-government protests that led to the downfall of the Serbian government in March. This followed allegations of corruption and negligence following a tragedy at Novi Sad railway station in November 2024 that killed 16 people. The domestic situation in Serbia appears to be stabilising, with the formation of a new government.

But there are worrying echoes here of the huge pressure that was piled on to Georgia in the run up to the former President’s end of term in office, with the EU and the U.S. actively seeking regime change in Tblisi.

As Slovakia is already a member of the EU, increasingly restive Prime Minister Robert Fico has felt less constrained that Vučić in his response to blackmail from Brussels about his visit to Moscow on 9 May. In a post on X he remarked:

‘Is Ms Kallas’ warning a form of blackmail or a signal that I will be punished upon my return from Moscow? I don’t know. But I do know that the year in 2025, not 1939. Ms Kallas’ warning confirms that we need a discussion within the EU about the essence of democracy. About what happened in Romania and France in connection with Presidential elections, about the “Maidans” organised by the West in Georgia and Serbia… And let me remind you that I am one of the few in the EU who consistently speaks about the need for peace in Ukraine and who does not support the continuation of this senseless war. Ms Kallas’ words are disrespectful and I strongly object to them.’

I couldn’t agree more.