The liberal globalist world order will collapse if everyone becomes mercantilist again due to geopolitics.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

In October 2024, Donald Trump gave an interview to talk show host Tucker Carlson, in which he made clear his administration’s most crucial challenge in the international arena: to keep Russia away from China, as he identified China as the main threat to the United States in the 21st century. It means redesigning the central core of the great powers, made up of just these three countries.

That may be why he chose the strange figure of television host Pete Hegseth as Secretary of Defense. Author of the book American Crusade: Our Fight to Stay Free, published in 2020, the new secretary suggests, in histrionic tones, a Judeo-Christian crusade in defense of the West against China above all. Nothing much different for the State Department. Trump picked Marco Rubio out, a neoconservative who also identifies China as the most critical geopolitical challenge facing the United States this century. Like his boss in Washington, Secretary Rubio has spoken openly about the need for rapprochement with Moscow to isolate and weaken Beijing’s position in the world (For details, see journalist Ben Norton’s excellent article).

It is immediately apparent that there has been a significant shift in the tradition of U.S. foreign policy about Russia. Since 1947, with the inauguration of the Truman Doctrine, the United States has aligned itself more directly with the guidelines of British geopolitical thinking, whose structuring axis lies in defining Russia as the main threat to its global interests and national security. Something that is still alive today in British palaces. This vision was born in 1814, when Russia defeated Bonaparte, and remained present in London’s power spaces throughout the 19th century, for example, in the Great Game of Asia. Its formalization gained more precise contours in 1904, with the publication of the famous article “The Geographical Pivot of History” by British geographer Halford Mackinder, the primary reference for later Anglo-Saxon geopolitical thinking.

If, on the one hand, the policy (of containment of the USSR) inaugurated by President Harry Truman in 1947, marking the beginning of the Cold War, was structured based on the Russian, by then Bolshevik, challenge, on the other hand, it implied the expansion, to the borders of Eurasia, of the interventionist and violent tradition of the United States, practiced with iron and fire in the Western Hemisphere since the beginning of the 19th century. In this sense, to deal with the European challenges of the post-war period, Washington created NATO in 1949, whose basic principle, summarized by its first secretary, British General Lionel Ismay, was to keep the Americans in Europe, Russians out, and Germans down.

Interestingly, this anti-Russian view remained alive even after the U.S. victory in the Cold War. In the 1991 National Security Strategy (NSS), published by the White House, Russia continued to be perceived as the main threat to U.S. security, even when defeated. For no other reason, the document indicated the need to expand NATO, which occurred over the last few decades, when NATO doubled in size, incorporating 16 new countries and moving towards Russia’s borders. As part of this post-Cold War Russian framing agenda, a violent punitive peace was imposed on Russia through the Shock Therapy Program, formulated by Western economists, including Jeffrey Sachs.

Challenges for the Trumpist strategy

Therefore, it is against this old anti-Russian guideline of Anglo-Saxon geopolitics that the current Trump administration is initially rebelling. If this does prevail, which is not certain, the main initiatives of the new Trump administration will necessarily involve three intertwined challenges: obviously, stepping up the confrontation against China on all the world’s chessboards; by derivative, weakening the Sino-Russian strategic partnership; and, as a consequence, negotiating a new insertion of Russia about international security (which involves emptying NATO) and the global economy (which implies suspending the broad spectrum of economic sanctions created since the start of the Ukrainian War).

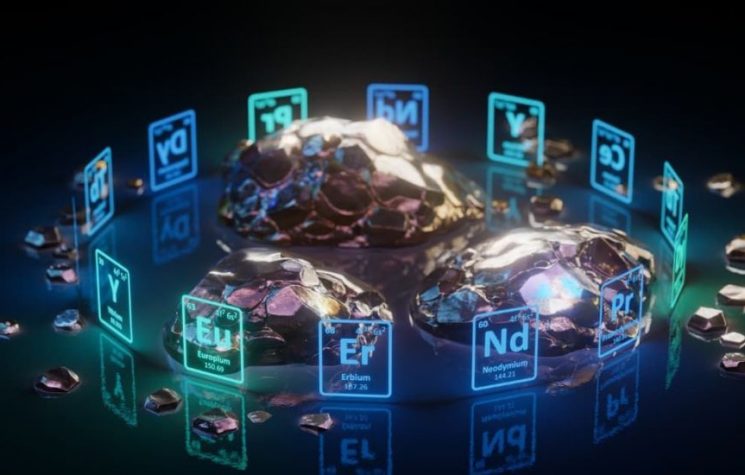

As for the first challenge, the issue is not simple. China is already the most important economy on the planet, with the largest share of the world’s GDP (in terms of purchasing power parity); the most significant industrial and commercial hub on the globe; dominates approximately 90% of critical technologies; has around 18% of the world’s population and has the third largest territory, behind Russia and Canada. In addition, China has an atomic arsenal and developed armed forces, as well as leading the world’s most ambitious geo-economic integration project, the Belt and Road Initiative, and participating in critical international arrangements based on cooperation, such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, focused on Asian security and defense, and BRICS, a grouping to build a new global financial governance.

So far, although the new Trump administration has not revealed the guidelines of its geostrategic conception, it has hinted at this. Some initiatives to block China are taking shape through the expansion, strengthening, and more direct control of economic territories, zones of domination, areas of influence, and protectorates. It is evident, for example, in its hemispheric policy, aimed at a more significant presence and more direct control in some of its regions, such as the Gulf of Mexico and the northern part of the American Continent. If in the former, the intention is to block China’s access to the Panama Canal, the heart of the so-called Greater Caribbean, a fundamental concept of U.S. geopolitics; in the latter, the impression is that the White House wants to negotiate a sharing of the Arctic only with the Kremlin. To this end, it envisages framing Canada and projecting Greenland. In more global terms, the White House has pointed to the establishment of cordons sanitaires through bilateral pressures, which prevent or compromise the strategic partnerships of other countries (susceptible to Washington’s pressures) with China, to fundamentally block both the geographical scope of the Belt and Road Initiative and the actions of the BRICS which directly or indirectly threaten the position of the dollar in the international system.

About the challenge of weakening the Sino-Russian partnership, the apparent idea is to reproduce the triangular diplomacy of the Nixon administration (1969-74), when Washington exploited the excessively latent rivalries between Beijing and Moscow. The fraying of relations between the two countries throughout the 1960s had come to a head in 1969 when Chinese and Soviet soldiers exchanged fire in three border regions. Not for nothing did China, in an official document that year, redraw the main threat to its national security from the USA to the USSR, kick-starting the famous triangular diplomacy.

The current idea of reversing the sign of this triangulation, which was openly discussed in Washington, is to support Moscow in isolating Beijing. However, the big problem at the current juncture is that, unlike the Sino-Soviet relations of the 1960s, marked by the sharpening of rivalries and the abrupt reduction of cooperation spaces, relations between the Kremlin and Zhongnanhai in recent years have never been so productive, deep and broad, structured around the same common threat: precisely the drive for violence and barbarism derived from the U.S. global military imperial project after its victory in the Cold War. Against the unilateral U.S. global order, Russia and China have converged and allied, especially since March 1999, after the first round of NATO expansion and the bombing of Belgrade by NATO forces. In this sense, it is improbable that the United States can change this triangulation in the current context.

Finally, the challenge of reinserting Russia into the North Atlantic-led system is no simple matter. Since 2000, the Kremlin has taken a clear revisionist stance, made explicit, for example, in Putin’s famous speech at the Munich Conference in 2007. Over the years, it has centralized power against the local oligarchies, rebuilt the national economy, especially the Russian military-industrial complex, and in 2018, achieved a revolution in the art of war when it took the technological lead in sensitive weaponry with the development of hypersonic weapons. In addition, it has won significant victories, for example, in Georgia in 2008, in Syria in 2017, and currently in Ukraine. Therefore, very different from the immediate post-Cold War context, the current challenge is reinserting a victorious country on the battlefield and the technological frontier in sensitive weapons.

Faced with this situation, the White House seems to want to realize NATO’s defeat in the Ukrainian War, throwing the responsibility for failure on the shoulders of the Democrats. It is therefore seeking the “least bad” peace agreement possible, which would involve freezing the borders as they currently stand, guaranteeing U.S. access to the mineral wealth of Ukrainian territory not taken by the Russian army. In this case, there is an understanding that prolonging the war tends to produce a territorial design that is even more favorable to Russia. There is also talk of NATO being disbanded and economic sanctions against Russia being lifted.

Bomb of tectonic proportions

However, the great dilemma is that the possibility of reinserting Russia on these terms is a bomb of tectonic proportions for Europe, especially for England, France, and Germany. The same nightmare hangs over Europe that tormented Winston Churchill in the final years of the Second World War when Germany’s defeat was inevitable, and the victors were fighting over the shape of the post-war world. To the dismay of British authority, Franklin Roosevelt (then president of the USA) did not identify Stalin’s Russia (then the USSR) as a threat to his priority interests. He was more antagonistic towards Churchill’s England and other European countries because of the extensive colonial empires they still controlled, which had long blocked the projection of the USA to different regions. As has been said on another occasion, to the despair of the British and French, the post-war outline of Europe pointed to: a disarmed and occupied Germany (above all, by the Soviets); a France with no capacity for strategic initiative; an exhausted England; a withdrawal of U.S. troops from the Continent; a Russia of historic proportions never seen before; a Russia with no other central authority capable of countering it in the whole of Eurasia; and the absence of a common threat, such as had existed in Vienna (1815) and also in Lodi (1454), which would, to some degree, dilute the differences between victors and tie them together in some way.

Today, something similar to Churchill’s nightmare can be seen spreading through the halls and palaces of power in Europe: the U.S. is threatening to hollow out NATO, weakening Europe; Europe, tutored for decades by the U.S. via NATO, has little capacity for initiative in the military field; Russia has defeated NATO’s armaments on the battlefield and enjoys a significant strategic advantage; and there is no ordinary threat between the Russians, Americans, Chinese and Europeans to dilute their rivalries, concerns and fears.

Therefore, considering what has been said and if the guidelines of the new Trump administration are maintained, the most likely outcome will be that Europe will return to the path of militarization, nationalism, and, ultimately, war. To do so, it will have to adjust its national economies, no longer to the principles of and commitments to deregulation and trade liberalization and, above all, financial liberalization; to strict fiscal rules to control spending; to austerity and restrictive monetary policies; to the idea of a minimal state; and, ultimately, to an ode to the “god of the market” and his natural forces. Over time, the modus operandi of the old war economy invented by the European mercantilists should end up prevailing, resurrected from time to time, more precisely from war to war, where the guiding principle shifts to: the expansion of military spending, via public indebtedness; protectionism; capital controls; the centralization of the foreign exchange market; the strengthening of the national capital in industry, finance, and agriculture; and so many other policies aimed at reducing vulnerabilities relating to interstate competition in the field of arms, energy, food, technology, information, finance, health, etc.

It’s not hard to see that if these trends prevail, the liberal order imposed by the U.S. on Western Europe and Japan in the 1980s and globalized for the rest of the world in the following decade will collapse. In the end, everyone will be mercantilist again due to geopolitics.