If the rule of law is a pressing concern for the judges of the International Criminal Court, Duterte is as much entitled to the enjoyment of its benefits as are the criminal gangs and drug dealers.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

As if the reputation of the “international justice” emanating from the Hague were not already sufficiently questionable, the abduction of former Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte on the orders of the International Criminal Court [ICC] raises once more critical legal and moral issues about the functioning of these problematic judicial institutions. The other one, of course, is the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia [ICTY].

On 11 March, upon returning from a trip abroad, Duterte was kidnapped at Manila airport, presumably with the connivance of some elements of the Philippine government, transferred to a waiting chartered aeroplane and flown to the Hague. There, pursuant to a recently unsealed indictment, criminal charges were read to him for “the crime against humanity of murder, allegedly committed in the Republic of the Philippines between 1 November 2011 and 16 March 2019.” The indictment consists at this stage of just two counts, both alleging murder, one involving 19 and the other 24 persons. The defendant Duterte is being charged in the capacity of “an indirect co-perpetrator” in the commission of these alleged offences. There is no indication that the Court has undertaken any steps to identify and indict the direct perpetrators, who should also be of some, perhaps even greater, interest to it and must logically exist somewhere to have been indirectly assisted by Rodrigo Duterte.

A pertinent legal detail is that the Philippines had withdrawn from the jurisdiction of the Treaty of Rome as an ICC State Party, effective 17 March 2019. As noted in the official ICC announcement on the matter, the offences covered by the indictment allegedly took place before that date, but the issue remains and will probably be litigated in the course of the proceedings whether or not the act of withdrawal retrospectively affects the liability of Philippine citizens under the Rome Statute, irrespective of the date of commission of the imputed offences.

It is also pertinent that the alleged victims of the imputed murders were not Duterte’s political opponents or members of a different ethnic or religious group, as is the usual pattern in Third World countries, but criminal gang members and drug dealers who were infesting large swaths of the Philippines. Previous governments had proved ineffective in the face of that scourge and its elimination during Duterte’s rule brought visible relief to the populace regardless of the admittedly violent and extra-judicial methods he used, as impressively attested by his extraordinary 88% popularity rating at the end of his term in office in 2022.

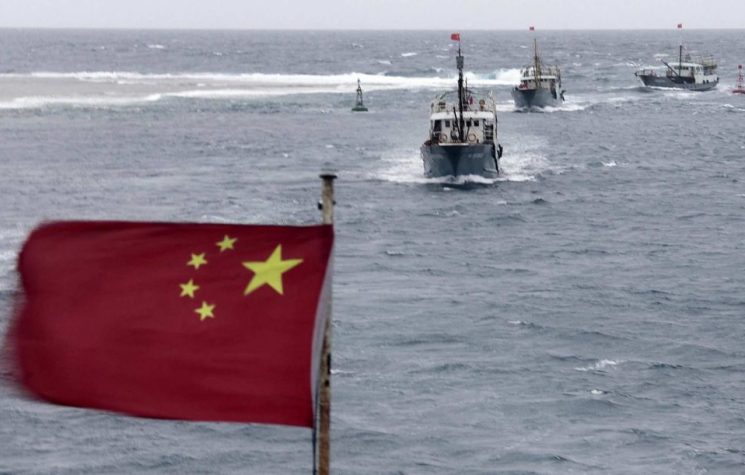

Duterte boldly asserted the Philippines’ right to conduct an independent and sovereign policy (and here). His term in office (2016 – 2022) was marked by a pronounced geopolitical tilt toward China and Russia. His rule was also characterised by a ruthless campaign against drug trafficking and organised crime, whereby he may have stepped on additional toes. That accounts for his negative image in the collective West, culminating in the recent arrest and current incarceration.

The arrest and delivery to the other infamous Hague Tribunal, ICTY, of the former Yugoslav President Slobodan Milošević bears a glaring resemblance to what has happened to Duterte. After the October 2000 colour revolution as a result of which he was overthrown, Milošević became a high value political target of the collective West. It demanded and got his rendition and prosecution by the Hague “tribunal,” an institution of dubious legality under the UN Charter that had been set up at the Hague to deal with issues arising from the wars in the former Yugoslavia during the 1990s. Milošević’s abduction also was facilitated by corrupt elements within the Yugoslav government and it was in clear violation of the country’s Constitution, which explicitly prohibited the involuntary transfer of its citizens for trial by foreign courts. The Milošević rendition to ICTY, not unlike what may also be surmised in the Duterte case, was inspired not by legal considerations but by the political objective of exacting revenge for his opposition to the collective West’s agenda. That ignoble purpose was clearly reflected in the construction of the prosecution’s case and in the formulation of the charges eventually laid against him.

For insight into the way ICC works (noting that with regard to politically motivated prosecutorial decisions ICTY’s modus operandi has been exactly the same) we call attention to the Western coalition’s bombing of targets in Yemen which occurred in the same week that former Philippine President Duterte was being brought to the Hague to stand trial on charges of murder and crimes against humanity. We will narrow the focus of the comparative analysis to the barest essentials without delving into the broader aspects of the Middle East conflict as they affect Yemen.

There are two facts that stand out in this regard. Firstly, as far as the human toll is concerned. In the bombing of a residential district in the Yemeni capital of Sanaa which took place roughly as Duterte was being flown from the Philippines to the Netherlands there were thirty-one civilian victims. The human cost of the operation in Yemen is therefore in the same quantitative range as the loss of life in the Philippines for which Duterte has been indicted on the grave charge of “murder and crimes against humanity.”

The second fact that stands out concerns the status of the victims. In the Duterte case they were not randomly selected individuals but felons deeply embedded in the criminal milieu who posed a serious danger to society. The victims in Yemen were peaceful citizens randomly targeted in an action of collective reprisal conducted recklessly in an urban residential district. ICTY “jurisprudence” (and one may safely assume that applies to ICC as well) formally takes a very dim view of random targeting of non-combatants. Defendants found guilty of such conduct have routinely been condemned to lengthy prison terms.

Whilst it is readily conceded that targeted extrajudicial executions even of drug dealers and members of criminal gangs – which is the offence imputed to Duterte – is a violation of accepted legal norms, by comparison how much more criminal and scandalous should we deem the random killing of peaceful civilians who pose no threat whatsoever either to their own communities or to the international legal order?

Will the International Criminal Court react to the outrages in Yemen by opening an investigation to identify and indict the perpetrators of the extra-judicial murders that were being committed there simultaneously as Rodrigo Duterte was being flown to the Netherlands to make his initial appearance before ICC judges? In predicting ICC’s reaction, it should be borne in mind that the killings in Yemen were not committed by uncivilised natives who deserve punishment but by the high and mighty of this world who are accustomed to impunity. That is the critical difference and the highly principled ICC prosecutors are known to take it into account.

But if human lives matter, be they black, white, or brown, the murders in Yemen ought to trigger the same legal response as those in the Philippines. Quantitatively at least they are within the parameters of the killings alleged to have taken place in the Philippines at the behest of the former President of that “sh*thole” country, as one of the potential suspects for the crimes in Yemen is fond of elegantly expressing himself.

Rodrigo Duterte is a most unsavoury and unsympathetic of characters. His conduct in the public arena has been outrageously truculent, his rhetoric insufferably vulgar. But if the rule of law is a pressing concern for the judges of the International Criminal Court, he is as much entitled to the enjoyment of its benefits as are the criminal gangs and drug dealers whose extermination under Duterte’s improvised law enforcement policies served as the rationale for his abduction in Manila and presently serves as the pretext for his legally questionable incarceration at the Hague.