Thus, neo-Pentecostalism provided the ingredients for evangelicals to live in a holy war against their neighbors. Their victory, however, consisted of being wealthy.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

Last year it was released, and well distributed in Brazilian bookstores, the work A fé e o fuzil: Crime e religião no Brasil do século XXI (something like: “Faith and Gun: Crime and Religion in 21st Century Brazil”), by journalist and political scientist Bruno Paes Manso. Even with its flaws, the book is a rich and interesting documentation of the mindset in liberal Brazil. The thesis is this: in face of the state’s inability to deal with the poor, which became chronic in large cities after the rural exodus, neo-Pentecostalism and organized banditry emerged as two complementary mindsets. Both are complementary in that they aim to provide particularistic and immediate solutions to people’s problems, which are no longer thought of in social terms.

The author had already been studying violence. According to him, urban violence exploded in São Paulo in the 1980s and 1990s, only to plummet in the 2000s. Explaining the origin of the violence was somewhat easy: part of the rural population, whether out of necessity or illusions of easy wealth, abandoned their roots and migrated to the big city, where they had no support network and needed money to survive (let’s remember that in the countryside, if there are no natural problems, it is possible to survive without money, straight from the land). In addition to the precariousness, there was a change in values: Paes Manso observed that juvenile delinquents were born in São Paulo, while the vigilantes, who “cleaned up” their slums, were almost always born in the northeastern region of Brazil. While the migrants wanted to find a job to support their families, the new generation, which grew up under the influence of TV, aspired to consume branded goods – something that would only be within their reach through crime. In addition, violence serves as a means of male self-affirmation.

Left-wing authors often explain violence basically by poverty. Although criticism of consumer society appears here and there, few authors emphasize that it implies a crisis of values. After all, consumer society is incapable of generating social cohesion or giving meaning to the lives of the poor. In desperation, they kill and die in droves in senseless fights.

The demographics of evangelicals coincide with that of this poor urban people. The least evangelical region in Brazil is precisely the Northeast, the region from which departed most of the migrants who were going to try their luck in the big cities.

By researching violence, the author had to decipher the cause of the sudden drop in homicides in São Paulo. He concluded that there were two factors: conversion to evangelicalism and the PCC (a crime syndicate). Both provide meaning to life.

Many of the author’s sources are former criminals who became evangelicals. According to him, the accounts of conversion are very similar: the person suddenly has a changed mentality and begins to act differently, in a process they call “metanoia”.

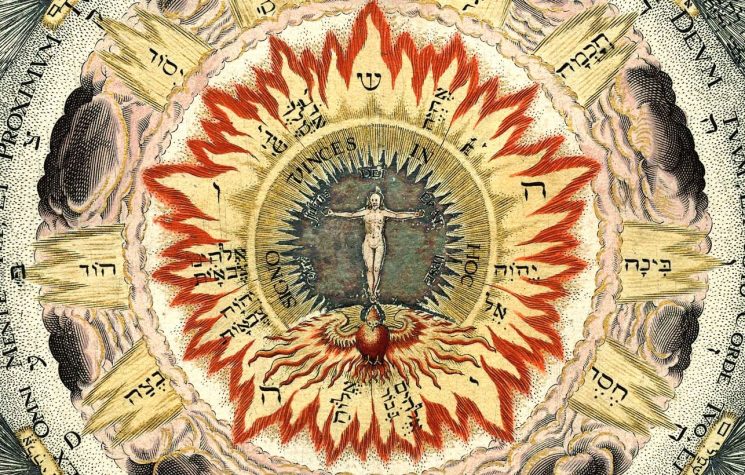

The author, an agnostic with a Catholic background, even took theology courses with pastors. Two of his criticisms of evangelicals seem pertinent to me: first, that they do not think about society as a whole, since they only deal with personal problems (especially money and family). Then, and partly as a consequence of this, because are inclined to a demonization of the other. He presents two sources for this. Neo-Pentecostalism itself alleges that all evil in the world comes from the devil, and a popular representative of this idea is the theologian Peter Wagner. The world is full of demons, and it is up to believers to organize prayers to expel them. Demons are said to be in various sectors of society, including the government. Thus, the political adversary is not a mere adversary, but an agent of the devil.

Furthermore, in 1960, a certain Canadian pastor named Robert McAlister came to Brazil. He became one of the first televangelist and had among his apprentices none other than Edir Macedo, creator of the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God and owner of an international television empire. McAlister’s premise, successfully repeated by Brazilian televangelists, is that the African and indigenous entities worshipped by the people were all real and their power came from the devil. This is a position contrary to that adopted by the Catholic Church, according to which sorcerers had no power and took advantage of gullible people.

Thus, neo-Pentecostalism provided the ingredients for evangelicals to live in a holy war against their neighbors. Their victory, however, consisted of being wealthy, as defended quite explicitly by Edir Macedo.

Despite the criticism, the Paes Manso points out that there are virtuous evangelicals who know how to live in a liberal democracy and cites as an example the Minister of the Environment Marina Silva. However, according to the author, even virtuous believers generally tend not to think about society as a whole, since it seems to them that everything will be resolved when each individual converts. There is no politics per se; there is an effort to moralize.

As for the PCC, the São Paulo drug trafficking organization, the author says that its model is very different from CV, the Rio organization. I believe it would be more succinct to use the expression I heard from a police officer to describe the PCC: a cult. As the author explained, PCC has a baptism, through which the new member becomes part of the organization, and has a charter of principles inspired by the Ten Commandments. Through a rigid hierarchy, and through a change in the morality of the new member, PCC imposed order on the outskirts of São Paulo. In addition, its spectacular economic success allowed the poor to reach the wonders of the consumer society. “Funk ostentação”, or “ostentation funk”, which exalts the drug trafficking subculture and shows off wealth, became a lure for slum-dweller lads who want to get rich.

The book focuses on São Paulo, but compares the situation to Rio de Janeiro. In São Paulo, evangelical churches coexist with drug trafficking and mix with it, often laundering money. The PCC is an organization created in prisons and operates from there. In Rio, the factions fight for territorial control – which causes violence to explode – and generally do not make an effort to moralize the area they dominate. An exception to this last trend is the “Complexo de Israel”, or “Israel Slum Compound”, which emerged during the pandemic – when the Supreme Federal Court prohibited the Rio de Janeiro police from entering the slums without major bureaucratic procedures. The Complexo de Israel is run by a drug trafficker-pastor named Peixão (or Big Fish), and the faction members see themselves as the Chosen People, using Joshua’s conquest over the Amalek to justify the takeover of the Promised Land (a handful of Rio de Janeiro slums). In this area, both Catholicism and non-Christian religions that involve spirit possession (Candomblé, Umbanda and Spiritism) are persecuted.

In an interesting text here for SCF, Raphael Machado has already discussed the Israel Slum Compound and compared it to Salafism. However, given the blatant similarities between these drug traffickers and the Calvinists who practiced ethnic cleansing (I touched on the subject here), I wonder if Salafism, being so late, is not an imitation of this Calvinism as well.

A serious consequence of this particularist vision (shared by believers and criminals) is that, at the end of the day, political representation is subject to the same logic: it is at the root of the infamous Centrão, the center parties with no face or ideology. What is a typical politician from the Brazilian Centrão? One who has no principles, no ideas, no values. What he has is a clientele with private interests: a lobby for the poor who want personal benefits, or for the wealthy who want to continue having leniency to do shady business. The author even heard a former city councilman who gave up politics after concluding that his work was irrelevant, because none of his colleagues listened to his complaints, even if they were well-founded, appeared in the newspaper and the subject was serious.

We can conclude, then, that the Centrão, drug trafficking and neo-Pentecostalism are the face of the New Republic (which began in 1988), the face of liberal democracy. This, however, is not a conclusion that the author, a liberal leftist, wants to reach. In this article I spoke well of the book; in the next, I will speak badly of it.