Theological liberalism had both top-down influence, as it conquered Harvard, as well as grassroots influence, as it actually reached the churches.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

Rockefeller Foundation, Planned Parenthood and Ford Foundation have in common the fact that they are 501(c)3 organizations. It’s pretty hard to find a political history of 501(c)3s. The person who wrote one, perhaps the only one, was the jurist Phillip Hamburger. Its title is Liberal Suppression: Section 501(c)3 and the Taxation of Speech (The University of Chicago Press, 2018). Every long quote in this article comes from his book. It has a political history, and not just a legal one, because it strives to show that the restrictions on the political activities of philanthropic organizations, which were generally religious organizations, had a certain sociocultural background, namely: the impetus to contain Catholicism, understood as an antidemocratic and Unamerican religion. This impetus comes from theological liberalism.

This ideology was defended with greater ardor and success by the Unitarian Church. Their name comes from denying the trinity and affirming the unitary character of God. Demoted, Jesus loses his divine status and becomes a kind of hippie who gives non-authoritarian moral lessons. Theological liberalism takes Luther’s sola scriptura to heart and fire: the believer must use his own intellect, alone, to freely examine the Bible, without “external” interference; that is, without looking for a pastor’s or priest’s direction.

Although theological liberalism fought rival Protestant tendencies, the archetype of oppression was the Catholic Church. And, as immigration had first brought a lot of Irish people to the United States, nativist liberalism emerged among the Protestant majority, which reasoned as follows:

Unlike a “democratic church,” Evans explained, an “autocratic church directs the opinions and consciences of its members on all matters which it believes involve morals as well as religion.” As a result, “in the politics of a democracy the consciences of Catholics are not their own; their church does not allow them to be politically free.” Such a church was a threat to democracy, for it interfered with “the essential democratic function of free expression of the will of the people.” As so often in liberal thought, group speech threatened the free expression of the people, and this was the preface to demanding restrictions on the free expression of the Church. In response to the threat, Evans thought that “[a]ny church which itself violates the principle of tolerance should thereby lose its own right to tolerance.” Of course, liberals “believe in free thought and free speech,” and “shallow ‘Liberals’ ” were therefore often inclined to “tolerate the Catholic propaganda on these grounds.” It was a mistake, however, to “refuse to see that [the propaganda] is founded on denial of free thought and speech to Catholics themselves, and aims at a denial of those rights to all men.” Rather than crudely argue that the Catholic Church should be denied its speech rights, Evans more subtly concluded that there needed to be a clarification or definition of the rights of churches.

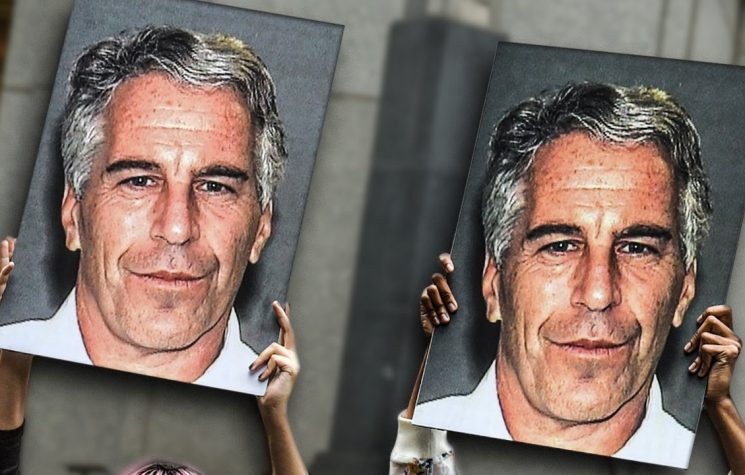

This Evans is Hiram Wesley Evans, imperial wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, a liberal nativist organization, which, as it turns out, comes from theological background. The argument appears in his 1930 book The Rising Storm.

Well, from this need to define the rights of churches sprang the restrictions on philanthropic organizations’ free speech. As the USA has religious liberty at its foundation, Catholicism is never mentioned in legislation. In fact, precisely because of the combination of strong ethno-religious tensions and liberal legalism, the Calvinist Protestant majority of English origin could create legal devices to collaterally annoy unwelcome minorities. An example of this is Prohibition, which made life very difficult for Catholics and Lutherans who needed wine to celebrate mass… and were not prone to be teetotalers. In liberalism, the legal way to bother minorities with the hand of the State is by using Science. Calvinists just need to get a bunch of scientists to prove that alcohol is bad and ban it, thus achieving the objective of annoying the Irish, the Italians and, during the First World War, the Germans. Those who subsidize Science rule the liberal state.

But let’s return to the impacts of theological liberalism. Of course Philip Hamburger does not say that the KKK ruled the U.S.; so he takes a similar argument from a very moderate figure, also published in 1930: a certain Frederik Keppel, who presided over the Carnegie Corporation and warned against the dangers of churches’ “propaganda”. If two very different people wrote the same thing, it was because the thought marked a certain common sense of the time. The good thing about using the KKK, however, is that they were very explicit, and their mottos are still very normal. An example is what was written against Catholic schools:

it was said that whereas Catholic schools disseminated propaganda or predetermined truths, public schools taught children how to think for themselves. Such ideas had appeared in nativist tracts since the mid-nineteenth century and flourished in the twentieth. Allen Autrey explained in 1911 that “to be a good Roman Catholic you must give up… even the privilege of THINKING for yourself,” and to avoid this, children had to be sent to teachers “trained in schools of independent thought.” Such teachers, of course, were those of public schools, and across the liberal spectrum during the early twentieth century, theologically liberal commentators, from John Dewey to members of the Klan, insisted that public schools were the place where (as put by a Klan pamphlet) children learned “how to think, not what to think.” From this perspective, education left no room for propaganda, and on the basis of this theologically liberal distinction, the Bureau of Internal Revenue in 1919 interpreted “educational purposes” as excluding propaganda.

Thus, 1919 was the first year in which restrictions on free speech appeared in the tax law relating to philanthropic institutions. From there we see that a guy like Paulo Freire, who was financed by the U.S. government, just gives a Marxist guise to a theological variety of Protestantism that was new in the 19th century.

And how can the ascendancy of theological liberalism be explained? Through the rise of Unitarians to positions of power, as well as the spread of their liberalism through other religious currents. The key year was 1805, just 29 years after independence:

A notable milestone in the progress of liberal theology was the election of Unitarians to leading positions at Harvard beginning in 1805. Another was the triumph of Unitarians during the ensuing decades in taking over Congregationalist churches in Massachusetts. These, however, were only the most visible successes. Although initially associated with Unitarianism, Universalism, and Deism, theological liberalism was becoming an increasingly popular attitude in almost all Protestant denominations, not to mention Judaism. As a result, almost all Protestant affiliations in the United States — even the Presbyterians—were divided over liberal theology, and this division within denominations was often more significant than the boundaries between denominations. To be sure, interdenominational splits still predominated at the surface of American religion, but not far below, there was a growing liberal attack on “orthodoxy”—an assault that was transforming American religion.

Theological liberalism, therefore, had both top-down influence, as it conquered Harvard, as well as grassroots influence, as it actually reached the churches. This explains how it was possible to gain so much social and institutional penetration. Not least, one thing not mentioned there is that John D. Rockefeller Jr. was an adherent of the liberal theology who sponsored its proliferation.

What about liberal Judaism? Anyone who wants to see what it is like can consult the website www.liberaljudaism.org. They promise conversion within 18 months and do not require circumcision! Circumcising yourself, according to the website, “is your personal choice. Reasons for not being circumcised include […] an intellectual reason against the procedure.”

However, the main asset of theological liberalism is that it does not see itself as religious. Unitarians didn’t even see themselves as a religion!

Even when organized into religious groups, such as the Unitarians, theological liberals thought that they formed their beliefs as individuals rather than as members of their groups. The Reverend Aaron Bancroft [1755 – 1839], president of the Unitarian Association and father of the historian, argued that Unitarians were not really a sect but rather were merely a collection of independent-minded individuals. Their “faith was the separate conclusion and result of the action of independent minds, each thinking, inquiring, and deciding for itself, and adopting that belief, for which it was willing to be responsible by itself.”

Now, as the U.S. constitution is liberal and does not admit privileging a single religion, nor mixing it with the State, a religion that does not see itself as a religion is capable of becoming a State religion. It only needs to have followers in strategic positions. They will consider that it is as legitimate to support science in a secular State as it is to support their religious morals.

Evidently, Unitarians were a religion and they had an explicit orthodoxy: every believer must reach the same conclusions alone, without direction from authority. It is a religion that only works with very high self-esteem, since the rest of humanity does not belong to it only because they did not dare to think for themselves. The world is divided between the well-thinking and the mental slaves, whose archetype is the Catholic. This is also a deeply moralistic way of looking at the world: those who don’t think like me are lost; those who think like me are saved and we go to heaven.

What is the obstacle between heaven and hell? In principle, education. Catholics were born into servitude and are slaves to the Pope; but if we free them, they will be able to use their intellect and come to the same conclusions as me and my associates. Yet the fetters were fastened during earliest education; so, there is a need for a non-oppressive education that allows students to think for themselves and reach the same conclusion as mine. No one is ever free and good, except if they think the same as me. And there we see the root of neoconservatism, which wants to drop some bombs to free some people, forcing them to become democratic just because.

Basically, it is a pure supernatural faith: there was no concrete reason for anyone to believe that all the peoples of the world would want to live in liberal democracies, so that the world had reached the End of History with the collapse of the Soviet Union. It was nothing more than a slightly less aggressive and particularistic variant of the Ku Klux Klan dream.