In Mill’s philosophy, the home is turned into a field of the war of all against all, in which the children themselves constitute a threat.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

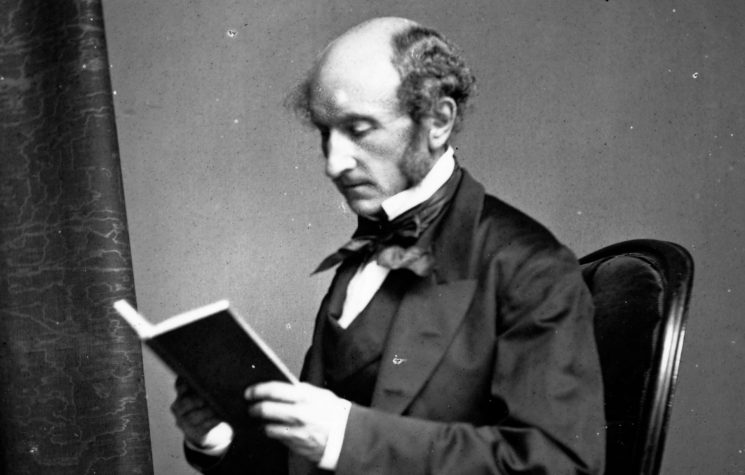

As we have seen in the last text, in On Liberty, the liberal philosopher Stuart Mill argues for the state control over procreation, which would be made both for sparing poor people from existence (making their procreation a crime) and for raising the wages of working class (scarcity of workers would make their salary bigger). Actually, things are not that simple: feeding the offspring is a powerful reason for demanding a wage increase, and it is possible that an employer wants to pay a misery salary just for a greater profit. The lack of a negotiation margin exposes Mill’s liberalism technocratic vein, at least in this phase of his life. (Later he would turn into a socialist; however, On Liberty is surely his most influential work.)

We have also seen that the demand law indeed worked, but to lower wages down by adding women into the labor market. And then we got the worst scenario: two salaries are needed to sustain a home with few children, of whom the woman cannot care as much as she would like.

But Malthusianism seems to be, in itself, a principle of Mill’s thought – for he was the promoter of now-day’s war of all against all inside families.

Let us see: Mill is, like Humboldt, an enthusiast of marriage as an expression of a changing affection, which can be undone at any moment. “Baron Wilhelm von Humboldt” writes Mill in Chapter 5, “states it as his conviction, that engagements which involve personal relations or services, should never be legally binding beyond a limited duration of time; and that the most important of these engagements, marriage, having the peculiarity that its objects are frustrated unless the feelings of both the parties are in harmony with it, should require nothing more than the declared will of either party to dissolve it.”

Mill admits that marriage, which he understands as a “relation between two contracting parties”, creates “obligations […] on the part of both the contracting parties”. Such a contractual relation “has been followed by consequences to others, if it […] has even called third parties into existence” – that is, the children. Therefore, only through procreation, “obligations arise on the part of both the contracting parties towards those third persons”. This book was published in 1859. England has just passed, in 1857, the Matrimonial Causes Act, which makes marriage into a civil contract, instead of a religious sacrament. At that time, equality of men and women at the labor market was an utopia. Even though, Mill thought that a man only had inherent obligations towards the woman he married in the church if there were children – if not, a man could leave her to her own fate.

Let us see now the children. In the last text, we have seen that Mill wanted to criminalize the procreation of those who cannot afford good conditions to their children – but we have not seen which are such conditions. The case of divorce bears nothing exceptional: parents just must have certain spending, regardless their marital status. We can’t know, though, how Mill could expect to ascertain paternity before DNA tests, and we can infer that, no matter how much he cared about his wife and step-daughter, he didn’t care for vulnerabilities of women in general.

Mill specifies the needs of children: food and, what was a novelty, education. This is what he writes in the final chapter of On Liberty: “ Is it not almost a self-evident axiom, that the State should require and compel the education, up to a certain standard, of every human being who is born its citizen? Yet who is there that is not afraid to recognise and assert this truth? […] Instead of his being required to make any exertion or sacrifice for securing education to the child, it is left to [the father’s] choice to accept it or not when it is provided gratis! It still remains unrecognised, that to bring a child into existence without a fair prospect of being able, not only to provide food for its body, but instruction and training for its mind, is a moral crime, both against the unfortunate offspring and against society; and that if the parent does not fulfil this obligation, the State ought to see it fulfilled, at the charge, as far as possible, of the parent.”

Is Mill, then a defender of universal basic education? Not at all. Such a defense would imply the creation of an impartial curriculum, something really hard to do when there are several different religions and competing theories. Therefore, in the sake of liberty, the state will do good by refraining from teaching. But the real motivation is economical: “If the government would make up its mind to require for every child a good education, it might save itself the trouble of providing one. It might leave to parents to obtain the education where and how they pleased, and content itself with helping to pay the school fees of the poorer classes of children, and defraying the entire school expenses of those who have no one else to pay for them.” Educational costs per child are imposed on the middle class, and a paltry education is offered to the poor. It is very different from the old public schools desired by every parent, which used to result in social ascension for the diligent and studious children among the poor.

The Millian state would show up just for making public examinations in order to find out if the children learned whatever they must learn – an to take poor parents into a slave labor camp: “If a child proves unable, the father, unless he has some sufficient ground of excuse, might be subjected to a moderate fine, to be worked out, if necessary, by his labour, and the child might be put to school at his expense.” Isn’t that astonishing? Mill can transform the right to education into a pretext for creating a tax on children and enslaving the poor. Having a child, then, is assuming the risk of ending up in slave labor camp.

All this discussion on family begun with the discussion of the state’s proper role, which should include intervention on the home because of the “almost despotic power of husbands over wives”, who “should receive the protection of law”. Mill therefore takes the state out of public sphere an transfers it into the hell of families, turning wives against husbands, while stimulating men to leave them. The home, then, is turned into a field of the war of all against all, in which the children themselves constitute a threat.