The drama of Russia is that Russia does not understand the West. Thus, there emerges that continual consternation by Russian politicians at the (political) moves of the West at the global scene.

The original article was written by Mr Nebojsa Katic is a Serbian economist and author, who has been living in London, UK since 1992. He holds BSc and MSc in economics and has had a long-lasting career in reputable corporations in the area of finances so far. The original article in Serbian can be read here. Translated, adapted and submitted by Tatiana Obrenovic.

Russia’s problem is not that the West does not understand Russia. The drama of Russia is that Russia does not understand the West. Thus, there emerges that continual consternation by Russian politicians at the (political) moves of the West at the global scene.

Russia is one great European nation whose elite fails to understand its position on the global scene and define itself in it in a rational and unique way. The inferiority complex, immaturity, naivety, conformism and even egoism are the permanent features of a substantial part of the Russian elite. It is to do with that part of it, which seems to be refusing to grow up and cannot grasp the roots and depths of Russophobia in the West. That is the world which is hovering in the triangle of political infantility, naive, pro-Western romanticism and provincialism. (Provincialism here is chiefly the consequence of a long, self-imposed isolation of the USSR from the Western world, the negative consequences of which can be felt even today).

The Slavophile part of the Russian elite has long analysed, at least since the middle of the 19th century, the Russophobia phenomenon and explained it during polemics with the pro-Western part of the Russian intelligentsia. Russophobia is not the product of Russian paranoia and those Western authors who look at Russia if not with benevolence, then certainly with understanding. Russian “independent” media workers who left Russia, now roaming around Europe looking for sponsors, can clearly see that today as well. Bit by bit, these “good Russians” in exile, are able to sense Russophobia “on their own skin.”

Kafkaesque surprise

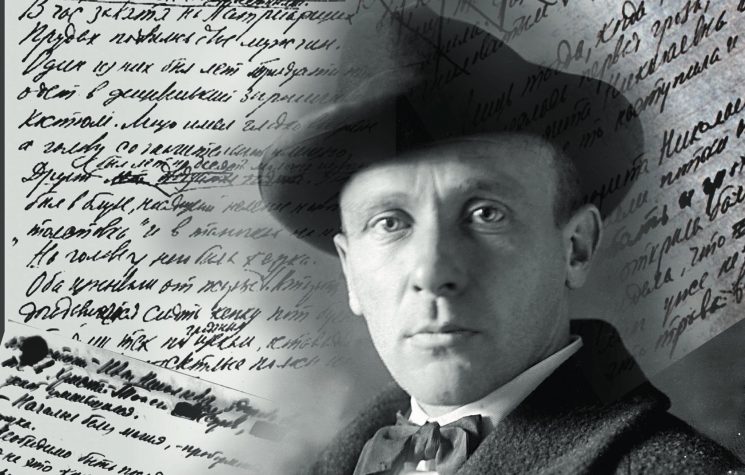

I got an immediate reason for the retrospective to follow, while reading the text by an unknown Russian author, Viktor Yerofeyev, which was published in Politika in their cultural section, syndicated from the German newspaper Zeit (24 December 2022). In his article, Yerofeyev communicates to the public with lots of resignation what woes he is going through in Germany. The text is not inspiring due to its quality, but quite the opposite — due to its banality and absolute political puerility.

The reader following what is happening in the Western media scene may well expect that Yerofeyev, appalled at the Russophobia propaganda unheard of since the Second World War, warns of the dangerous consequences of fuelling such atavistic hatred. No. Yerofeyev in his long text writes about the troubles he is going through in his pursuit to open up a bank account with the German bank and get a credit card. Accordingly, there is an ambitious title in the text “Kafkaesque absurdity in die Deutsche bank.”

A month after the beginning of the war in Ukraine, Yerofeyev left Russia with his family and as it is written, he left “the atmosphere of lies and repression” and he fled to the “free” Germany in which there are no lies and repression, surely. Yerofeyev got a job as a visiting professor of literature in Lüneburg. He was welcomed “cordially” and Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung provided him with comfortable accommodation.

In brief, everything began the way that could not possibly be better, when all of a sudden…. Imagine that, you are living in Heinrich Böll’s House, you are rounding up your new novel, you are participating in radio and TV broadcasts in prestigious German media and all of a sudden, out of the blue, you end up in a Kafkaesque novel and you become his “anti-hero”.

After this idyllic beginning, there follow the author’s banking woes. (Russian citizens are under financial sanctions in the EU, so not even Yerofeyev was able to circumvent that).

Yerofeyev is moved with the attention he was welcomed with: “I learnt to appreciate high humanistic culture in Germany a long time ago and now I have familiarized myself with their hospitable frugality which, certainly, pleasantly delighted my wife and children.” His four year-old daughter was pleasantly surprised as well, that is what happens with the children of that age. This is where the author, overwhelmed with gratitude, began expressing his strong views more freely so as to, most probably, touch sentimental German audience, sympathetic towards children.

The person who reads Yerofeyev will be under an impression that bankers’ Russophobia is most probably the only form of Russophobia which exists in the West today. Such is the author’s bitterness that he compares the bankers’ treatment of the Russians with the treatment of another nation, much earlier, under the Nazis. In case the Russians were able to open bank accounts in the Western banks with no difficulty at all, everything would have been all right and this only Russophobia phenomenon would vanish into thin air.

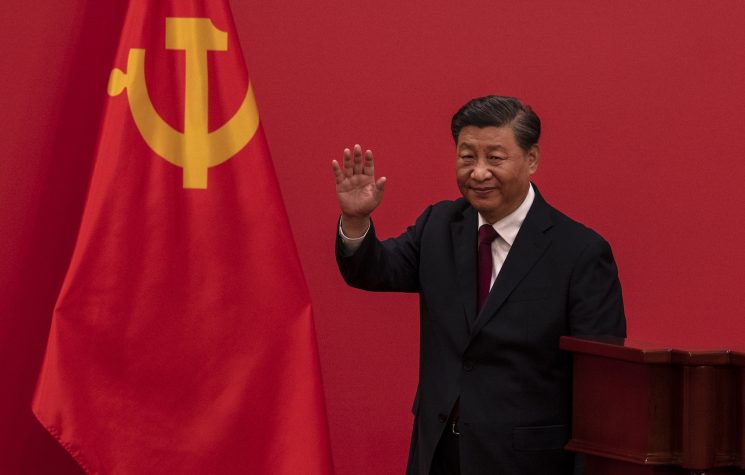

In his media appearances Yerofeyev, as is appropriate for an enlightened Russian liberal, is fiercely against the Russian politics and staunchly agrees with the Western view of the war in Ukraine, and particularly with Putin’s role in it. In one newspaper interview, Yerofeyev gave his intellectually elevated psychoanalytical diagnosis of the causes of war. According to him, the war started because Putin felt bored, and Yerofeyev came to that conclusion by analysing photos of the Russian President. (Come to think of it, this is most probably the only war which began because of the sheer boredom of one man, i.e. if we took Yerofeyev’s words seriously).

Yerofeyev’s banal text is a mere caricature of some more dangerous phenomena which have for centuries haunted the Russian elite, and which is the basis of its servile attitude towards the West. And many more serious representatives of the Russian thought encounter hardships and dilemmas than merely the immature Yerofeyev.

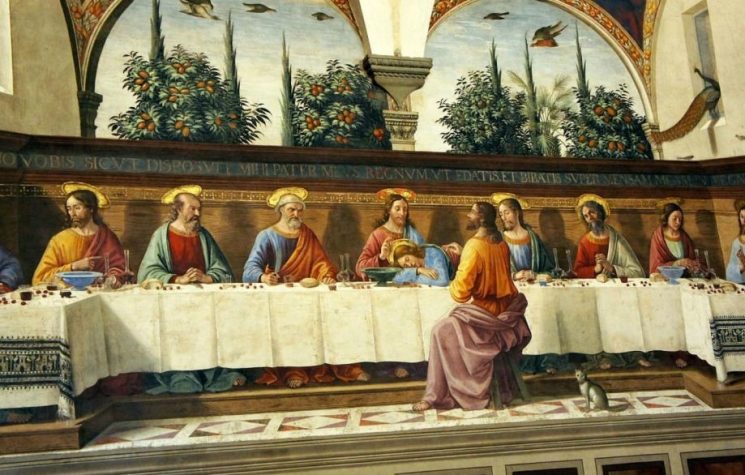

Dostoyevsky and Europe

“Oh, the European nations are unaware of how much we love them! I believe the generations to come after us will understand that to be a true Russian means to strive for all the European contradictions to be reconciled for ever, our Russian soul will be the way out from the European misery, ours is the soul omnihuman and all-uniting, and it will embrace all our brothers with love, and it will, perhaps, utter even the last word of general harmony, brotherly unity of all nations according to the law of Christ’s evangelical learning! If Pushkin had lived longer, he would have, perhaps, created great and immortal Russian characters, who would have been more intelligible to our European brothers, which would bring our brothers much closer than it is the case now; we might succeed in explaining all the truth of our pursuits to them, and that is how they would understand us better than they understand us now — they would stop looking at us, them being all so arrogant and with distrust the way they are doing now’.

The Writer’s Diary 1877-1881

The quote above is part of the famous speech Dostoyevsky gave in June 1880, on the occasion of the unveiling of the monument dedicated to Pushkin in Moscow. Seven months later Dostoyevsky died.

In these humanistic words filled with Christian sentiments, for which even Dostoyevsky says that they may have sounded “emotional, overexaggerated and unreal”, there is the tragic delusion, which generations of the Russian intelligentsia used to live with. In the very core of this delusion lies the belief that misunderstandings with Europe come from the fact that the Europeans understand neither Russia nor the Russians. And if Europe understood Russia, in that case it would…

The reader might think that Dostoyevsky lost his way and got into my text by mistake, and that it would be much better if I chose a pro-Western Turgenev as an example. Those who are greater connoisseurs of Dostoyevsky’s work would remember that he was not a naive idealist in his political texts and he did not fall prey to delusions. His understanding of Russia and the Russian nature, his understanding of political processes in Europe as well as his lucid predictions oft were prophetically true. In his views, there is not much difference between him and the Russian realists thinkers, such as the Slavophile Nikolay Danilevsky and the Orthodox “universalist” Konstantin Leontyev, for instance.

By the way, Leontyev, who held Dostoyevsky in high esteem, criticized this part of the speech in his essay “On world love”.

“And then, suddenly, that speech! Again those ‘nations of Europe’! Again that ‘last word of the general reconciliation’ — Et, tu, Brute! Alas, you too!…”

In January 2014. I posted the excerpts from the famous Writer’s Diary by Dostoyevsky on my blog. His lucid and perceptive insights made me name this addition: “The 21st century through the eyes of Dostoyevsky”. In the part which refers to Europe, Dostoyevsky writes (chronologically after the said speech):

“Europe is ready to praise us, to pat us on our head but they will not accept us as their own, they will despise us both secretly and openly, they will regard us as the people of a lesser order, we are repulsive to them, yes we are repulsive to Europe, particularly when we hang around ‘her’ (Europe’s) neck and when we kiss her in a brotherly manner.”

Writer’s Diary 1877-1881

And one more earlier prophetic observation:

“if it so happened that Russia decides not to disrupt anything, but to simply take care of its own interests, all the other balances would instantly unite into one and they would advance against Russia. So, you see, you are disrupting the balance, they would tell.”

Writer’s Diary 1876

How shall we reconcile the quoted parts from Dostoyevsky’s speech and his numerous observations which are in absolute opposition to this speech? I believe that it is to do with a desperate hope, it is to do with the conflict of reason and heart, where the heart cannot accept the existence of irrational, instinctive, almost eternal hatred which no evangelical love can overpower. If such an observation sounds too harsh, let us ask ourselves if among the great European writers there is anybody who expressed similar utterances and called for evangelical or any other love towards Russia.

If the lyrical episode from the speech dedicated to Pushkin came to be from a better part of Dostoyevsky’s soul, aggressive political views of Solzhenitsyn, which he presented for decades in the West during his exile, came from the darker part of his soul. In his speeches and political texts, Solzhenitsyn showed gross misunderstanding for the Western world, its goals and its political processes, which happened on the global scene, and before his eyes wide shut.

Solzhenitsyn and provincialism

Alexander Solzhenitsyn spent 20 years in exile as an apatride — from February 13, 1974 to May 27, 1994, when he returned to Russia. During his exile he lived in Germany and Switzerland for a while, only to move to the USA in 1976, to Vermont, where he remained until he returned to his homeland. For the sake of curiosity, when he was exiled from Russia, he found himself in the house of Heinrich Böll mentioned by Yerofeyev.

Unlike the modern-day Russian emigrants, Solzhenitsyn was not subservient towards his hosts and he did not restrain himself from severe criticism of different aspects of the Western life. Solzhenitsyn criticized the Western consumerism, the lack of spirituality, shortage of citizens’ bravery, the democratic mechanisms which are the barrier to governing, surplus of rights and shortage of obligations for the citizens of the West, etc. This sort of conservative criticism exposed him to assaults from different sides of the Western political spectrum. (Solzhenitsyn’s views were scattered all over in his speeches and his own texts. The most famous are his Harvard Address from 1978. “A World Split Apart” and the text from Foreign Affairs from 1980, “Misconceptions About Russia Are a Threat to America”).

Anybody who suffered terribly under Communism only because they said or wrote something which those in power did not like, had the right to any kind of anger, and even hatred for the government. The trouble with Solzhenitsyn was that his anti-Communism and hatred for the USSR (not against Russia) deranged his sanity. If there was any lucidity in his criticism of the West, his geopolitical analyses and talks were borderline disorder, and at times these were foolish.

One of such foolish claims was related to the Second World War. According to Solzhenitsyn, the USA should not have helped and reinforced Stalin through lend-lease programme and enabled him to win the war. Democratic countries should have defeated Hitler by themselves because they were strong enough.

When we talk about the post-war world, according to the views of the author, on one side of the geopolitical divide is the powerless and indecisive West, and on the other there is the aggressive, expansionist USSR. The naive West is unable to see that the prophet, the new Jeremiah, has come to warn them. Solzhenitsyn’s Jeremiah “epic cantos” and his shrieks of this sort were repetitive.

According to such understanding of geopolitics is his criticism of the detente from the 1970s. Calls for the reckoning with the USSR often sounded like a call for a new world war. He was trying to convince the world public that the coexistence with Communism is impossible and that the USSR wanted to rule the world by way of military conquests, terrorism and through subtle subversion of societies from within. Western Europe was in immediate danger of being subjugated, and Western politicians were naive to believe that the USSR wanted peaceful coexistence. In line with Solzhenitsyn’s thoughts, “Eastern politics” of Willy Brandt was suicidal for Germany; American departure from Vietnam was a huge mistake, as well as the mistake of tolerating Cuba and its activities in Africa.

Solzhenitsyn was a great follower of the work of John Paul II whom he met in 1993. The author considered the election of this Pope a divine gift and he supported not only Pope’s attacks on Communism in Europe, but also his harsh attitude to the Catholic churches in Latin America and theology of liberation they advocated for.

Unlike the Russian infantile liberals, unlike the Russian Orthodox Christian romantics, Solzhenitsyn was dominated by political provincialism. He did not succeed in understanding the Western world and its goals, although he spent twenty years in its epicentre. Only after his return to Russia and in the midst of its ruins did Solzhenitsyn begin thinking more clearly, but not enough and only too late. His fame of a dissident faded away, and he stopped being relevant not only in the West but in Russia as well. (Yerofeyev, for instance, dismissed Solzhenitsyn as a provincial teacher and a bad writer).

Schmitt’s lesson

If there were enough sensible people in Russia, school curricula would introduce Carl Schmitt as a mandatory reading list with his famous essay The Concept of the Political.

It would be well worth it if the school students learn its most important parts by heart, and all those who want to join the civil service should take an exam “in Carl Schmitt”.

The Russians would learn in this way that the whole political sphere is reduced, as I wrote at the time, only to one thing: to the clear distinction between friends and foes, in which the decisive political moment is exactly that one in which the foe is recognized as an enemy with crystal clarity. In Schmitt’s universe, the enemy of a country is the one who denies its way of living or it is its threat, anybody who is in existential terms different, the one who is a foreigner, the one who is “the other.”

It is insane to believe, Schmitt says, that naive and powerless nations, given that they do not endanger anybody, can have friends only, or that the enemy will be moved by their weakness and inability to defend themselves. In the field of cruel realpolitik, nations who believe in such fairy tales are destined to disappear.

The enemy does not come only from outside. They can exist from within the country/state and they can place it in danger. Schmitt does not hide his (Hegelian) view that the state must stand above society and that that is the only way to surpass, neutralize and harmonize individual and group interests. Under the influence of his Weimar Republic experience, Schmitt considers that anybody who challenges the survival of a state must be neutralized and they cannot hide behind the right given by the Constitution or the laws. In extreme, critical situations, legal norms cease to be valid and they give way to the political decision.

Schmitt severely criticizes the political abuse of the terms “universalism”, “humanism”, “altruism”. Universalism and humanism in the political sphere represent an ideological instrument of imperialism, above all of economic expansion, and the terms such as “pacifism” serve the purpose to deceive only. In that hypocritical context, the war is declared as unacceptable Evil. On the other hand, sanctions, interventions and penalizing expeditions, violent pacification and similar brutal political and military means become quite acceptable — in the name of humanism, surely.

By reference to universalism and humanism, the enemy as a category ceases to exist. The term “enemy” is therefore being replaced by the term “destructive factor” and in this way the opponent gets to be dehumanized and deprived of their dignity and legitimacy. They “disturb and endanger” the global peace and universal values, and thus they are out of the framework of humanity and laws. In this way it goes without saying that it is justifiable to undermine states/countries in the name of universal principles of humanism, and without formal declaration of war. Critically anticipating the time which comes, Schmitt says that the wars waged for the sake of preserving and increasing economic power aided by propaganda will turn into a crusade and the war in the name of humanism.

And exactly on the concept of the political, exactly in the way Schmitt defines it, the West is functioning with great success, having used that humanistic rhetoric which Schmitt despises. By recognizing and naming their enemy in a crystal-clear way, the West is waging decisive, persistent and uncompromising politics with all available means.

Understanding Russia

Longstanding, incessant Russophobia does not come from not understanding Russia. It cannot be explained not even because of the fear of Russia nor as a consequence of conflicting, rational geopolitical interests the way it was in the 19th or the 20th century. If that were so, Russophobia would have disappeared (or at least weakened) over the past thirty years in which Russia became tragically powerless and lost its Empire. It (inadvertently) allowed NATO to come to their doorstep and to expand to Ukraine the following day, and then the day after the following day, once some coloured revolution might oust President Lukashenko, most probably to Belarus too.

The problem of Russia is not that the West does not understand Russia. The drama of Russia is that it does not understand the West. Thus, that continual consternation of the Russian politicians at the moves by the West on the global scene — the consternation which lasts for decades. If Russia had recognized with crystal clarity who its enemy was/is, if it managed its politics in line with that recognition, the USSR disintegration may not have happened or that disintegration may have had different contours. In that case, there would not have been the fratricide war in Ukraine, and neither would NATO have opted for a new, great Drive to the East. Russian weakness thus became the key factor of global instability not only in Europe; which brings us to the beginning of the text, to the inability of the Russian elite to reach an agreement on national goals, interests and means by which to achieve these goals. It can soon turn out that the current unity on the issue of war in Russia is short-lived.