Islam is not, as the collective West would have us believe, some huge, menacing medieval fortress. No, Islam is a slender and elegant palace.

The Ministers of Foreign Affairs of Iran and Saudi Arabia, Hossein Amir Abdollahian and Prince Faisal bin Farhan al Saud signed one of the most significant joint statements in Beijing at the beginning of April this year, which concerns not only the relations between these two nations, but also the future of countries which have long wished for peace and stability and which, all together, today we often define as the Greater Middle East — a vast area that includes North Africa, parts of East Africa, the Middle East in the traditional interpretation of the term and Central Asia; a space that stretches from the Atlantic in the West to the borders of Russia, China, and India, and in such a way that it unites all predominantly Muslim countries except Indonesia.

The complexity of the relationship between Saudi Arabia and Iran is marked by decades of religious, political, economic, and even military rivalry, which over time grew into a very dangerous proxy conflict that was played out by the more or less open and multi-layered support that these two important and powerful Middle Eastern nations provided to the opposing factions in Syria, Yemen, and Iraq, but also through their involvement in complex and very sensitive religious and political relations in Lebanon, Bahrain, and Qatar. That this proxy conflict began to take on global proportions became evident from the fact that it had a very unfavorable impact on the stability of the broader Eurasian and African geopolitical spaces. On several occasions, the Iranian-Saudi proxy conflict threatened to develop into an open and full military confrontation, primarily because Israel and the Western powers led by the U.S., perfidiously, but let’s be honest, at the same time, very skillfully, with diplomatic intrigues and deceptions, by using their intelligence channels and proxy armies on the ground, as well as other means of hybrid war, helped to deepen and intensify this conflict as much as possible. It is safe to say that the U.S. and its allies have been waging a hybrid war for decades, not only against Iran but also against Saudi Arabia. The only difference is in the intensity, transparency of the methodology, and obviousness of the goals of that hybrid war. As for Iran, the goal has been to destroy it at all costs and dismember it as a state through a combination of economic sanctions, proxy wars, color revolutions, and various other means of hybrid war, including the possibility of direct military interventions, while against Saudi Arabia, a silent and insidious economic and cultural war has been waged.

If the relations between Iran and Saudi Arabia were strained and sensitive before, they were brought to a boil when the Saudi authorities executed the influential Shia cleric Ayatollah Sheikh Nimr Baqir al-Nimr on January 2, 2016, who although a citizen of Saudi Arabia, enjoyed a huge reputation even outside the borders of his homeland, primarily in Iran, Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon. Two years earlier, he was sentenced to death on very serious charges, probably the most serious of which was that during his arrest in July 2012, he resisted with a firearm by shooting members of the security forces who were arresting him. Sheikh Nimr al-Nimr was also accused of a range of other offenses, such as disrespecting the ruler, attempting to allow foreign powers to interfere in Saudi internal affairs, provoking “sectarian” hatred, and inciting demonstrations against Saudi authorities. Sheikh is accused of even directly participating in the protests in Saudi Arabia in 2011 and 2012, which were part of the violent and bloody momentum of the now infamous “Arab Spring”. Dealing with the guilt or innocence of Sheikh Nimr al-Nimr at this historical moment, in the name of reconciliation and peace, is probably something that is far more advisable to leave to the historians of the future, because tragic history is impossible to change, while with the power of goodwill and wisdom, it is possible to build a better future, and no opportunity to do so must be missed. In this particular case, history testifies that numerous human rights organizations, even Western ones, protested in vain against the death sentence handed down to Sheikh Nimr al-Nimr, while Iran went a step further, threatening Saudi Arabia with serious consequences if it did not abandon its intention. Just one day after that execution, which Saudi Arabia, unfortunately, did not give up, in the early hours of the morning, Iranian protesters, enraged by the tragic death of their favorite cleric, forcibly entered the Saudi Arabian embassy in Tehran. After that incident, Saudi Arabia rushed to cut off all diplomatic relations with Iran, joined by its closest allies Bahrain, Sudan, and Kuwait, while the United Arab Emirates downgraded diplomatic relations with Iran.

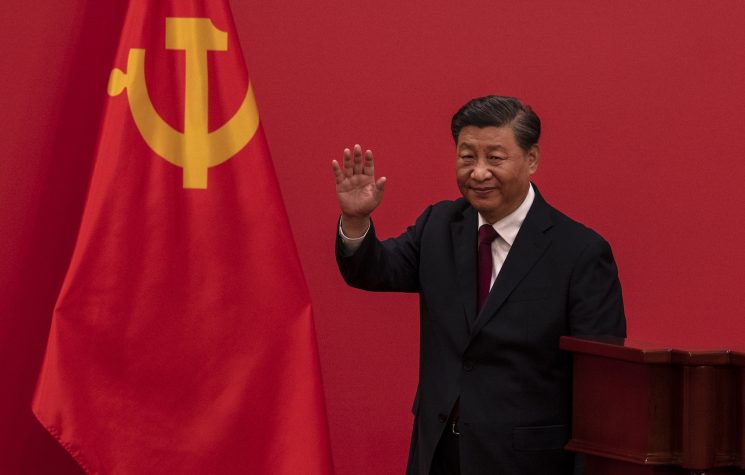

Only when the tragedy of all these and many other previous events, as well as the entire painful and long history of unnecessarily strained and often hostile relations between Iran and Saudi Arabia, is fully understood can the full significance of the joint statement signed on April 6 of this year by the two countries in Beijing, with the mediation of China and under its patronage, be recognized. Saudi Arabia and Iran announced the full restoration of diplomatic relations, the reopening of embassies and consulates, and agreed on mutual visits by the highest representatives of the two countries. This seemingly small and symbolic step is in fact a major and decisive historical turning point that will completely and permanently change the geopolitical landscape of the Greater Middle East, tearing it from the clutches of the destructive influences of Israel, the U.S., and the rest of the collective West and placing it comfortably in a new and growing community of equal nations of Eurasia and Africa. It is a coalition to which Saudi Arabia and Iran most certainly belong — an alliance of nations that have found enough courage, strength, and prudence to stand up to Western hegemony, imperialism, and neo-colonialism once and for all and set off for full freedom.

Even in the midst of their misunderstandings and conflicts, Saudi Arabia and Iran were aware of the absolute necessity of their good relations. At the beginning of March, now long ago in 2007, the late King of Saudi Arabia, Abdullah bin Abdulaziz Al Saud, and the then Iranian President, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, held a very promising summit whose probably greatest contribution was that both sides agreed that there was a conspiracy by common enemies to sow the seeds of evil and discord between Sunni and Shia Muslims. Unfortunately, this mutual understanding of the great danger that threatens both nations, from the domain of theory and empirical and logical reasoning, failed to develop into some concrete steps in foreign policy practice. Just a few years later, this enabled the collective West, primarily the USA and its most important Middle Eastern ally Israel, to ignite the hellfires of the “Arab Spring” by mass manipulating the population of the Greater Middle East, primarily through the Internet, social networks, and the media. The most tragic legacy of that wave of unrest, violence, and lawlessness is the bloody civil wars that have left the deepest scars in Syria, Yemen, Iraq, and Libya. American perfidy in relation to any initiative that would lead to full reconciliation between Iran and Saudi Arabia illustrated itself very well in November 2010, when WikiLeaks published several supposedly confidential documents, from which, in very graphic language, supposedly in the words of the late King Abdullah, Iran was called “a snake whose head must be cut off without hesitation” and an immediate U.S. attack on Iran was demanded. Since all this was happening at the very moment when the great hunt of the Western intelligence services for the founder of WikiLeaks, Julian Assange, was launched, Iranian President Ahmadinejad, most likely based on the knowledge of the Iranian intelligence services, decisively rejected the authenticity of those documents, which were undoubtedly very maliciously planted — a practice of the American intelligence services that we could reasonably assume is something that happens relatively often, even these days.

After the interruption of Saudi-Iranian diplomatic relations at the beginning of January 2016, there were several attempts by Pakistani and Iraqi politicians to bring the two sides to the negotiating table and settle the conflict, but we should not be surprised that it was China that managed to finally implement that initiative to the end. Namely, China and Russia, which have previously also tried to mediate between Iran and Saudi Arabia on several occasions, are the two Eurasian nuclear superpowers whose political leaders, together with their counterparts from Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan, founded the Shanghai Cooperation Organization on June 15, 2001. The goal of the SCO is to promote friendship and alliance among its members in order to improve their political, security, economic, military, scientific, and cultural cooperation. One of the very important goals of the organization is the fight against terrorism, extremism, and separatism. It is not surprising that interest in membership in this Eurasian organization quickly grew. Two populous Asian states, India and Pakistan, both nuclear powers themselves, joined the SCO in 2017, and a large number of Asian countries have shown interest in gaining observer status as soon as possible. What is most important in this story is that on September 17 of last year, Iran signed the accession memorandum, which was ratified by the Iranian parliament on November 27. This means that during this year, most likely before the SCO Heads of State Summit to be held in New Delhi at the end of June this year, Iran will become a full member of this organization. Meanwhile, after the meeting of the government of Saudi Arabia chaired by King Salman and the decision that was made at the time, this kingdom was at the end of March this year among a large group of Asian countries that acquired the official status of partners in the dialogue with the SCO, which is the beginning of the process that leads to full membership. The official procedure that gave Saudi Arabia its current status in the organization began much earlier, at the SCO Summit in Dushanbe, Tajikistan, in September 2021. There is no doubt that the processes of joining Iran and Saudi Arabia to the SCO and the process of reconciliation between the two Middle Eastern regional powers that started last year with the mediation of Chinese President Xi Jinping are closely connected and inseparable. Membership in the SCO is a great opportunity for the economic and every other prosperity of Iran and Saudi Arabia, but it makes sense and is possible only under the condition of complete reconciliation of the two states, which is again a benefit for both sides by itself. To the satisfaction of many, the two once-conflicting nations not only renewed their bilateral relations but improved them in a very short period of time. Contrary to all predictions and wishes of Western politicians and analysts, Saudi Arabia and Iran are currently on the way to becoming allies through their membership in the SCO. Iran-Saudi détente is already becoming Iran-Saudi entente! This not only paves the way for permanent peace in Yemen and Syria and the healing of numerous other painful wounds in the region, but it is most certainly a hint of much larger and more positive geopolitical changes in the Greater Middle East, after which the biggest losers will be the USA and its vassal out of interest, Israel, while the negative consequences will definitely be strongly felt by the UK and the EU countries. However, in no case should we rejoice too soon. Although the foundations of Eurasian-African integrations are already largely laid and are undoubtedly strong and stable, and although these processes of the association are accelerating with geometric progression, the alliance of equal nations has not yet reached the level of full functionality. This gives another great opportunity for the U.S. and its vassals to use reliable methods in order to sabotage the great Eurasian-African merger and replace it with a new series of tensions, conflicts, and civil and interstate wars. Only under such conditions could the U.S. once again dominate the Greater Middle East.

One of the basic and proven mechanisms that the U.S. and its allies will undoubtedly try to use in their supposed new campaign in the Greater Middle East is the incitement of sectarian hatred and bloody conflicts among Muslims. Unfortunately, that well-established strategy of the American hybrid war against the Islamic world has so far produced results that Washington could often be quite satisfied with. Regardless of the fact that the Americans have experienced failure in Syria, the paradigm of that essentially primitive strategy is most obvious precisely in the example of the civil war in that now-suffering but once rich and happy country. In the first phase of the hellish project, the U.S. would always generate the necessary level of irreconcilable discord through diplomatic and intelligence intrigues, false promises, and bribery of opposition, religious, and other leaders, and consequently, the conflict would soon turn into a full armed conflict and great bloodshed. In the next step, the U.S. would provide political, logistical, financial, and military support and assistance to a certain number of warring factions. On the other hand, harsh economic sanctions and international isolation would usually be imposed on the legal representatives of the hitherto prosperous Muslim nation, which was to be destroyed and subjugated. In the last phase, if it was really necessary, the U.S. would launch its own military intervention, especially from a safe height and distance, so that by supporting one of the parties to the conflict, the set goals would be fully achieved. At the end of the bloody saga, the goal is for Anglo-Saxons, Zionists, and their European minions to exult and rub their hands in satisfaction. This form of hybrid warfare, in which two or more belligerents exterminate each other in order to achieve U.S. interests with as few American losses in manpower and equipment as possible, has been practiced around the world. Nonetheless, it turned out that for some reason, Muslim nations are particularly vulnerable in relation to this American strategy, and therefore it is necessary to get to the heart of the problem and find the causes of this weakness. Is it possible to “immunize” religious, political, and cultural Islam in relation to all possible vile and vicious forms of the undeclared hybrid war waged against it by the collective West? Finally, who are the potential allies of Muslims in that epic clash of civilizations that is now clear to everyone as inevitable?

Just by asking these two questions, which are imposed by their obviousness, the answers to them are hinted at to some extent. Let’s start with the easier of the two puzzles. Russia is a nation that, like the majority of Muslims, is in a centuries-long and continuous conflict with the West. Although, since the time of Peter the Great, Russia has largely turned towards Europe in a cultural sense and its culture has become not only inseparable but also a huge part of the European cultural heritage, its civilizational conflict with the West has never been overcome; on the contrary, in the time in which we live it is experiencing its climax. The proxy war that the collective West is waging against Russia through Ukraine will only speed up the process of a major redefinition of the Russian nation that began during the time of the Soviet Union, if not much earlier. The great Russian nation outgrew its narrow Slavic and Orthodox Christian frameworks of identity and became a Eurasian nation, in which Islam occupies an increasingly important place. Western and pro-Western analysts note with concern that Islam is becoming “a pillar of Russia against the collective West.” And indeed, Russian Muslims, who today make up 10% of the population of the Russian Federation, proved their loyalty to the motherland and their uncompromising Russian patriotism, which could put many other Russians to shame, by fighting fiercely in Novorossiya and Ukraine against the beast, who crawled out of hell and started its great expansion to the East under the banners of NATO and the Nazi regime from Kiev. Russian Muslims, like few others, recognize in this onslaught of the collective West a kind of renewal of the crusades experienced not only by the Muslims of the Greater Middle East but also by the Russian Orthodox Christians in the 12th and 13th centuries, when they were forced to defend their freedom and bare survival against aggressive and persistent raids of the Teutonic Knights and other European crusaders. Ramzan Akhmadovich Kadyrov, a Russian politician and statesman, President of the Chechen Republic, Hero of the Russian Federation, and Colonel General of the Russian Army, is one of the most respected Russian Muslims and at the same time a man who without hesitation called for the Great Jihad against Nazi Ukraine and Western Shaitans. The prestige and reputation of the Kadyrovtsy, the Chechen fighters led by Kadyrov who fight in Novorossiya and Ukraine, are such that the mere mention of their name causes chills and panic among the ranks of Ukronazis, Western mercenaries, and volunteers. That Russian Muslims are not only fierce fighters of the Russian Army but also a “shining element of the Russian cultural code” was repeatedly stated by Russian President Putin, who recalled at the same time the edict by which Russian Muslims received such spiritual autonomy 235 years ago that they still do not have anywhere in the West today. Back in December 2001, President Putin spoke about how Russia is a unique place in the world, where Orthodox Christianity and Islam have coexisted in harmony and peace for hundreds of years, and last year he emphasized that Islam and Christianity share identical humanist values. During that long span of 22 years, the Russian president has shown consistent benevolence and friendship towards the Muslim world and Islam in general, which have not gone unnoticed. Of all the Muslim countries on the planet, only Albania joined the so-called “international sanctions” imposed on the Russian Federation by the collective West, and this is probably a good measure of the reputation that the Russian president and the nation he leads have in Muslim countries. Therefore, Russia is and will be until the end of time a great and natural ally of Muslims, and there is no doubt that with the further and unstoppable progress of Eurasian-African integrations, it will be to an ever greater extent. Through these same efforts and struggles for a new, multipolar world of equality, Muslims, to the absolute astonishment of the collective West, gained another very powerful ally, namely China. The already mentioned initiative and the mediation of Chinese President Xi Jinping are most certainly only the beginning of a grandiose undertaking of Chinese diplomacy that will establish stability in the Eurasian and African regions and permanently remove the USA and its vassals from the game. The Chinese have wisely realized that American or Western influence in a Eurasian region can only be strong if there is instability in it that tends to chaos, conflicts, and wars. Realizing that the best way to secure its borders from American aggressive expansion in the long term is to establish peace and stability in Eurasia and Africa, China, unexpectedly for many, has become a great firefighter and peacemaker of the East. Russia, due to the bloody war that it is waging against the collective West at the moment, is temporarily unable to join these Chinese efforts more actively, and that is why, just like the Muslim nations, it is grateful to China for acting in the best interest of all the peoples of Eurasia and Africa. With the support of two superpowers, Muslims today are anything but alone and have allies to rely on. All that is required for the ultimate victory over the common enemy is for Muslims to learn to be better friends to themselves.

As for the answer to the question of how to overcome the historically proven political, ideological, and cultural weaknesses that Islam has shown so far in relation to the onslaughts of the West, its extraordinary complexity is obvious even to superficial connoisseurs in this matter. The core of the problem lies in the religious diversity and divisions within Islam, which unfortunately arose very early, at the very beginning of its expansion. Immediately after the death of the Muslim Prophet Muhammad in 632, the Messenger of God, the founder of Islam, and the religious and political leader who united a large part of the Arabian Peninsula with the new religion, a fatal dispute arose over who should be his successor. A section of Muslims supported Abu Bakr Abdullah ibn Uthman Abi Quhafa, who was Muhammad’s close associate and father-in-law. Another large group of Muslims favored Ali ibn Abi Talib, the Prophet’s cousin and son-in-law. This conflict, the essence of which was certainly largely of a purely political nature, led to the tragic religious split of Islam into two large branches, Sunni and Shia, and the consequences of that great historical turning point not only marked the centuries that followed in the areas lived by Muslims, but they are felt very strongly even in modern times, as is very visible in the history of the conflict between Saudi Arabia and Iran, which fortunately finally came to an end. Today, there are over 2 billion Muslims on the planet, and according to some demographic indicators, Islam will become the religion with the most followers in 2050. The Sunnis, who are the descendants of those Muslims who chose to follow Abu Bakr, make up the absolute majority of 85–90%, while the descendants of those who followed Ali are called Shias, and they make up 10–15% of the ummat ali-Islam, or ummah, which is an Arabic word that denotes the community of all Muslims on the planet. However, this calculation is rather rough and is far from describing all the complexity of the situation in the modern Muslim world. First of all, there is a third denomination of Islam, Ibadism, which, although overshadowed by the number of Sunnis and Shiаs, with slightly less than 3 million believers, should not be left out of this story. Secondly, within Sunni and Shia Islam, there are not only different schools of Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh) and theology (aqidah) and their branches, but also movements that represent mysticism or even political and ideological aspirations. Even when these schools and movements belong to the same major branches of Islam, there can be greater or lesser theological and legal disagreements among them, and when it comes to movements, even open intolerance. The four major schools of Islamic jurisprudence in Sunni Islam are Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi’i, and Hanbali, and the theological schools are Athari, Ash’ari, and Maturidi. In Shia Islam, there are three schools of Islamic jurisprudence: Ja’fari, Zaidi, and Isma’ili, the most important of which is the first one, which is associated with Twelver Shi’ism, also known as Imamiyyah, the largest branch of Shia Islam, to which about 85% of the believers of this branch belong. It is also very important to mention the mystical-ascetic movements within Islam, whose numerous orders (tariqahs) are collectively called Sufism. Here, however, we are not talking about any special branches of Islam because these mystical teachings were created and developed both within Sunni and Shia Islam. Regarding Islamic movements, it is necessary to mention two ultra-conservative, mutually very similar, and related movements, Salafism and Wahhabism, which arose within Sunni Islam. Salafism was often mentioned in the world media as an ideology that inspired radical and militant Islamist groups, including in connection with the Islamic State. Finally, there is also the very interesting phenomenon of non-denominational Muslims, where it is either difficult to establish which of the branches or schools of Islam they belong to, or they consciously avoid making a statement about it, identifying themselves simply as Muslims without any further definitions.

Non-denominational Muslims are most numerous in Albania, Kyrgyzstan, Indonesia, Mali, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan, Russia, and Nigeria. Finally, we must mention the existence of Muslims whose ties to Islam are more cultural than religious in nature. “Cultural Muslims” is a term sometimes used for people who identify themselves as Muslims even though they do not practice all or any religious rituals or do not strictly observe all religious obligations and prohibitions. However, this superficial description of the branching of Islam does not bring it close to completion. In fact, the matter concerning the branches, sub-branches, schools, and movements of Islam is so complex and voluminous that its understanding requires enormous mental effort, even for those top secular experts who have narrowly specialized in this field. In the same way, top Muslim theologians and clerics who belong to certain branches and schools of Islam do not have to be good connoisseurs of other branches at the same time and even do not necessarily have a full idea of the complex branching of this great world religion. Unfortunately, this can lead to the creation and nurturing of prejudices, unyielding exclusivity, and even intolerance that can turn into sectarian violence. This is exactly what the Muslim world must overcome in order to continue its development and progress, not only in the spiritual sense but also in the cultural and material ones.

Relations between Sunni and Shia Muslims are most important for the future of Islam, and if they were smoothed over and religious conflicts between them were overcome, it would have a beneficial effect on all other areas of social and cultural life in the Greater Middle East, including its geopolitical stability. The history of the bloody separation of these two great branches of Islam began a little more than two decades after Muhammad’s death and previous disagreements over who should succeed him, as a real civil war broke out among Muslims. That was certainly the last thing the Prophet Muhammad wanted. The Battle of Camel in 656 (also known as the Battle of Jamel) near Basra, Iraq, was the first major and tragic engagement of the First Fitna (First Islamic Civil War, 656–661), in which Muhammad’s closest relatives and friends clashed. On one side was Muhammad’s cousin and son-in-law Ali, and on the other were the Prophet’s widow Aisha, his close friend Talha ibn Ubayd Allah al-Taymi, and the faithful commander Zubayr ibn al-Awwam. A year later, Ali, who emerged victorious from the first battle, clashed with the rebel governor of Syria, Mu’awiya ibn Abi Sufyan, in a particularly bloody battle, the Battle of Siffin, which ended without a winner but with heavy casualties — over three days, around 70,000 fighters were killed in action. Ali, whom the Shias consider their first Imam, that is, the first legitimate successor of the Prophet Muhammad, and the Sunnis deeply respect as one of the Prophet’s ten closest friends who earned a place in paradise during his lifetime, died in 661 as a result of being wounded in an assassination attempt that was organized by a third faction, the Kharijites. Nineteen years later, in the Battle of Karbala, which marked the beginning of the Second Fitna of a total of six Islamic civil wars, Husayn ibn Ali, grandson of the Prophet Muhammad and son of Ali, was killed. All these bloody events, as well as numerous subsequent ones, paved the way for what is now called the Islamic schism, a discord with fatal and long-term consequences whose historical culmination, according to many analysts, was precisely the long-term proxy conflict between Saudi Arabia, probably the most influential and respected Sunni country, and Iran, which is the largest Shia country with a population of 87 million.

Now that the two countries are on the way to building a political alliance, there are probably ideal opportunities not only for the historical, religious, and cultural reconciliation of Sunnis and Shias but also for the confirmation of a fact that has long been clear to everyone outside the Muslim world, especially in the West, namely that Islam is one religion, not a group of religions. By the very essence of the foundations on which Islam was created, which are the original teachings of the Prophet Muhammad, this religion strives towards its final reunification, which is imposed by the force of logic by its universality, since it is the teaching of unity that was given to Muslims through the Prophet Muhammad and the Holy Koran revealed by the one and only God. If there is only one God, only one Koran, and only one Prophet Muhammad, then surely there can be only one Islam. The teaching that there is only one God (in Arabic, the word “Allah” simply means God) who is perfect in everything and the Creator and Lord of all worlds is the very core of Islam; it is called Tawhid and is a concept on which all Muslims agree. There is also absolute agreement regarding the teaching that the Prophet Muhammad was the last in a series of great prophets of the Abrahamic religions, including Musa ibn Imran (Moses) and Isa ibn Maryam (Jesus), and that he is God’s messenger, the seal of all previous God’s messengers to whom God revealed the holy book Koran. Despite this, some Muslims still lack the will to see the simplicity of the truth about the unity of Islam. First of all, there are certain differences in the Hadith, which are collections of Muhammad’s sayings that were initially transmitted orally from narrator to narrator. Hadith is not only the cornerstone of Islamic theology but also of Islamic jurisprudence and deals with practically all possible topics of religious, family, and worldly life on which the Prophet Muhammad gave his opinion, which ranges from tacit approval to strict prohibitions. Sunnis and Shias share a large number of identical hadiths, especially the most important ones concerning Muhammad and the traditions related to his personality, called the Sunnah, but there are also differences. Shias, for example, include in their hadith not only Muhammad’s but also the sayings of Ahl al-Bayt, Muhammad’s family tree, that is, his descendants. On the other hand, Shias reject the hadiths concerning Muhammad’s widow, Aisha, because of the civil war in which she took part on the opposite side of Ali. Islamic eschatology, the teaching concerning the end times, is based mainly on the Koran and the Sunnah, but here, despite the common fundamental beliefs, there are also different interpretations among the Shias and Sunnis precisely because of the differences in the hadith.

However, there is much more that unites Sunnis and Shiаs and makes them members of the same religion than there are religious teachings that separate them. They share virtually all fundamental beliefs such as Tawhid, the existence of angels, the line of prophets ending with Muhammad, the Day of Judgment, and Divine Predestination — the concept that God is omnipotent and omniscient and therefore has knowledge not only of everything that has happened but also of everything that will yet happen in the future. Both Shias and Sunnis celebrate the two biggest Muslim holidays, Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha, and at the same time too. Both observe the Ramadan fast (Sawm), follow the rules of almsgiving (Zakat), and believe that every Muslim who is able to do so must go on a pilgrimage to Mecca (Hajj) at least once in his life. They also adhere to the principle of Jihad, which is often and maliciously misinterpreted in the West. Prophet Muhammad explained that Jihad is primarily a spiritual struggle of Muslims against their own passions, sins, and temptations, and this is called “Greater Jihad”. In contrast, “Lesser Jihad” is fighting in the military sense, but here it is strictly a defensive war because aggressive warfare is strictly forbidden to Muslims. The declaration of faith, the Shahada, is basically the same for all Muslims. The believer declares that “There is no god but Allah, and Muhammad is the Prophet of Allah.” However, the Shias add another sentence to this declaration: “and Ali is the friend of Allah”, which they use to emphasize that he was the legitimate successor of Muhammad. As for the differences in the way Sunni and Shia Muslims pray (in Arabic salat; in Farsi namaz), they are really minimal. In fact, in many mosques throughout the Islamic world, Shias and Sunnis have prayed together for centuries, and of course, facing the qibla, the direction toward the Kaaba, in the Sacred Mosque in Mecca, Saudi Arabia. Despite the fact that there are disagreements about the identity of that person, another common belief of Sunnis and Shias is the anticipation of the coming of the Mahdi, the Messiah, who will bring justice and prosperity before the end of the world and, what is particularly interesting, also the unification of all Muslims. It is difficult to say whether it is precisely this belief that inspired the efforts to achieve Sunni-Shia unity, but they certainly exist and are numerous.

One of the first Shia clerics of modern times to advocate Islamic unity was Muhammad Taqi Qummi (1910–1990), who bore the Islamic honorific title “Allamah” meaning “learned”. He believed, first of all, in the cultural unification of Muslims, which could be achieved through the dialogue of scholars from different branches, schools, and movements of Islam and through education, which would develop and nurture closeness and mutual respect between Muslims of different denominations. In order to achieve this noble goal, Qummi founded The House of Proximity of Islamic Denominations (Dar al-Taqrib Bayn al-Madhahib al-Islamiyya) in Cairo in 1941, together with a group of Shia and Sunni scholars. Seeing clearly the importance of the consensus of all Muslims on the essential, fundamental principles of Islam, Muhammad Taqi Qummi believed that each community, at the same time, has the right to continue to act freely in accordance with the specific beliefs of certain branches and schools. Very insightfully, Allamah Muhammad Taqi Qummi emphasized that intellectual disagreements within Islam cannot be harmful but, on the contrary, beneficial, unless they lead to the breaking of brotherhood among Muslims. Qummi’s greatest achievement was that the famous and oldest Muslim university in the world, Al-Azhar in Cairo, Egypt, founded in 970, recognized Shia Imami jurisprudence. This would not have been possible if Qummi had not found the understanding of Sheikh Mahmoud Shaltut (1893–1963), who was then the head of Al-Azhar University and who was remembered for his efforts to implement a comprehensive reform of Islam. Sheikh Shaltut issued a special fatwa declaring the school and religious doctrines of Twelver Shi’ism, the largest branch of Shia Islam, as valid, and they have retained that status to this day. Another outstanding Sunni Muslim scholar from Al-Azhar University who became its Grand Imam in 1996, Muhammad Sayyid Tantawy (1928–2010), unlike modern Islamic radical extremists and militants, believed that every person who accepts the basic tenets of the faith contained in the Shahada is, beyond any doubt, a Muslim. On one occasion, Tantawy even said that there are no Sunnis and Shias but only Muslims, expressing his regret that the passions and prejudices used by some are the reason for the tragic fragmentation of Islam. Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini (1900–89), the first Supreme Leader of Iran and the founder of the Islamic Republic of Iran, was one of the greatest proponents of the unity of Shias and Sunnis. He often and publicly emphasized the oneness of the two major branches of Islam, claiming at the same time that it was the duty of every Muslim to cultivate such an attitude. His successor, Ayatollah Seyed Ali Khamenei, claims that Islamic unity is a Koranic obligation and that creating discord among Muslims is a great sin and therefore strictly forbidden. The highly influential Iranian-Iraqi Shia cleric Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, much like his Sunni counterpart Tantawy, considers a Muslim to be any person who pronounces the Shahada, follows the rules of some of the branches and schools of Islam, and does not show hostile feelings towards the Ahl al-Bayt, that is, to the descendants of the Prophet Muhammad. In addition to Al-Azhar University, there is another large and important institution that advocates unity and trust between Sunnis and Shias, and that is “The World Forum for the Proximity of Islamic Schools of Thought” (WFPIST), which was founded in Tehran in October 1990 by order of the Ayatollah Khamenei. This ecumenical society acts as a forum that actively works to reconcile all branches and schools of Islam, and to promote Islamic culture and bring together Muslim scholars and leaders, very similar to the teachings of Qumma. During the founding of WFPIST, Ayatollah Khamenei contacted Muhammad Taqi Qummi, and he welcomed the decision to establish that forum and intended to participate in its work, but he was prevented from doing so by his tragic death in a traffic accident on the streets of Paris.

One of the most terrible consequences of the proxy conflict between Saudi Arabia and Iran, and in general, the intolerance between Sunnis and Shias, is the birth of the so-called Islamic State, or Daesh, as it is called in the Arab world. The Islamic State was founded in early 2014 by radical Sunni militants who joined forces ten years earlier in Iraq to fight against the American invasion. At the time, these groups operated under the umbrella of Al Qaeda, but instead of focusing on fighting a foreign invader, they waged war against Shia militias and later even against the Iraqi government itself. When the civil war broke out in Syria on March 15, 2011, Daesh used the opportunity to expand its activities from Iraq to the territory of Syria and soon began the terrible slaughter of Shias, Yazidis, and Christians. The Islamic State has directed the most unbridled hatred towards the Shias, their Muslim brothers. The crimes of Daesh extremists multiplied at such a speed that even U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry called it genocide in 2016. The ideology that inspired the creation of the Islamic State is a radical, twisted, and militant version of Salafism that the vast majority of Salafists do not practice. With their extremism, Dash fighters have unfortunately overshadowed all their predecessors from other similar terrorist organizations. They became the most fanatical advocates of Takfirism, an ideology that is contrary to the teachings of Islam and whose essence is sectarianism, which declares members of all other branches and schools of Islam to be apostates from their faith. The ideologues of the Islamic State, although representatives of a distinct minority in the Islamic world, declared themselves to be the only orthodox Muslims and decided to kill all others on the charge of being apostates. This is in stark contrast to the simple definition given by Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani and Muhammad Sayyid Tantawy that a Muslim is any person who recites the Shahada and respects the Ahl al-Bayt. Since traditional Islamic law does provide for the death penalty for apostasy, baseless and false accusations of this offense are considered a forbidden act (haram). The Hadith clearly states that one who falsely accuses other Muslims of apostasy must himself be considered an apostate from Islam. Finally, in the Koran itself, Surah Al-Mu’minun (The Believers), verses 52 and 53, this time in the Words of God Himself, clearly confirm that all those Muslim believers who read those verses are members of the same religion. Verse 52: “And indeed this, your religion, is one religion, and I am your Lord, so fear Me.” Verse 53: “But the people divided their religion among them into sects, each faction, in what it had, rejoicing.” Muslim scholars are of course aware of these Koranic verses (ayat), which are a key theological argument against sectarianism, and it becomes clear why many of them increasingly consider the unity of Muslims to be a Koranic obligation. However, the mass crimes carried out by Daesh in the name of Takfirism are only part of the big problem that this terrorist organization represents not only for the Greater Middle East region but for the entire world. Dr. Nafeez Mosaddeq Ahmed, a British investigative journalist, came across direct and indirect evidence nine years ago that the U.S. and the UK were financing the Islamic State through secret channels and intermediaries in the Middle East. Ahmed followed money flows, public documents, and statements from American and British officials and probably dug much deeper to finally expose the two-faced Anglo-Saxon game and finally reveal his findings to the world. On the one hand, the Americans were officially waging a war against Daesh, and on the other hand, that war gave them an excuse for a permanent military presence in the region and looting Syrian and Iraqi oil. Likewise, the Islamic State was necessary for the Americans and the British, and not only them, in order to destabilize the entire region and remove Bashar al-Assad from power in Syria because of his strong ties with Russia and Iran. In 2016, Efraim Inbar, an Israeli professor of political studies from Bar-Ilan University and director of the Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies, rather carelessly admitted that Israel is also a deeply involved party in the Syrian conflict. He openly protested because “the West was destroying Daesh,” seeing the existence of the Islamic State as a barrier that would stop “Iranian hegemony” in the region. With that, he admitted what we all always knew, which is that Israel is no less than an ally of Daesh, and that was actually, more than visible on the ground during the battles. This also explains why the terrorists of the Islamic State did not carry out a single attack against Israel, the greatest enemy of all Muslims. The leaders of the Islamic State, of course, knew very well what they were doing and for whom they were working, but the big question is whether the ordinary fighters were aware that their religious feelings were being grossly manipulated and that they were not only killing innocent people, which is one of the greatest sins in Islam, but also serving the enemies of Islam. If Saudi Arabia and Iran had been able to move from détente to entente much earlier, the Islamic State would never have existed, and the lives of hundreds of thousands of people would have been saved. We can only hope that the Great Reconciliation of the Middle East will lead to the extinction of Daesh and the permanent annihilation of their monstrous ideology that has nothing in common with what Islam really is.

This historical moment could be remembered as a great turning point in which Muslims will forever reject the darkness of Takfirism and religious hatred in favor of the idea of a new Golden Age of Islam that will illuminate the entire planet with its wisdom. It is of great importance not only for Muslims but also for the rest of the planet, which is fed up with American hegemony, neo-colonialism, and imperialism. Islam is a natural bastion of traditional values, conservatism, anti-liberalism, and, if you like, anti-Satanism, and as such, but only under the condition that it is united, it represents an insurmountable obstacle to the further expansion of the collective West. Those who, under the influence of the Hollywood propaganda machine, are panicking about the possible unification of Islam, fearing that it will be something similar to the Anglo-Saxon creation of the Islamic State, should remember that historical experience so far has shown that Islam is dangerous for the rest of the world only when it is disunited, and again, the best illustration for this claim is the Islamic state. These days, Saudi Arabia and Iran are proving that the political unification of Islam is possible, even though the collective West has convinced us for decades that sectarian hatred and conflicts among Muslims will last until the end of time. The cultural unification of Islam that Allamah Muhammad Taqi Qummi talked about is certainly possible, but its religious unification is also not only possible but necessary on the basis of the Koran itself, as emphasized by Ayatollah Khamenei. The formula for the unification of Islam that Qummi gave is really simple and requires only a little good will in order to be realized: let us make a consensus about what the common beliefs are, and there are really many of them, and let other Muslims exercise in peace the specific practices of certain branches and schools of Islam — in short, tolerance. In this way, in fact, Qummi laid the foundations for not only cultural but also religious unification of Islam, although he may not have been aware of it at the time.

Have Muslims finally learned the historical lessons from the decades of colonial and neo-colonial rule, and the terrible suffering they have endured since the beginning of the 1990s until today? The Gulf War, the “War on Terror,”, the Iraqi wars, the Arab spring, the Western military interventions in Libya and Syria, and other civil wars in the Greater Middle East have clearly exposed the collective West’s plans for “the final solution to the Muslim question,” similar to the plan to destroy Orthodox Christianity. There are many indications that Muslims are fed up with the rampage of the collective West against them, and that there is a rising awareness that only by being united can they preserve freedom and peace. One of the 99 names of God in Islam is As-Salam — The Giver of Peace. In the Koran itself, it is emphasized in many places that Islam is a religion whose one of the most important characteristics is the search for spiritual peace and peace among people. When Muslims greet each other, they do so as the Koran instructs them to do: “As Salam Alaykum” translated from Arabic means “Peace be upon you”. Islam is truly a religion of peace, and its followers deserve an age of peace and progress. In order for Muslims to finally achieve this, it is very important that they reject the image created about them by the Western propaganda machine, to which many of them have succumbed. Islam is not, as the collective West would have us believe, some huge, menacing medieval fortress from which blood pours from severed heads that adorn its ramparts, while from the dark depths of its icy dungeons come eerie cries of pain. No, Islam is a slender and elegant palace, an architectural perfection that, scraping the sky with its height, shines under the sun, moon, and stars with a golden glow that stretches to infinity. The Palace of Islam is, in fact, one great university whose broad windows look out on all sides of the world, filling it with the light of knowledge and peace. On the shelves of its spacious libraries, we can find books with the teachings of Muslim clerics and theologians of all existing branches and schools of Islam of all eras, but also much more than that. In the Palace of Islam, that metaphor of its true essence, knowledge from the pre-Islamic period and books written by famous Islamic philosophers, theologians, mathematicians, physicists, astronomers, and doctors are preserved. Let us recall those great men such as Alkindus (Al-Kindi), Alpharabius (Al-Farabi), Avicenna (Ibn Sina), Algazelus (Al-Ghazali), Averroes (Ibn Rushd), Sohrevardi (Suhrawardi), Asterbadi (Mir Damad), and Sadr ad-Din Muhammad Shirazi (Mulla Sadra). Today, all Western scholars agree that without the universal creative oeuvre of these polymaths, through which they exerted a strong scientific and cultural influence on Europe, there would never have been a Renaissance or a modern European civilization. The roots of the ingeniousness of those and many later Islamic thinkers were in their devotion to peace, spirituality, knowledge, and progress — and that is the authentic face of Islam that the world will soon see again.