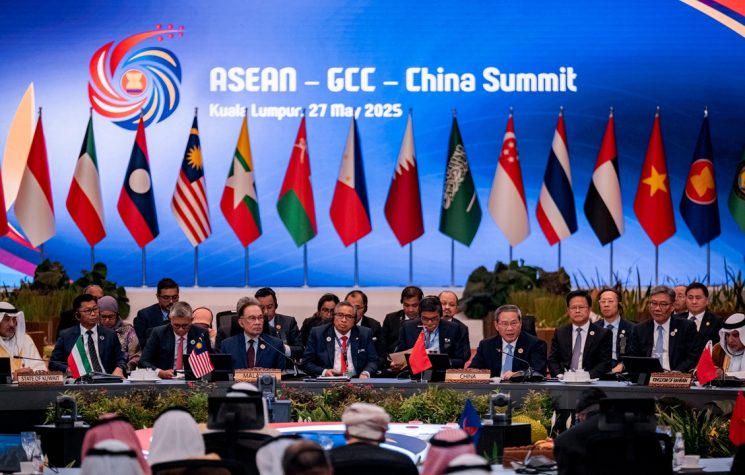

China has a chance to transform the world for the better. Though it is no open goal, she should take it to take her place in the van not only of BRI but of the nations of the world, which is at her feet.

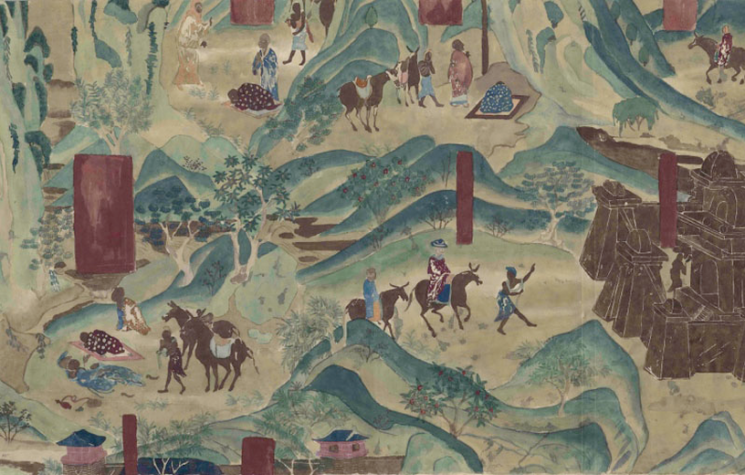

This article looks at the wider implications of NATO’s defeat in Ukraine and, in particular, how it has set the ne plus ultra to the march of the World Economic Forum’s Great Reset and thereby guaranteed the success of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and so helped set the world’s economic trajectory for the next century.

The article superimposes, for exemplary purposes, BRI’s spatial model on the Japanese logistics system, before analyzing how BRI can accommodate Taiwan, Japan and Korea, the three Asian spokes of America’s over stretched East Asian hub system. It then conducts a summary SWOT analysis and, crucially, concludes by outlining how the emerging financial system of China and allied countries can underpin all of this.

Though it is an ambitious exploratory piece, it helps lay out the parameters of BRI’s New World Order (NWO) and juxtapose it with the now redundant NWO plans of the WEF/NATO axis. This piece is, in sum, a précis of the economics of our next 100 years.

Sino-Japanese Spatial Networks

Japan’s transport system is an integrated network of trains and tunnels and the Japanese are, by far, the world’s best tunnellers. Japan not only pioneered the bullet train but their vast rail networks remain at the center of their economic success. Put simply, the private companies which partly own those networks recoup profits by building shopping and other complexes around their lines. Theirs is a well thought out logistical system, which continues to reap dividends for all Japan’s stakeholders.

BRI must be similar. It must be well thought out from Papua New Guinea to Syria and it must bring benefits for all stakeholders, from the China Pakistan Economic Corridor and from the Solomon Islands to the Russian-Finnish border. It must, in essence, continue to evolve into a much larger and infinitely more complex but no more sophisticated extension of that Japanese system.

The Japanese merchant fleet adds up to approximately 120 million gross tonnage, making it one of the world’s largest fleets. This superlative armada is, in essence, an extension of Japan’s domestic networks, forced on it by America’s earlier gunboat diplomacy. BRI’s must be no different. It must be a series of integrated networks that can move products at any juncture between the Solomon Islands and St Petersburg and from Jo’burg to Shanghai whilst providing work, opportunities and increased living standards for all stakeholders along the way.

Although Chairman Mao’s iron rice bowl of womb to tomb security is no more, there must be, as there has been in China, not only cascading trickle down effects but the growth and consolidation of new hubs in Africa as much as in Asia. Thus, although Japan was up to recently the world’s leading auto maker, China, India and South Korea have gnawed into that market share as, in this age of product differentiation, Japan’s auto makers cannot be all things to all customers just as Hollywood, Bollywood and Western fashion designers cannot be in their own rent-protected fields.

Although Japan must now share, the key take away point is Japan has solved much of its logistics and supply line issues in auto making as much as in quick buck areas like fashion, Samurai movies or tourism. Materials are trucked or trained to Osaka and then are shipped overseas as Toyota Corollas; J Pop and Hello Kitty, meanwhile make their own considerable mega billion dollar inroads. As domestic costs have risen, Japan has outsourced much of their assembly work to Thailand, Malaysia and the United States, all of which have benefited from Japan’s organizational genius. China, unless she self immolates, is Japan on a much wider and more accelerated canvass.

Besides learning how to make the bullet train from Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, China has learned much not only from Mitsubishi but from the zaibatsu and keiretsu systems that Mitsubishi still anchors. Whatever challenges Mitsubishi might have faced since America’s black ships first invaded Japan’s home islands, finance was not one of them.

Put differently, no matter what projects Mitsubishi sets itself, financing them and reimbursing their stakeholders are not a concern. Picking what projects to finance is the key with Mitsubishi, as it should be with all of BRI’s partners, both big and small. Because Mitsubishi is so big, it has thrived, like a Sumo wrestler, within the small confines of Japan, whilst also prospering overseas and, equally, while always conforming to Japanese contractual norms which favor the long term over NATO’s shorter smash and grab vista.

The issue with joint ventures of the sort that underwrite the nuts and bolts of BRI are which partners are to do what, where are the demarcation lines, which contractual norms are to be followed and how can Anglo American disrupters be kept at bay. These issues, which we now address, are no trivial problems.

Korea, the Dagger at Japan’s Heart

For China, Japan, Korea and all of Eastern Asia to plough ahead, all East Asian BRI partners must consign American stoked territorial and historical enmities to history’s back burner. Though China, Japan and the two Koreas must agree to disagree, diplomacy remains Japan’s weakest card. She is too beholden to the USA just as she was formerly too beholden to Britain and Nazi Germany. Japan must solve her territorial disputes with Russia to the North and China to the South, whilst also putting the Korean issue to bed once and for all. These are best done by each side living within their own myths, by diplomatic and economic cooperation, by means of an amended BRI, not by lobbing nuclear missiles at each other and anyone else who wants to be obliterated.

Mirroring her claims to the Spratly Islands, China claims that the Senkaku Islands between Okinawa and Taiwan have been indisputably Chinese from as early as 1372! Beijing claims that Japan has been a mere interloper there. As the victor in the 1894-95 war with China, Japan seized those islands along with Taiwan and the Penghu Islands and incorporated them into Okinawa Prefecture as Japanese territory. China intends to prise them back. Mirroring her war of nerves against Taiwan, China has conducted missile tests in the waters off the Senkaku Islands and, unless Japan properly asserts herself, China will most likely regularize this tactic over time as well. China lodges strong diplomatic objections any time Japanese officials visit the islands and her military research vessels continue to encroach on Japanese waters around the islands. Though the Senkaku Islands is, in other words, another Spratly Islands or Taiwan in the making, neither Beijing nor Tokyo needs this additional American inspired grief; they both have much bigger fish to fry.

China says that Japan’s claims are based on its victory in the 1894-5 war and that its defeat in the Pacific War negated those claims. Though the Cairo Declaration jointly issued by China, the United States and Britain during World War II stipulated the return to China by Japan of all the territory she had annexed during and after the 1894-5 war, those islands are none of NATO’s business as they are at the other side of the world.

The PRC claims that forfeiture of these islands were implicitly included in Japan’s surrender; they were not explicitly included. China argues that the Cairo Declaration and the Potsdam Proclamation, which affirmed it, make those islands Chinese. The Chinese claim Kume Island to be the beginning of Japan’s Ryūkyū territory and of Okinawa Prefecture; the rest of them, Beijing claims, are theirs alone. China claims that, prior to the 1894-5 war, the entire Ryūkyū Islands paid tribute to China and were therefore Chinese. China, in other words, claims all the islands between Taiwan and Okinawa as Chinese and says that Okinawa is probably Chinese as well.

China’s claims over the Senkaku Islands cannot be dismissed out of hand. These islands have considerable emotional appeal to Beijing’s leaders. China sees the capture of these islands by Japan’s imperial forces at the end of the nineteenth century as heralding her own fall and Japan’s consequent rise. The annexation of these islands was the beginning of the Japanese empire – and of today’s enmity between Japan and China. After the Ryūkyū Disposition incorporated the islands into the Okinawa Prefecture, Japan then forced Korea to sign a treaty and open its ports for trading. This paved the way for Korea’s annexation, Japan’s rise to power and China’s consequent demise.

Crucially, however, much of Imperial Japan’s Korean excesses can be traced back to European machinations on Japan, which tried to impose her own Emperor on Koreans, who historically regarded only the Chinese emperor as deserving of that type of homage and who therefore regarded Japan’s claims to have their own emperor as, at best, churlish.

The War of JiaWu began in July 1894 between China and Japan to achieve hegemony on the Korean peninsula which, as it remains a dagger to Japan’s heart, must be delicately dealt with. The JiaWu war ended with the parties signing the Treaty of MaKwan (Shimonoseki) on April 17, 1895. Defeated, China was forced to pay a huge indemnity of some 350 million yen. Because this large sum dwarfed the then Japanese national annual income of 80 million yen, it allowed Japan achieve economic lift-off. China’s silver and gold was used to boost Japan and further cripple China. The Senkaku Islands’ defeat fueled Imperial Japan’s overseas adventures and helped emasculate China at the same time. This is not something China can lightly forget. It was as integral to China’s century of shame as were Anglo America’s Opium Wars, themselves a terrible indictment of the rape of China by foreign imperial powers.

This victory put Japan well on the road to achieving the hard power of military and economic force, which were the international currencies of the day. China’s massive reparations paid for the Yahata Steel Works, the first modern factory built during Japan’s Meiji era. This was the basis for Japan’s considerable armaments industry. Japan also built its modern railway structure, which further served to unify it. China didn’t and paid the price in military terms for it. Japan’s decisive victory effectively destroyed China’s hopes of hegemony not only in Korea, but also in the entire region and thereby shaped the futures of both countries up to Japan’s August 1945 surrender. Although history could conceivably have been different, Japan’s better organization set the parameters on the march of both nations over the next half-century.

Peace meant that China had to surrender the Liaotung Peninsula, Taiwan and the Pescadores to Japan. Liaotung cemented Japan’s hold on Korea and Taiwan provided strategic bases for the Japanese navy. Taken together, they gave Japan the scope for its further expansions, which only further weakened China. This process continued until the wholesale eruptions, which followed the 1937 Marco Polo Bridge incident and ignited the eight-year war between the two nations. The eight-year war further deepened China’s hatred of Japanese involvement on Asia’s mainland.

Though both adopted the “rich country, strong army” slogan at the end of the nineteenth century, only Japan turned the rhetoric into reality. Japan increasingly dominated China economically. It accounted for almost 40 percent of its trade deficit. Japan’s China conquests also allowed it to emerge as a world power, which the European powers had to respect. The European powers abandoned their unequal and unenforceable treaties with Japan and allowed her access to their markets. China, by contrast, continued to be ravaged. The Great Powers, with Japan playing an increasingly large part, continued to milk China dry until the end of the Great War, when Japan and the United States were left with the field almost entirely to themselves.

Though important lessons must be learned from all of that, Sino Japanese enmities must be consigned to the past because BRI, to achieve its potential, must eventually wrest the Korean, Taiwanese and Japanese spokes from the United States’ hub, which would otherwise use them as spanners in the works just as they used such weaknesses against both Japan and China in the past. If BRI is to achieve its potential, it must overcome the tyranny of history and wrest America’s three East Asian spokes of Taiwan, Korea and Japan from out of the NATO/Five Eyes’ claws.

Pre BRI Finance

Recent global financial markets were, like ancient Gaul, divided into three parts. The American markets had the technology, the Japanese had the money, much as Australia or New Zealand have wool, and the deals would be done in London. The German block, meanwhile, was an industrial powerhouse, bankrolled by German, Swiss and Middle Eastern finance, stymied only by a lack of access to the markets and raw materials east of Vienna.

The situation now is that though Japan still has the money, so too do the insurance, re-insurance and banking companies of China, India and a number of other BRI countries. Their American technological problem is how to tailor it and add value, as the Italians do to to the ANZACs’ mountains of wool. The answer to that, as previously discussed, is in developing and deepening BRI’s Russo-Sino-Japanese spatial networks.

These networks are important to ensure that BRI money continues to go to where it is needed and to where it can be more productive both on the macro scale that Mitsubishi represents and on the more speculative venture capital side that is more typical of Hollywood, Silicon Valley, tourism and bio tech companies.

This is, in essence, the Long March of Chinese finance where BRI must not only deliver on the macro projects but on the more micro and niche ones as well. For that, China and her allies must have a financial system as robust, deep, flexible and all encompassing as is that of the Anglo American Dutch system.

Macro and Micro Projects

Because BRI’s macro project are already gaining traction with trade booming between Russia and China, the devil is in BRI’s micro successes, which revolve around true trickle down effects and concomitant opportunities for entrepreneurs from St Petersburg to the Solomon Islands. Examples of such micro successes could include the reconstruction of Syria and Iraq, supplanting Coca Cola, Fanta and similar frivolous products, financing BRI cultural projects and challenging Brand NATO, Big Pharma and Wall St’s other sweet spots.

China can help rebuild Syria by providing the necessary financial lubricant to get her markets going again. Syrian farmers cannot plant or harvest crops because they do not have the necessary finances to do so. Hoteliers, house builders and similar Syrian entrepreneurs are in broadly similar situations. China, taking the longer term Japanese outlook, can solve much of that by bankrolling local Syrian initiatives and, as Japan post War did, by subsidizing with social credits those who bled for Syria to reduce end consumer costs and to fit Syria’s economic trajectory within longer term, attainable goals. As payments would, in part, be made in kind, the system would not be that different from that which cash starved Japan utilized from the August 1945 surrender up to the 1964 Tokyo Olympic Games when former Imperial soldiers, still in their field uniforms, were to be found begging, permits in their pockets, on Tokyo’s Ginza.

China’s Syrian challenge is to reset the cradle of Western civilization on a new cooperative trajectory that serves Syria’s stakeholders, rather than those who set out to destroy Syria. Restarting the Armenian orchards and soap factories of Kessab, to take one illustrative example, is not a daunting task, if one has the necessary Chinese financial and other logistical expertise to do so. China getting an economic as well as a social return on its Syrian investment is not a daunting task if China helps put Syrians on a permanent and pensionable trajectory where they can repay China’s investment. As Russia rebuilt Chechnya, so also can China help rebuild Syria as part of BRI’s nodal system.

Of course, there will be setbacks just as NATO’s criminal sabotage of Nordstream 2 was a setback but a carrot and stick system, of rewards for Syria and stiff penalties for disrupters would go a long way to solving such issues over the longer term that Japanese companies concentrated on and always felt more contractually bound to. The Chinese might be better off dealing with countries like Syria that NATO have recently ravaged, rather than countries like Germany which abandon mega billion projects like Nordstream on the whim of their masters in Washington and their court clowns in Kiev.

Whereas NATO’s terrorist campaign has lowered Syrians’ expectation somewhat, others who have yet to suffer at the hands of NATO’s military are understandably perched further up the tree of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. The younger amongst those fortunates crave NATO’s carbonated soda, Netflix and Uber taxi rides, whereas the older prefer Botox, Big Pharma’s products, French artisan bread and endless virtual circuses. All of those sweet spots are vulnerable to Chinese funded BRI entrepreneurship.

All Coca Cola and Pepsi have going for them are their massive budgets, which have helped them buy U.S. Presidents for the last 80 years. As there is nothing otherwise unique or special about their products, they are easily replaced. Fanta was invented by the Fantastic Cola Company, a Coca Cola off shoot in Nazi Germany, as the Reich lacked sugar. Scotland is the world’s only country where Coca Cola is not the best selling soft drink. That is a result of the massive publicity Irn Bru, a Scottish company that sells its own sugar soaked swill, does. There are hundreds of other colas in the world and one of the reasons the USA originally sanctioned India was because India wanted to replace Coca Cola, which uses far too much of India’s scarce water supplies, with Indian products which were every bit as good.

Although British billionaire Richard Branson saw a huge gap in the global market when he launched Virgin Cola, he failed because of the incomparable strength and thuggish ruthlessness of Coca Cola’s marketing division. But that is all NATO is, carbonated water and snake oil salesmen and, if BRI cannot outclass that, they are a sorry lot. Given that Coca Cola has long tried to get young Chinese and Japanese to switch from green tea to Coca Cola, China is in pole position to swat that fly and open the door for healthier Chinese, Indian and Japanese alternatives.

Much the same goes for Hollywood, America’s version of Bollywood. China’s film industry has now come of age. Chinese films now out gross Hollywood’s in China and China now has her own Rambos, Jack Sparrows, Jackie Chans and Terminators and so on to grace their own silver screens.

China has a great opportunity to launch joint cinematic projects with Iran, Nigeria, South Africa, Thailand, the Philippines and its other BRI partners, who have robust domestic film industries but lack China’s financial fire power to bring them to the next level. As well as being a significant display of Chinese soft power, these joint projects would offer all kinds of opportunities for product placement, which is one of Hollywood’s many blights.

One of the easiest such plots might involve Jiang Wen and Ning Jing getting involved with the Bolshoi, enjoying Beluga caviar with Beluga Gold line vodka, as Irina Starshenbaum chases them in a Lada Granta through Red Square in search of The Rasputin Code. Let’s just say that though such a BRI film would make up in increased Sino-Russian tourism what it might lack in plot, because a lack of any originality has never hindered Hollywood or the more endearing Bollywood for that matter, it should present no difficulties to Sino-Russian, Sino-Thai or Sino-Nigerian projects cut from the same cloth.

On a recent visit to Kraków airport, I was delighted to see that only Polish alcohol, including relatively expensive Polish wines, were for sale; if folk want to buy alcohol in Poland, let them buy Polish alcohol. If BRI movies can help get Chinese consumers to choose BRI wines over French wines and BRI cheeses over their French equivalents who, besides French cheese makers, can complain about that? The BRI countries could play the old Japanese import substitution trick that BRI palates can only handle Russian, not French cheeses and wines. If it worked for the Japanese with food, snow skis and baseball bats, why not with the BRI countries?

Crucially, for our purposes, such cultural projects could be financed much as Hollywood’s efforts are, by a series of Lloyds type names and by collecting additional revenues through product placement, a not inconsiderable factor when we consider the business of sport.

Firms like Decathalon have been able to significantly undercut Nike and Adidas by designing their own products and not sponsoring super stars to pimp them. BRI can take this a step further by having intra BRI games at all levels, much like Israel’s Maccabi Games or, in fact, somewhat like the Kerry Packer’s World Series Cricket, which severely disrupted that sport of empire.

Iranian-French chess grand master Ali Ferozja exemplifies. Ferozja fled Iran for France because the Iranian Chess Federation banned him from playing against an Israeli chess player in a 2019 tournament held in Russia of all places. Now France forbids Ferozja to play against Russia, which is the heart and soul of chess.

Although NATO enjoys punishing those who don’t compete against Israel just as they punish those who do compete against Russia, the best must compete against the best, no matter what their nationality. NATO’s selective terror campaign against not only Russian but all sport has left a gaping hole in the market that might, in time and with BRI financing, be the undoing of both Nike and Adidas as well as the International Chess Federation, whose major sponsors include Gazprom, Nornickel and Phosagro, all three of which are major Russian companies NATO currently badly needs and all three of which should consider extending sporting and chess scholarships to BRI countries for aspiring African athletes and chess players who might, in time, pit their wits against Ali Ferozja, if France wills it.

As in the high risk business of sport, so also with J-Pop, K-Pop, Cantop and their manifestations in fashion and other supposedly high risk areas. Not only have such carefully contrived genres replaced much of NATO’s cultural baggage but they show that BRI’s youth do not need the tens of billions of dollars worth of Gucci and Louis Vuitton accoutrements, which Italy and France so relentlessly pimp at both China and Japan and which, as Japan’s own artisans, who can easily match NATO in terms of quality, can tell you, have only their European brand names to artificially sustain them. BRI pop and “BRIwood” have the potential to change all of that by changing what is fashionable and what is not. Though China, Japan and Korea have so many home grown influencers that Hollywood and its clones are now superfluous to their advertizing and marketing campaigns, the key to their post war success was to be found in hard industries, not in the more mercurial worlds of Hello Kitty, Hollywood and J-pop. Because China’s purchasing power has the raw financial muscle to make high end fashion a BRI rather than a Gucci, Prada or Burberry thing, NATO should take note.

Rents, Education and Venture Capital

BRI would bestow economic rents, steady streams of income, on its main stakeholders, just as Japan’s railway system does to its financiers and that is how it should be. In addition to that, venture capital firms could speculate around that framework without unduly disrupting it. BRI, like Japan’s railway system, or indeed like Japan’s Edo era, would be a period of stasis affording the springboard for those so inclined to engage in more medium to high risks ventures with their own capital while not putting the overall framework under strain.

BRI could also learn from the Japanese educational system where firms like Mitsubishi, who are at its core, scoop up Japan’s best to work for them. To phrase that differently, BRI must examine how best to deploy their sizable student populations. Were the Chinese to abandon British universities for greener and more relevant pastures, the British educational system would collapse and the same applies to many of Albion’s former colonies.

That approach to education is akin to Japan’s traditional approach to tourism where Japanese workers were encouraged to honeymoon in Hawaii or American occupied Guam to help offset the considerable profits Japan was gleaning from America. If BRI were to fully replace the Anglo American and Five Eyes’ universities with their own, that could only benefit BRI’s youngest stakeholders as well as their future employers and that process could be much accelerated if a more humane form of Sallie Mae, Fannie Mae or Britain’s usurious student loan system was utilized. The best way of achieving that is to involve Gazprom, Nornickel, Phosagro and other STEM focused BRI firms at the heart of education.

SWOT

Although we’ve touched on some of BRI’s strengths and weaknesses as well as the opportunities BRI offers its stakeholders, NATO’s threats must not be under played. As well as NATO’s Ukrainian, Syrian, Iraqi and Yemeni terror campaigns, China must now counter Canadian attack planes threatening the North Korean coast. Clearly, China and North Korea would not only be well within their rights in permanently neutralizing such threats but, whether it’s Canadian aggression off the Korean peninsula or Canadian inspired Sinophobic terrorism along the Sino-Pakistani corridor, they might actually be doing peace campaigners worldwide a favor by taking the appropriate actions.

On the soft war side of the ledger, in addition to The Economist sowing dissent in China, it has much too much to say on China’s role in Africa, which is a lot nobler than The Economist’s own 150 year long Afrophobic campaign waged under its colonialist free trade of else mantra that was previously manifested, inter alia, in their Chinese Opium Wars and Japanese Black Ships’ campaigns. Its superlative use of English aside, the Economist is of no practical use beyond that of the compost bin.

Much the same goes for insurance and the other invisibles London offers. The English did not invent insurance: the Chinese and Vietnamese practised those arts when they divided their cargoes into different sampans paddling down the Mekong and the Yangtze thousands of years ago. Though insurance has moved on from those halcyon days, so too have the Chinese and Vietnamese insurance industries ,which do not need London brokers poncing for business. If Russian, Syrian, Iranian or other ships under NATO’s sanctions need insurance or re-insurance, China and her allies can supply it and, if necessary, a blue water navy to protect them as well.

Externalities

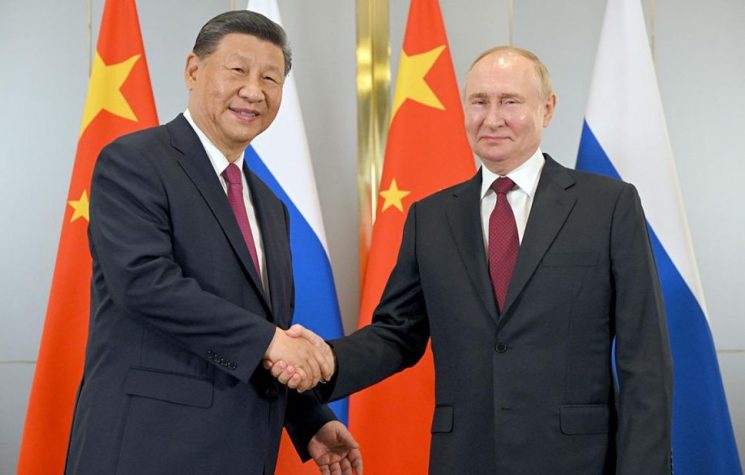

Russia, like Afghanistan, seems to be the graveyard of empires. Within an eye blink, we have seen Uncle Sam cut and run from Afghanistan and we have seen the Russian armed forces stop NATO’s gallop in Ukraine, just as they previously saved Syria from imploding.

NATO’s race is run. Their larder is bare and all they have to show for it is their most recent booty from Afghanistan and the Fertile Crescent. As they care not a whit about the tens of millions who died as a result of their wars, why should we believe those serial killers care a whit about the environment? They do not. NATO’s only god is Mammon and it must be shunned like the pariah that it is as a consequence.

China has a chance to transform the world for the better. Though it is no open goal, she should take it to take her place in the van not only of BRI but of the nations of the world, which is at her feet. Though she can continue to learn from Japan’s earlier blunders and she can continue her crucial alliance with Russia, she must keep her eyes fixated firmly on the prize of completing today’s Long March of anchoring the financing of a NATO free network from Brazil to Beijing, from the Central Pacific to St Petersburg and from South Africa to Siberia.