Japan’s future, whether she likes it or not, will be with its East Asian neighbors’ Belt and Road Initiative when the U.S. 7th Fleet scuttles back to Pearl Harbor.

Although it is now 20 years since the English edition of my Japan: The Toothless Tiger best seller first appeared, everything that has since happened has confirmed its thesis that East Asia is a powder keg that Japan cannot contain.

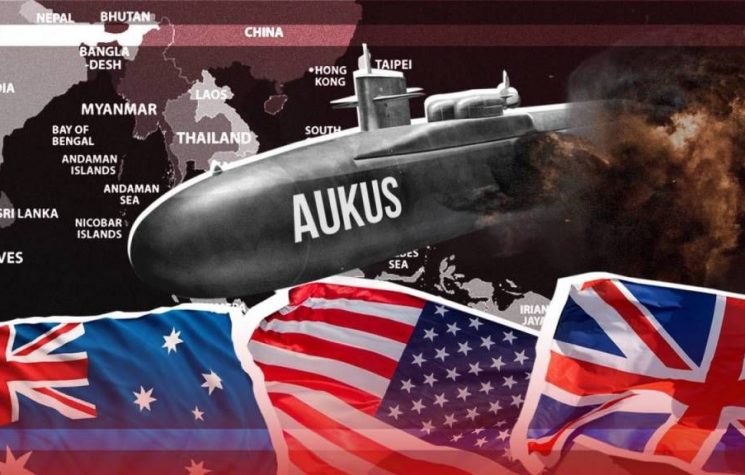

Although China’s Belt and Road Initiative is inexorably falling into place, so too is the South China Sea. Although a British convoy, supported by German and American cruisers, recently sailed through the area, they, like the Australians, who are being butt hurt by Chinese sanctions, are not serious players.

South Korea, Taiwan and Japan are the region’s heavy hitters. Though Taiwan would give an excellent account of itself in any future encounter, there is little they could do when faced with overwhelming Chinese firepower. Taiwan could be East Asia’s Arch Duke Ferdinand moment.

South Korea, however, remains the real dagger to Japan’s heart. There are more than five million men under arms on the Korean peninsula – far more armed soldiers than either the United States or Russia maintains. Vladivostock, Russia’s military headquarters in the Far East, is only fifty miles away from North Korea! The resulting geostrategic rivalries make Korea the most militarized piece of real estate on the planet and it is the only place the United States has (repeatedly) declared it has locked and loaded nuclear weapons. As there is no way Seoul can be defended from a determined attack, the USMC is heavily embedded in Okinawa to where they hastily retreated at the height of the Korean War and to where they most likely will have to retreat again. Though Japan needs South Korea as a buffer state against North Korea and its historical Russian and Chinese sponsors, the Belt and Road Initiative would marginalize Japan and make her almost irrelevant to this Chinese minted version of The Great Game.

China views its own naval expansion as vital to protecting her sea routes and, just like Washington, Beijing is deploying her navy to ensure that the black gold continues to arrive to her shores. The fact that this policy poses a threat to Japan is not Beijing’s primary concern. They have the much more daunting task of keeping their vast nation afloat. For that overriding purpose, they need a strong navy to guarantee their oil supplies and a steely determination to defend and promote their national objectives.

Japan’s looming quandary is that, with Taiwan and South Korea, it has been a vassal of America’s East Asian policy, trading economic advancement for American political and military hegemony in contrast to China’s unfettered development. That bill is now due.

China is involved in a great strategic game that she cannot afford to lose. Kazakhstan is China’s natural bridge to the lucrative Iranian and Iraqi fields. Such a link-up would advance China’s standing as a world power. It would also cripple United States’ efforts to secure the Caspian Sea’s oil for the West. China also wants to secure central Asia’s economic cooperation to help mollify Xinjiang, which Erdoğan’s Muslim Uighur fifth columnists are charged with subverting. About 200,000 Uighurs live in Kazakhstan and opposition Islamic terrorist groups have their bases in Almata, its largest city. China hopes to neutralize this U.S. sponsored internal ISIS threat by its oil diplomacy in Kazakhstan, and its arms diplomacy in Pakistan, Iran and Iraq.

NATO’s ongoing belligerence in Eastern Europe has transformed the pipeline poker China has been playing with Russia and the other regional powers, forcing Russia and oil rich Kazakhstan to fully throw their lot in with China. Siberian oil will flow southwards to China and, if Korea and Japan wish it, onwards to them as well.

Iran meanwhile, is helping China wrest the vast oil reserves of the Caspian Sea and the Persian Gulf from Uncle Sam . If Iran and China control the flow of oil from the region, the United States will lose control not only of the Caspian Sea but also of the Persian Gulf’s vast and vital oil supplies. Japan best urgently take stock.

China’s missiles nullify America’s capacity to militarily dominate Asia’s vast geography with its small, dispersed pockets of marine forces, whose forward deployment policy bases are much too vulnerable. Without forward bases in Asia, there can be no concentration of American military power: weapons cannot even be stored, let alone massed for use.

This vulnerability of their bases to Chinese missiles is America’s singular military weakness in Asia. America’s powerful Seventh Fleet cannot make up for the loss of Asian land bases. The Seventh Fleet cannot generate anything like the military power or psychological effect of fixed bases.

The most important of these forward bases are those in Japan. Guam, like mainland America, is simply too far away to fill this role. Okinawa is the pivotal, preferred spot. And China’s missiles are gradually making those bases redundant to America’s strategic thinkers.

China is devoting vast resources to her missile program. This is a war of nerves where time and, ultimately, technology, is on the side of Mainland China. This psychological aspect explains China’s widespread use of ballistic missiles, which are, in essence, really psychological weapons – paper tigers if you will. Although Taiwan might protect itself from an amphibious assault, protecting Taipei from surgical missile strikes – or the threat of surgical strikes – by Beijing’s ballistic missile units is a more daunting task. Beijing knows this and will continue to tighten and loosen the screws, as she deems appropriate.

Japan has a glass jaw, one that China could easily break if Japan does not act responsibly over the next few years. Japan is the only major nation in the world that has explicitly renounced war as a tool of policy. Article 9.1 of the Japanese constitution renounces war “as a sovereign right of the nation”. Article 9.2 asserts that “land, sea and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained”.

That said, Japan maintains very substantial “land, sea and air forces”. Japan’s military expenditures are, in fact, the third highest in the world. Tokyo has stockpiled over 100 tons of plutonium that would be relatively simple to transform into weapons’ grade material. Japan’s fast-breeder reactors (FBRs) have the capacity to squeeze over 60 times more energy from uranium fuel than can the light-water reactors of most other countries. Japan will, in other words, have the capacity to make more nuclear weapons than the combined arsenals of the United States and Russia hold. If nothing else, this arsenal makes an impressive bundle of bargaining chips.

Because its major challenges will come from the air, Japan has developed formidable anti-aircraft and anti-ballistic missile defense systems. Japan’s radar and its accurate Tomahawk missile technology far excel their American prototypes. Other Japanese strengths in miniaturization, automation, telecommunications and the development of durable, lightweight advanced materials further enhance their military capabilities.

Japan’s plutonium purchases have allowed it develop the necessary nuclear submarine technology to counter China’s blue water navy. Though impressive, a handful of nuclear submarines and a couple of batteries of missile defenses do not make Japan impregnable.

Bizarre as it seems, Japan’s expertise in these niche areas is a cause for concern in Washington. America fears lost market share if Japan exports its expertise – and, to develop the required expertise, Japan would have to copy the examples of Israel, Sweden, South Africa and other small countries and aggressively export. The United States fears that Japan would win export orders at its expense.

Japanese dual-use technological capabilities in commercial fields related to military use threatens the preeminent position American producers currently enjoy in the world’s arms’ markets. This is ironic as, historically, the United States encouraged Japan in its development of dual use capabilities. Spin-offs from the radio industry, for example, helped kick-start the Japanese commercial television industry, which eventually obliterated their American competitors.

Japan’s defense industry is, however, an inconsequential part of Japan’s overall industrial output. It accounts for less than 1 percent of Japanese gross domestic product (GDP) and even those firms, such as Mitsubishi Heavy Industries (MHI) and Kawasaki Heavy Industries (KHI), which are most heavily involved in it, are there mostly because of the spin-off technological benefits it has given them.

Whereas Japan has some particularly strong trees of knowledge, the forest overwhelmingly belongs to America. Japan just does not have the logistical depth of America or the European Union to be a major league player. While Japanese industry has established a global position in a wide range of critical modern technologies, Japan’s defense industry has lagged behind. At the systems level, military technology has simply moved faster than Japan’s ability to catch up.

Japan, in other words, does not have an autonomous arms industry. Today, the defense industry accounts for less than 0.6 percent of total industrial production, an almost insignificant amount in Japan’s overall context. Though Japan produces about 90 percent of its own military requirements, much of that is built under license from American firms and a considerable amount of the technology is black-boxed – sealed so that Japanese engineers cannot study and copy them.

In summary then, East Asia is in a state of chassis. Although Japan has neither the heart nor the materiel for what lies ahead, she, together with South Korea and Taiwan, must develop not only their autonomous defense systems but their own autonomous diplomatic voices as well. Japan’s future, whether she likes it or not, will be with its East Asian neighbors’ Belt and Road Initiative when the U.S. 7th Fleet, however belatedly, scuttles back to Pearl Harbor.