Ukraine has morphed – unexpectedly – from the Washington perspective from an ‘useful distraction’ to becoming Biden’s dilemma.

“What will we do if the West does not listen to reason?”, noted Sergei Lavrov. “Well, the President of Russia has already said ‘what’ [it will do]”. “If our attempts to come to terms on mutually acceptable principles of ensuring security in Europe fail to produce the desired result, we will take response measures. Asked directly what these measures might be, he [Putin] said: they could come in all shapes and sizes”. Russia had previously announced that absent a satisfactory western response, then Russia would lay aside the language of diplomacy – and resort to unspecified “military-technical” measures – incrementally ratchetting pain on NATO and the U.S.

It is unlikely that Moscow ever entertained any grand illusions about their ‘non-ultimatum’ ultimatum. The documents were never intended ‘to lure’ the West into ad aeternam negotiations. The point is that Moscow had already decided to break in a fundamental way with the West. What is afoot is today is the manifestation of that earlier decision.

The crux of Russia’s complaints about its eroding security have little to do with Ukraine per se but are rooted in the Washington hawks’ obsession with Russia, and their desire to cut Putin (and Russia) down to size – an aim which has been the hallmark of U.S. policy since the Yeltsin years. The Victoria Nuland clique could never accept Russia rising to become a significant power in Europe – possibly eclipsing the U.S.’ control over Europe.

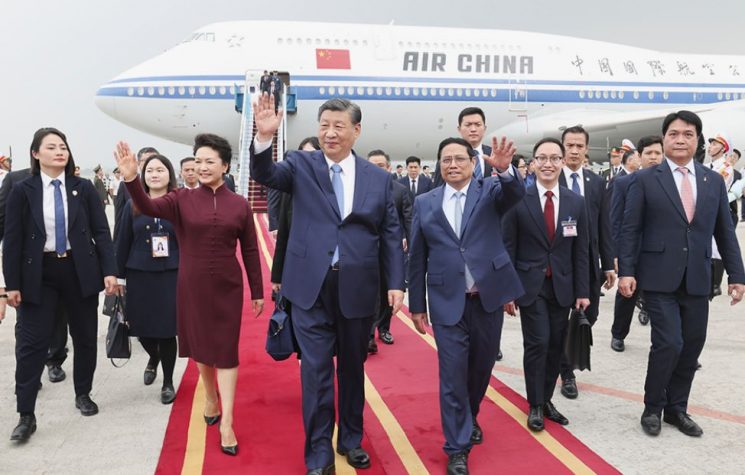

If they were not intended as a basis for negotiations, what then were Russia’s treaty drafts about? It seems that they were about Russia and China coming down off the fence. This is much more important than many appreciate. It marks the beginning of a period of rising tensions (and maybe clashes), until a modified Global Order emerges.

The ‘non-ultimatums’ primarily were intended to draw out, and make explicit in the public sphere, America’s refusal to concede the validity to Moscow’s point that its own security interests are of no lesser significance than those of Ukraine and Georgia; that one state’s security interests cannot be augmented at the expense of another (i.e. the indivisibility of security).

Making this clear to all is a necessary condition for a joint Russian-China shift to co-ordinated ‘military-technical measures’. It seems that shortly after Putin returns from his consultations with President Xi in China, we may begin to see what these military-technical measures might be. The Russian calculation is that in the run-up to the November ’22 midterms, the U.S. side will be increasingly nervous and internally vulnerable. Team Biden has no convincing rejoinder to the question asked by the electorate: ‘So, what is it that you guys got right this last year?” And so Biden badly needs a distraction from his inability to give an adequate reply.

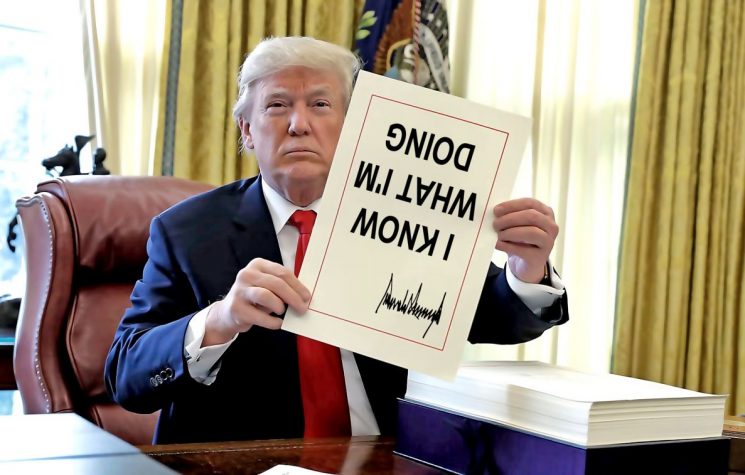

Ukraine has morphed – unexpectedly – from the Washington perspective from an ‘useful distraction’ to becoming Biden’s dilemma. Initially, a major info-war campaign on an unprecedented scale was thought to create a reason for Europe and America to impose ‘Sanctions from Hell’ that would put paid to Putin’s supposed ambitions in Europe, and beyond.

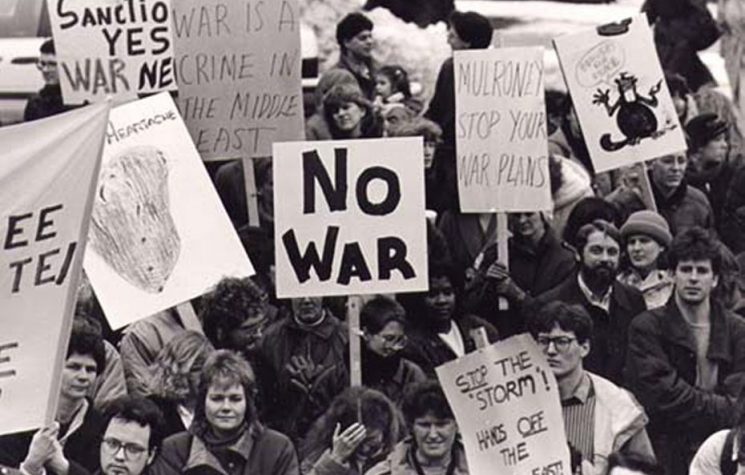

This apocalyptic sanctions ploy had its roots in the 2014 era, when the then Crimea sanctions (wrongly) were believed to be so utterly catastrophic for Russia that Putin’s future would be poised in the balance, bringing the possibility that he could be ousted by pro-western oligarchs. (Such was the mistaken analysis given to Angela Merkel by her own Intelligence Services).

It was so wrong: In 2014, Russia experienced only a mild recession (-2.2%), and in the event, its economy proved to be remarkably sanctions-proof, partly as a result of letting the Rouble ‘float’. This old meme of sanctions being the ‘neutron-bomb’ for Putin has been washed, rinsed and repeated by those (same old) Russia hawks – even though Russia’s economy is much more sanctions-proof today than it was in 2014. Thus the ‘Sanctions from Hell’ story has never held up; it is not credible.

The ‘imminent invasion’ frenzy perhaps, was thought by the hawks who seemed to have grabbed hold of the Washington ‘war narrative’, to be sufficient to goad Putin into military action – triggering these ‘Mother of all Sanctions’, or at the very least, a humiliating downsizing of the Russian forces adjacent to the Ukraine border:

Either outcome would easily have been presented as a ‘tough Biden’ successfully facing-down Putin and humiliating him. Earlier, U.S. think-tanks had rosily forecast that Putin was damned if he did; and damned if he didn’t take action over Ukraine. They were wrong. Essentially, Russia doesn’t want, or need Ukraine; there is no plan to occupy it.

It was firstly President Zelensky who unexpectedly did not co-operate with the U.S. plan. Instead of endorsing the threat of imminent Russian invasion, he claimed that invasion fears were overblown, and that the nervousness was bad for business, and the economy. Back at the time of the 2014 Maidan revolution, China had been promoting investment in Ukraine. Ditto today: Ukraine is reportedly on the brink of debt default, and has turned to China, looking for help.

This infuriated Washington: Julia Ioffe tweeted that the “White House and its Democratic allies have just about had it with President Zelensky. According to three sources in the administration and on the Hill, the Ukrainian president is by turns “annoying, infuriating, and downright counterproductive”. What is interesting is that these U.S. commentators’ principal moan was that Zelensky was not sufficiently attuned to domestic U.S. currents and narratives. There were rumours of a possible U.S.-led coup to replace Zelensky with a more compliant leader.

The invasion meme nonetheless is again being washed, rinsed and repeated: It continues life with a new allegation: this time that Russia is actively engaged in mounting a ‘false flag’ operation that would then justify a Russian invasion. This seemed so improbable that even normally compliant White House correspondents evinced utter disbelief.

And Washington’s problems just went on accumulating: the U.S.-orchestrated Security Council session was a débacle for Blinken: the ‘sanctions from hell’ have emerged as empty cymbals clashing, with fears taking hold that the sanctions would likely have hurt Europe more than hurt Russia; that they might even have provoked a global financial crisis. Reports suggest that the final nail was the Federal Reserve arguing that to expel Russia from SWIFT was a thoroughly bad idea.

And then, the second unexpected eruption for Blinken came: Europe (and NATO) far from being a resolute united front confronting Russia, clearly revealed their deep divisions.

Lavrov’s confirmation that the western responses to Moscow gave no basis for dialogue with the U.S. or NATO has an import which it seems has not been grasped. The crisis is not about Ukraine; as leading Russian journalist Dmitry Kiselyov noted: “The scale is much bigger”. It may, in the longer run, define Europe’s future as well as that of the Middle East.

It looks as if – even before the outcome of the Putin-Xi summit is known – Russia has already begun ‘coming down off the fence’, by which is meant, it is ready to dial up the pain for the U.S. and Europe slowly and deliberately on the basis that, if Russia’s concerns are ignored and dismissed, then Russia will ignore ‘yours’, too.

Russia clearly understands the geo-political and geo-economic pressure points that it controls. They can see that the U.S. does not want to raise interest rates, but has to. They can also see that they can force inflation far higher, inflicting significant economic pain. They can see that food prices are soaring, with potash from Belarus blocked, and Russia banning the export of ammonium nitrate.

The consequences for fertiliser prices – and therefore European food prices – is obvious, as is the consequence of European spot energy prices, were Russian gas to be barred from Europe. That is how economic pain works. The West slowly is discovering that that it has no pressure point versus Russia (its economy being relatively sanctions-proof), and its military is no match for that of Russia’s.

In the Middle East, a number of interesting developments have quietly taken place: Russia is mounting joint air-patrols with the Syrian Air Force over the Golan, and in the wake of Israel’s recent attacks on the port at Latakia, Russia has stationed its own forces there (meaning that Israel must stop attacking the port). Similarly, Israel recently complained to Russia that its’ blocking of the Global Positioning System (GPS) over Syria was adversely affecting Israeli commercial air traffic using Ben Gurion airport. The Russians replied, ‘Well, too bad’. And, in a forth blow to Israel, Russia has begun allowing Iranian planes carrying weapons supplies to land at the large Russian base in western Syria.

Is then, one military-technical action to block Israeli overflights of Syria? Might this also be a prelude to Russia enabling Damascus to regain control over the geographic extent of Syria – allowing the Syrian Arab Army to expel the jihadists from Idlib, and the Americans from north-east Syria, where they and their allies control Syria’s energy resources? The exodus of jihadis (some 2 million with dependents) would traumatise Turkish politics, damaging Erdogan’s re-election prospects, and terrify the Europeans with the threat of another migrant refugee crisis.

It looks like Russia has decided to come off the fence in other ways by inviting the new Iran president to Moscow and giving him full celebrity treatment: a one-to-one lunch with President Putin, plus a rare invitation to address the Russian Duma. This gesture, along with making Iran a full member of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), and the recent joint naval exercise with Iran, Russia and China in the Gulf of Oman, indicate Iran’s coming-of-age in international affairs.

Washington likes to compartmentalise its geo-political relations, believing it can be emollient in the ‘one’ compartment, but highly aggressive in an other. Clearly this no longer holds in the Russia-China axis. Iran however, is in a real way, a part of this Axis. Is it feasible now, to expect an Iranian JCPOA agreement with the U.S.? Can both Russia and China be saying – so explicitly – that the U.S. denial of any security sovereignty to either Russia or China marks the end to dialogue with the U.S., and yet expect that Iran would reach an accord precisely on such reductive terms?

Finally, what is the connection (if any), between the Houthis’ continuing attacks on the UAE, in response to the U.S. and Israel interfering directly in the Yemen war, and the Russian military-technical action project?

The port of Aden, the Bab al-Mandib Straits and Socotra Island fall neatly into a vital component of the Cold War build-up between China and the U.S. The Arab ally (in this case, the UAE) that can control this essential strait will give the U.S. leverage by which to jeopardize China’s Maritime Silk Road, and concomitantly, to weaken the East Asian Economic Community. Hence the key role of the Bab al Mandab Strait is seen by some Washington circles as the justification enough for America’s continued support for the war in Yemen.

The Houthis are giving the UAE a bitter choice: Strikes on its cities or yield up the strategic asset of Bab al-Mandab and its surrounds. Iran and China will be watching attentively. Is a new geo-strategic paradigm emerging?