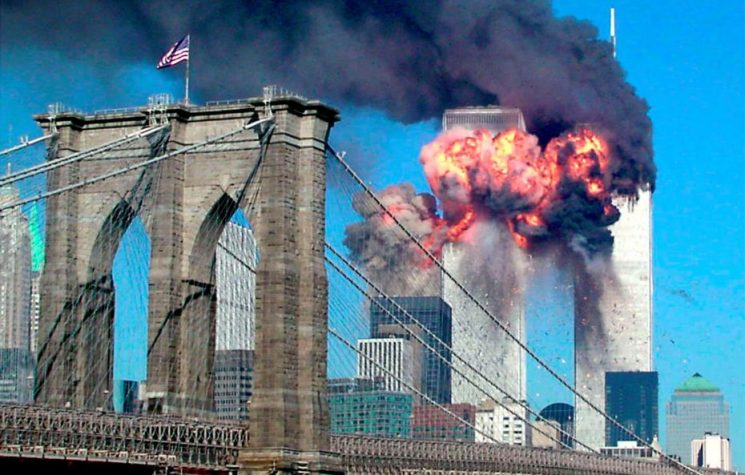

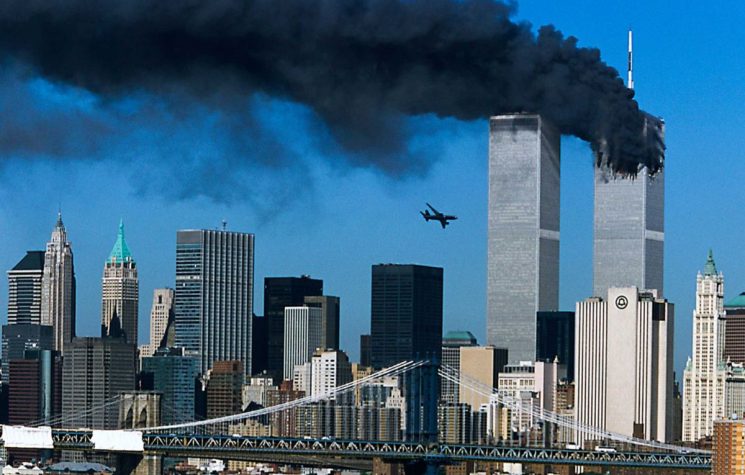

When Rumsfeld’s presence was needed more than ever before in his career, he went missing in action. What exactly was he doing on the morning of 9/11?

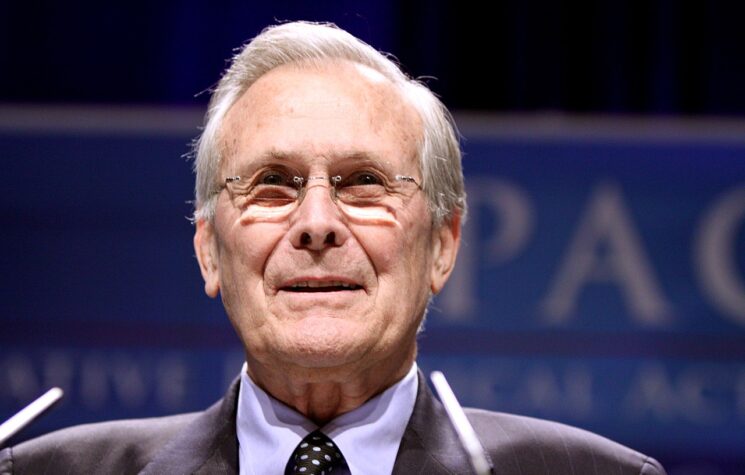

One question that many people ask with regards to the events of September 11 was why the U.S. Air Force went missing in action for over 90 minutes as four lumbering commercial jets traveled around American airspace at will. Now with the death of Donald Rumsfeld, 88, the world may never know.

Prior to the attacks of 9/11, a mosquito couldn’t penetrate U.S. airspace over Washington, D.C. without being intercepted or swatted down. So what went wrong that fateful Tuesday morning? For an answer to that question it is necessary to look at the actions and non-actions of then Secretary of Defense, Donald Rumsfeld, second in military command only behind President George W. Bush, who was out of the loop at the time, visiting a class of elementary school students down in Florida.

Rumsfeld, as Pentagon chief, was in charge of the National Military Command Center [NMCC], which was responsible for coordinating with the Federal Aviation Administration [FAA] in the event of a hijacking. But when Rumsfeld’s presence was needed more than ever before in his career, he went missing in action. So what exactly was Donald Rumsfeld doing on the morning of September 11?

According to the 9/11 Commission Report, around 9 a.m., just after American Airlines Flight 11 had slammed into the North Tower of the World Trade Center, “Secretary Rumsfeld was having breakfast at the Pentagon with a group of members of Congress. He then returned to his office for his daily intelligence briefing. The Secretary was informed of the second strike in New York [9:03 am] during the briefing; he resumed the briefing while awaiting more information.”

Various individuals pleaded with the Defense Secretary to cancel his morning appointments after news that a second plane had slammed into the World Trade Center. Yet Rumsfeld rejected their desperate appeals. The first person to meet with Rumsfeld after it was clear America was under attack was CIA agent, Denny Watson, who was responsible for giving Defense Secretary his intelligence briefing each morning. At 9:03 a.m., Watson was in the anteroom of Rumsfeld’s office where she witnessed the second plane hit the South Tower live on television. Moments later, she is called into the office and, clearly aware there are more pressing matters at hand, doesn’t bother to remove the President’s Daily Brief [PDB] from her briefcase. “Sir, you just need to cancel this,” she tells Rumsfeld upon entering the office, as cited in David Priess’s book, ‘The President’s Book of Secrets’. “You’ve got more important things to do.” Rumsfeld, however, insists on going ahead with the meeting. “No, no, we’re going to do this,” he tells her.

An incredulous Watson has a seat as the Secretary of Defense flips through the PDB.

Watson was not the only person who tried to impress upon Rumsfeld the urgency of the moment. Assistant Secretary of Defense for Public Affairs, Victoria Clarke, wrote in her 2006 book Lipstick on a Pig that she went directly to Rumsfeld’s office after the second plane hit. “A couple of us had gone into… Secretary Rumsfeld’s office, to alert him to that, tell him that the crisis management process was starting up. He wanted to make a few phone calls.” Rumsfeld reportedly told Clarke to report to the Executive Support Center (ESC) and wait for him. Clarke would wait a long time. Yet that was not the only emergency meeting Rumsfeld failed to attend on the morning of September 11.

The acting-Deputy Director of the National Military Command Center, Captain Charles Leidig, who was substituting for Brigadier General Montague Winfield on this very morning, called an emergency ‘significant event’ conference (SIEC). According to the Commission Report, the meeting “began at 9:29, with a brief recap: two aircraft had struck the World Trade Center…” Now if that summary failed to get Rumsfeld out of his office then clearly nothing would.

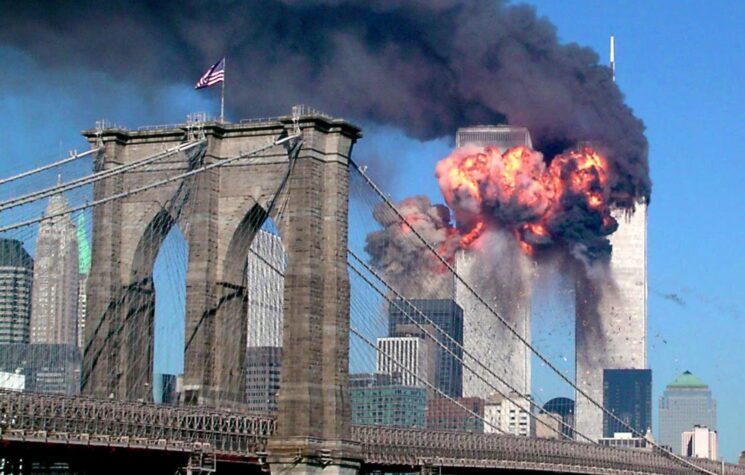

At 9:37 a.m., eight minutes after Captain Leidig had called the emergency response meeting, the Pentagon was rocked by what numerous witnesses said felt like a bomb detonating inside of the complex. The Commission Report briefly describes what action Rumsfeld took next: “After the Pentagon was struck, Secretary Rumsfeld went to the parking lot to assist with rescue efforts.” Now just try and rationalize that decision.

Rumsfeld, the highest ranking commander of the U.S. military aside from the President of the United States, has taken it upon himself to inspect the crash site and assist with the search and rescue efforts. A quaint, touching story that the media happily devoured, and the Commission Report completely ignored, but an altogether implausible one. That is not to deny the claim, however, that Rumsfeld was on the front lawn of the Pentagon assisting with the rescue efforts. Indeed, there are photographs showing the Defense Secretary, with a security detail at his side, doing exactly that.

Paul Wolfowitz, in an interview with Vanity Fair, spoke glowingly about how his boss responded to the emergency: “He went charging out and down to the site where the plane had hit, which is what I would have done if I’d had my wits about me, which may or may not have been a smart thing to do, but it was. Instead, the next thing we heard was that there’d been a bomb and the building had to be evacuated. Everyone started streaming out of the building in a quite orderly way.”

So Wolfowitz is somehow of the opinion that Rumsfeld abandoning his command post and dashing outside to the Pentagon blast site, where more attacks could have been forthcoming, was the best course of action. The media papering over Rumsfeld’s disastrous actions did not stop there.

In the New York Times, journalist Andrew Cockburn provided a breathless account of Rumsfeld, the military man of impetuous action, as he inexplicably traversed about two miles around the Pentagon – each side of the Pentagon complex is around the length of three football fields – to inspect the damage site and help the wounded instead of leading the nation at its most critical hour. Brace yourself because this is classic.

“There were the flames, and bits of metal all around,” Cockburn writes, quoting Officer Aubrey Davis of the Pentagon police, who served as Rumsfeld’s personal bodyguard during this mindless morning jog. “The secretary picked up one of the pieces of metal. I was telling him he shouldn’t be interfering with a crime scene when he looked at some inscription on it and said, ‘American Airlines.’ Then someone shouted, ‘Help, over here,’ and we ran over and helped push an injured person on a gurney over to the road.”

Cockburn proceeds to pin media laurels on Rumsfeld’s chest when what the Pentagon chief really deserved was a military tribunal: “[T]hose few minutes made Rumsfeld famous, changed him from a half-forgotten twentieth-century political figure to America’s twenty-first-century warlord. On a day when the president was intermittently visible, only Rumsfeld, along with New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani, gave the country an image of decisive, courageous leadership… Over time, the legend grew. One of the staffers in the office later assured me that Rumsfeld torn his shirt into strips to make bandages for the wounded …”

Keep in mind, Rumsfeld was paid to serve as chief of the military, not as a nurse.

Rumsfeld returned to the Pentagon building by 10 o’clock and despite desperate pleas from staff members, he continued to avoid the command center as if it were a leper colony. Instead, he went back to his office where he had a phone conversation with President Bush, though, as Cockburn reported, “neither man could recall what they discussed.”

Rumsfeld did not make it to the command center until 10:30 a.m., which, by that time, was too late to do anything of consequence, except to have a phone conversation with Dick Cheney, who was holed up in the basement of the White House.

As the authors of the Commission Report noted, “Secretary Rumsfeld told us he was just gaining situational awareness when he spoke with the Vice President at 10:39. His primary concern was ensuring that the pilots had a clear understanding of their rules of engagement.” Well, that concern arose about two hours too late. Rumsfeld’s presence at this point was no longer even symbolic. The emergency, for all intent and purposes, was already over. Now it was up to the media to twist this unforgivable dereliction of duty into some sort of act of heroism. And it was only too happy to comply.