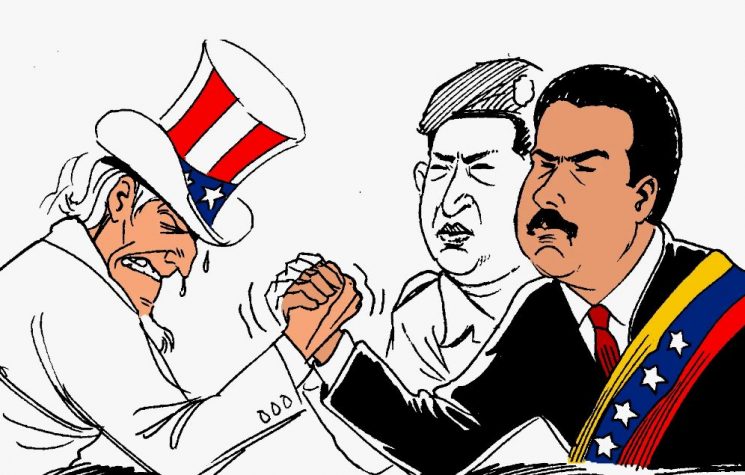

It will be fascinating to watch how the (Dis)United States will deal with post-coup Myanmar as part of their 24/7 “containment of China” frenzy.

The (jade) elephant in the elaborate room housing the military coup in Myanmar had to be – what else – China. And the Tatmadaw – the Myanmar Armed Forces – knows it better than anyone.

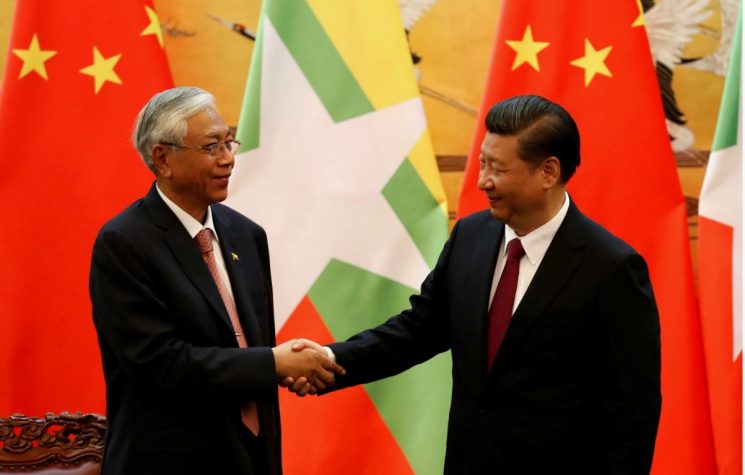

There’s no smoking gun, of course, but it’s virtually impossible that Beijing had not been at least informed, or “consulted”, by the Tatmadaw on the new dispensation.

China, Myanmar’s top trade partner, is guided by three crucial strategic imperatives in the relationship with its southern neighbor: trade/connectivity via a Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) corridor; full access to energy and minerals; and the necessity of cultivating a key ally within the 10-member ASEAN.

The BRI corridor between Kunming, in China’s Yunnan province, via Mandalay, to the port of Kyaukphyu in the Gulf of Bengal is the jewel in the New Silk Road crown, because it combines China’s strategic access to the Indian Ocean, bypassing the Strait of Malacca, with secured energy flows via a combined oil and gas pipeline. This corridor clearly shows the centrality of Pipelineistan in the evolution of the New Silk Roads.

None of that will change, whoever runs the politico-economic show in Myanmar’s capital Naypyidaw. Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi and Aung San Suu Kyi, locally known as Amay Suu (“Mother Suu”) were discussing the China-Myanmar economic corridor only three weeks before the coup. Beijing and Naypyidaw have clinched no less than 33 economic deals only in 2020.

We just want “eternal peace”

Something quite extraordinary happened earlier this week in Bangkok. A cross-section of the vast Myanmar diaspora in Thailand – which had been ballooning since the 1990s – met in front of the UN’s Asia-Pacific office.

They were asking for the international reaction to the coup to ignore the inevitable, incoming U.S. sanctions. Their argument: sanctions paralyze the work of citizen entrepreneurs, while keeping in place a patronage system that favors the Tatmadaw and deepens the influence of Beijing at the highest levels.

Yet this is not all about China. The Tatmadaw coup is an eminently domestic affair – which involved resorting to the same old school, CIA-style method that installed them as a harsh military dictatorship way back in 1962.

Elections this past November reconfirmed Aung San Suu Kyi and her party, the NLD, in power by 83% of the votes. The pro-army party, the USDP, cried foul, blaming massive electoral fraud and insisting on a recount, which was refused by Parliament.

So the Tatmadaw invoked article 147 of the constitution, which authorizes a military takeover in case of a confirmed threat to sovereignty and national solidarity, or capable of “disintegrating the Union”.

The 2008 constitution was drawn by – who else – the Tatmadaw. They control the crucial Interior, Defense and Border ministries, as well as 25% of the seats in Parliament, which allows them veto power on any constitutional changes.

The military takeover involves the Executive, the Legislative and the Judiciary. A year long state of emergency is in effect. New elections will happen when order and “eternal peace” will be restored.

The man in charge is Army chief Min Aung Hlaing, quite flush after years overseeing juicy deals conducted by Myanmar Economic Holdings Ltd. (MEHL). He also oversaw the hardcore response to the 2007 Saffron revolution – which did express legitimate grievances but was also largely co-opted as a by-the-book U.S. color revolution.

More worryingly, Min Aung Hlaing also deployed wasteland tactics against the Karen and Rohingya ethnic groups. He notoriously described the Rohingya operation as “the unfinished work of the Bengali problem”. Muslims in Myanmar are routinely debased by members of the Bamar ethnic majority as “Bengali”.

No raised ASEAN eyebrows

Life for the overwhelming majority of the Myanmar diaspora in Thailand can be very harsh. Roughly half dwell in the construction business, the textile industry and tourism. The other half does not hold a valid work permit – and lives in perpetual fear.

To complicate matters, late last year the de facto military government in Thailand went on a culpability overdrive, blaming them for crossing borders without undertaking quarantine and thus causing a second wave of Covid-19.

Thai unions, correctly, pointed to the real culprits: smuggling networks protected by the Thai military, which bypass the extremely complicated process of legalizing migrant workers while shielding employers who infringe labor laws.

In parallel, part of the – legalized – Myanmar diaspora is being enticed to join the so-called MilkTeaAlliance – which congregates Thais, Taiwanese and Hong Kongers, and lately Laotians and Filipinos as well – against, who else, China, and to a lesser extent, the Thai military government.

ASEAN won’t raise eyebrows against the Tatmadaw. ASEAN’s official policy remains non-interference in the domestic affairs of its 10 members. Bangkok – where, incidentally, the military junta took power in 2014 – has shown Olympic detachment.

In 2021, Myanmar happens to be coordinating nothing less than the China-ASEAN dialogue mechanism, as well as presiding over the Lancang-Mekong Cooperation – which discusses all crucial Mekong matters.

The mighty river, from the Tibetan plateau to the South China Sea, could not be more geo-economically strategic. China is severely criticized for the building of dozens of dams, which reduce direct water flows and cause serious imbalances to regional economies.

Myanmar is also coordinating a supremely sensitive geopolitical issue: the interminable negotiations to establish the Code of Conduct in the South China Sea, which pit China against Vietnam, Malaysia, Philippines, Indonesia, Brunei and non-ASEAN Taiwan.

The Tatmadaw does not seem to be losing sleep over post-coup business problems. Erik Prince, former Blackwater honcho and now the head of Hong Kong-based Frontier Services Group (FSG) – financed, among others, by powerful Chinese conglomerate Citic – is about to hit Naypyidaw to “securitize” local companies.

A juicier dossier involves what’s going to happen with the drug trade: arguably Tatmadaw getting a bigger piece of the pie. Cartels in Kachin state, in the north, export opium to China’s Yunnan province to the east, and India to the west. Shan state cartels are even more sophisticated: they export via Yunnan to Laos and Vietnam to the east, and also to India to the northwest.

And then there’s a gray area where no one really knows what’s going on: the weapons highway between China and India that runs through Kachin state – where we also find Lisu and Lahu ethnic groups.

The dizzying ethnic tapestry

The Myanmar electoral commission is a very tricky business, to say the least. They are designated by the Executive, and had to face a lot of criticism – internal, not international – for their censorship of opposition parties in the November elections.

The end result privileged the NLD, whose support is negligible in all border regions. Myanmar’s majority ethnic group – and the NLD’s electoral base – is the Bamar, Buddhist and concentrated in the central part of the country.

The NLD frankly does not care about the 135 ethnic minorities – which represent at least one third of the general population. It’s been a long way down since Suu Kyi came to power, when the NLD actually enjoyed a lot of support. Suu Kyi’s international high profile is essentially due to the power of the Clinton machine.

If you talk to a Mon or a Karen, he or she will tell you they had to learn the hard way how much of an intolerant autocrat is the real Suu Kyi. She promised there would be peace in the border regions – eternally mired in a fight between the Tatmadaw and autonomous movements. She could not possibly deliver because she had no power whatsoever over the military.

Without any consultation, the electoral commission decided to cancel voting, totally or partially, in 56 cantons of Arakan state, Shan state, Karen state, Mon state and Kachin state, all of them ethnic minorities. Nearly 1.5 million people were deprived of voting.

There were no elections, for instance, in the majority of Arakan state; the electoral commission invoked “security reasons”. The reality is the Tatmadaw is in a bitter fight against the Arakan Army, which want self-determination.

Needless to add, the Rohingyas – which live in Arakan – were not allowed to vote. Nearly 600,000 of them still barely survive in camps and closed villages in Arakan.

In the 1990s, I visited Shan state, which borders China’s strategic Yunnan province to the east. Nothing much changed over two decades: the guerrilla has to fight the Tatmadaw because they clearly see how the army and their business cronies are obsessed to capture the region’s lavish natural resources.

I traveled extensively in Myanmar in the second part of the 1990s – before being blacklisted by the military junta, like virtually every journalist and analyst working in Southeast Asia. Ten years ago, photojournalist Jason Florio, with whom I’ve been everywhere from Afghanistan to Cambodia, managed to be sneaked into Karen rebel territory, where he shot some outstanding pictures.

In Kachin state, rival parties in the 2015 elections this time tried to pool their efforts. But in the end they were badly bruised: the electoral mechanism – one round only – favored the winning party, Suu Kyi’s NLD.

Beijing does not interfere in the dizzyingly complex Myanmar ethnic maze. But questions remain over the murky support for Chinese who live in Kachin state in northern Myanmar: it’s possible they may be used as leverage in negotiations with the Tatmadaw.

The basic fact is the guerrillas won’t go away. The top two are the Kachin Independence Army and the United Wa State Army (Shan). But then there’s the Arakan Liberation Army, the China National Army, the Karenni Army (Kayah), the Karen National Defense Organization and the Karen National Liberation, and the Mon National Liberation Army.

What this weaponized tapestry boils down to, in the long run, is a tremendously (Dis)United Myanmar, bolstering the Tatmadaw’s claim that no other mechanism is capable of guaranteeing unity. It doesn’t hurt that “unity” comes with the extra perks of controlling crucial sectors such as minerals, finance and telecom.

It will be fascinating to watch how the (Dis)United Imperial States will deal with post-coup Myanmar as part of their 24/7 “containment of China” frenzy. The Tatmadaw are not exactly trembling in their boots.