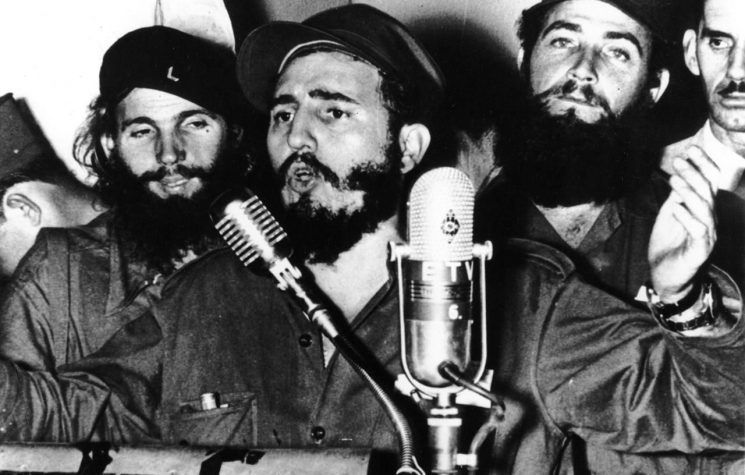

This September marked 60 years since Fidel Castro’s first address to the United Nations, in which he delivered a scathing and truthful critique about the imperialist philosophy of war. On September 26, 1960, facing the beginning of U.S. political hostilities against Cuba, while the Cuban delegation to the UN was excluded from meetings and diplomatic events, Fidel’s speech, lasting over five hours, was an eloquent reflection that seamlessly weaved the implications of U.S. supremacy in a historical narrative from the colonised country’s experience and perspective.

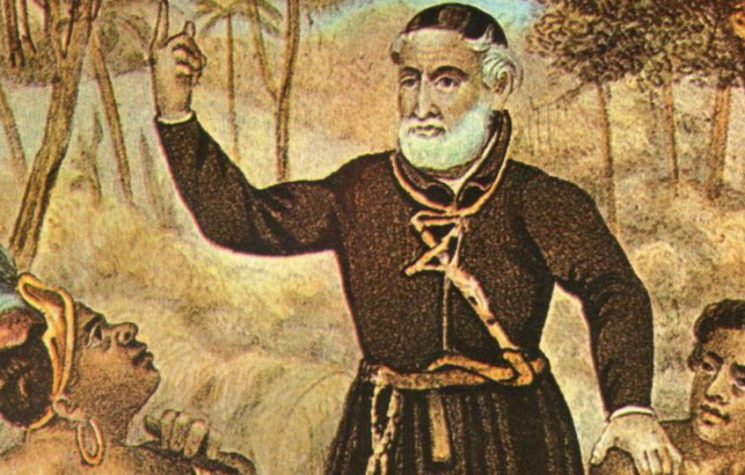

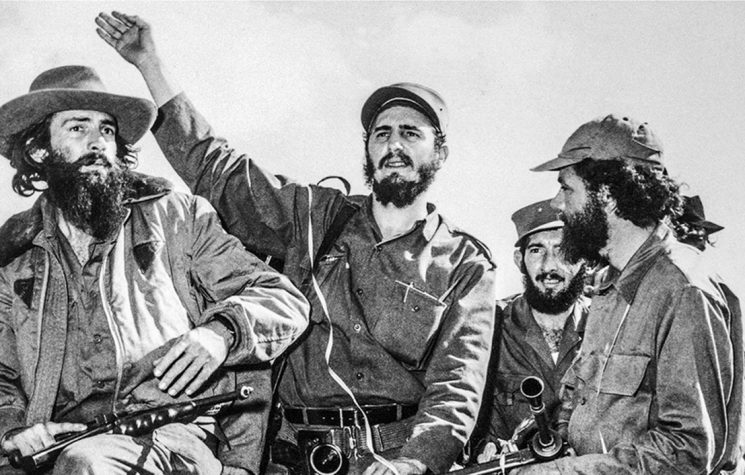

“Colonies do not speak. Colonies are not known until they have the opportunity to express themselves. That is why our colony and its problems were unknown to the rest of the world,” Fidel asserted. The Cuban struggle for independence was perceived as an opportunity for the U.S. to intervene and exploit the island, through a clause included in the Cuban constitution in 1901 which ensured U.S. dominance. Before the Cuban Revolution, the country had merely transitioned from a Spanish colony to a U.S. colony. The latter’s expectations were of a failed revolution, but Fidel’s strategy involved both revolutionary consciousness and mobilisation.

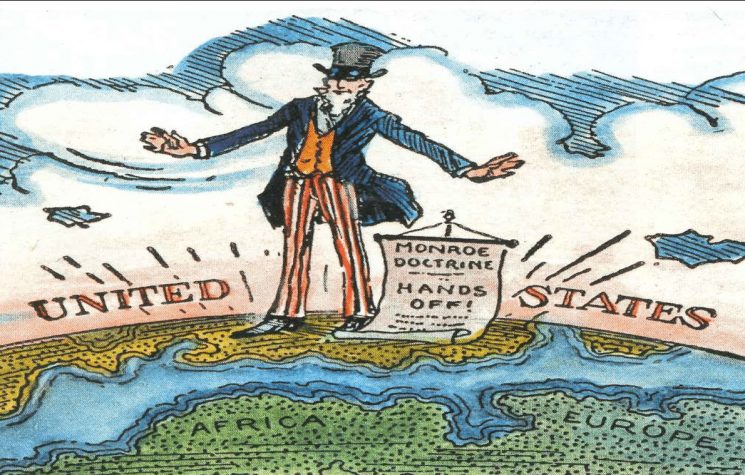

Within the context of Latin American history, Fidel’s UN speech exposed the monopoly of U.S.-backed dictators in the region and how these were also exploited in turn once the U.S. determined that backing them would no longer suit imperialist interests. The regional experience was an important comparison, for Cuba’s social inequalities as a result of Fulgencio Batista’s dictatorship were a common experience throughout Latin America.

During his speech, Fidel exhibited a document – a military pact – in which Batista’s government and the U.S. had agreed upon “efficient use of assistance” to prevent the advancing of the Cuban Revolution. Protecting Batista’s government also translated to protecting U.S. interests in the country; the pacts were described by Fidel as “defence pacts for the protection of United States monopolies.”

Perhaps most explicitly, Fidel’s detailed descriptions of Cuba’s challenges, including agrarian reform, provided Latin American governments with insights as to how imperialism exploited colonised territory, including the wilful U.S. destruction of Cuba’s sugar cane fields during harvest time, in a bid to sabotage Cuba’s economy under revolutionary governance. Latin American dependence upon the U.S., after all, was what allowed imperialism to retain a foothold in the region. An economy which failed to prosper would provide the U.S. with the chance to recolonise Cuba – a chance that Fidel was not allowing and which was thwarted through the revolution’s insistence upon education and revolutionary participation in rebuilding Cuba.

One important point made in Fidel’s speech is the acknowledgement that Cuba was not alone in facing such aggression, thus communicating the Cuban revolution’s region and international approach. Another façade of U.S. interference in the region was the sudden U.S. proposals for social development, at a time when the Cuban Revolution had mobilised its citizens and within its means to rebuild the country’s social structure. These interventions were later effected in the region through USAID, planned during the presidency of Dwight Eisenhower and carried out by J F Kennedy. To put it briefly, the U.S. intended humanitarian intervention as a veneer to maintain control over Cuba and Latin America through purported social and economic development and incentives. Subsequently, this paradigm was expanded to legitimise the Cuban counter-revolutionary activities as purported “forces in exile that are struggling for freedom”, in complete dissociation from the fact that these dissident groups worked closely with the CIA and were funded by the U.S. government.

In contrast to the U.S., the Cuban Revolution expressed a staunch position against war and exploitation. Had the UN not been monopolised by the greater political powers, Fidel’s speech could have been a turning point in international history. Without resorting to useless resolutions, as is the UN’s alternative to political solutions, Cuba’s revolutionary philosophy was succinctly outlined by Fidel: “Do away with the philosophy of plunder and you will have done away forever with the philosophy of war.”