In January 2018 I advanced the hypothesis that U.S. President Trump understood that the only way to “Make American Great Again” was to disentangle it from the imperial mission that had it stuck in perpetual wars. I suggested that the cutting of this “Gordian Knot of entanglements” was difficult, even impossible, to accomplish from his end and that he understood that the cutting could only come from the other side. I followed up with another look the next March. I now look at my hypothesis as Trump’s first term comes to an end.

While we are no closer to knowing whether this is indeed Trump’s strategy or an unintended consequence of his behaviour, it is clear that the “Gordian knot of U.S. imperial entanglements” is under great strain.

German-American relations provide an observation point. There are four demands the Trump Administration makes of its allies – Huawei, Iran, Nord Stream 2 and defence spending – and all four converge on Germany. Germany is one of the most important American allies; it is probably the second-most important NATO member; it is the economic engine of the European Union. Should it truly defy Washington on these issues, there would be fundamental damage to the U.S. imperium. (And, if George Friedman is correct in stating that preventing a Germany-Russia coalition is the “primordial interest” of the USA, the damage could be greater still.) And yet that is what we are looking at: on several issues Berlin is defying Washington.

Washington is determined to knock Huawei, the Chinese telecommunications company, out of the running for 5G networks even though, by most accounts, it is the clear technological leader. In March Berlin was told that Washington “wouldn’t be able to keep intelligence and other information sharing at their current level” if Chinese companies participated in the country’s 5G network. As of now, Berlin has not decided one way or the other (September is apparently the decision point). London, on the other hand, which had agreed to let Huawei in, reversed its decision, it is reported, when Trump threatened to cut intelligence and trade. So one can imagine what pressures are being brought on Berlin.

Berlin was very involved in negotiating the nuclear agreement with Tehran – the JCPOA – and was rather stunned when Washington pulled out of it. German Chancellor Merkel acknowledged that there wasn’t much Europe could do about it: but added that it “must strengthen them [its capabilities] for the future“. When Washington forced the SWIFT system to disconnect from Iran, thereby blocking bank-to-bank transactions, Berlin, Paris and London devised an alternate system called INSTEX. But, despite big intentions, it has apparently been used only once – in a small medical supplies transaction in March.

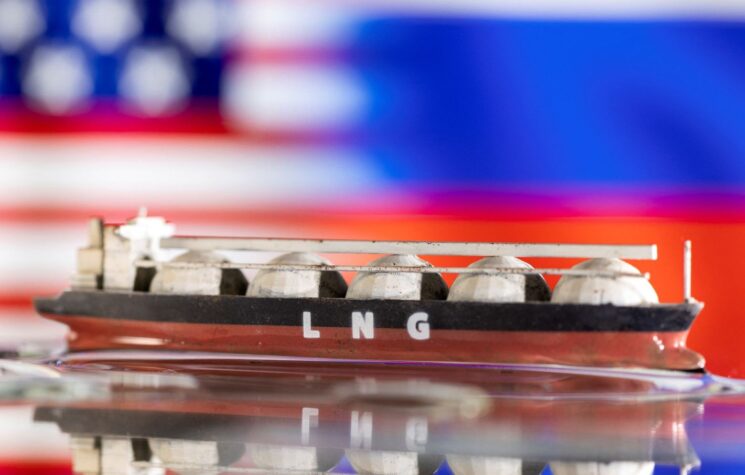

Thus far, Berlin’s resistance to Washington’s diktats has not amounted to much but on the third case it has been defiant from the start. Germany has been buying hydrocarbons from the east for some time and it is significant that, throughout the Cold War, when the USSR and Germany were enemies, the supply never faltered. And the reason is not hard to understand: Berlin wants the energy and Moscow wants the money; it’s a mutual dependence. The dependence can be exaggerated: a BBC piece calculated two years ago that Germany got about 60% of its gas from Russia but that only about 20% of Germany’s energy came from gas: a total of 12%. But it is very likely that that 12% will grow in the future and Russian supply will become more important to Germany. On the other hand, while it is happy to get the business, given the limitless demand from China, Russia could give up the European market if it had to. But, at present, it remains a mutually beneficial trade.

Given the problems of gas transit through Ukraine, the Nord Stream pipeline under the Baltic was built and began operation in 2011. As demand and the unreliability of Ukrainian politics grew, a second undersea pipeline, Nord Stream 2, began to be constructed. It was nearing completion when Washington imposed sanctions and the Swiss company that was laying the pipe quit the job. A Russian pipe-laying ship appeared and the work continues. Meanwhile Washington redoubles its efforts to force a stop. Ostensibly Washington argues security concerns – making the not-unreasonable argument that while Germany talks about the “Russian threat” it nevertheless buys energy from Russia: which is it? dangerous or reliable? Many people, on the other hand, believe that the true motive is to compel Germany to buy LNG from the USA; or “freedom gas” as they like to call it. This passage deserves to be pondered

LNG is significantly more expensive than pipeline gas from Russia and Norway, which are currently the two main exporters of gas to Europe. But some EU countries – chiefly Poland and the Baltic states – are ready to pay a premium in order to diversify their supplies. Bulgaria, which is currently 100% reliant on Russian gas, said it was ready to import LNG from the U.S. if the price was competitive, suggesting a $1 billion U.S. fund could be used to bring the price down. But Perry dismissed any suggestion that the U.S. government would interfere on pricing, saying it was up to the companies involved to sign export and import deals.

Freedom isn’t free, as they say.

In July the U.S. Congress added to the military funding bill an amendment expanding sanctions in connection with Nord Stream 2 to include any entity that assists the completion of the pipeline. Which brings us to the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act. This extremely open-ended bill arrogates to Washington the right to 1) declare this or that country an “adversary” 2) sanction anyone or anything that deals with it, or deals with those who deal with it and so on. Eventually, virtually every entity on the planet could be subject to sanctions (except, of course, the USA itself which permits itself to buy rocket engines or oil from “adversary” Russia). In short, if you don’t freely choose to buy our “freedom gas”, we’ll force you to. The latest from U.S. Secretary of State Pompeo is: “We will do everything we can to make sure that that pipeline doesn’t threaten Europe” (the pretext of security again). Berlin has re-stated its determination to continue with it. 24 EU countries have issued a démarche to Washington protesting this attempt at extraterritorial sanctions. The convenient “poisoning” of Navalniy is being boomed as reason for Berlin to obey Washington’s diktat. This far Merkel says the two should not be linked. But the pressure will only grow.

Another of Trump’s oft-stated themes is that the U.S. is paying to defend countries that are rich enough to defend themselves. NATO agreed some years ago that its members should commit 2% of governmental spending to defence. Few have achieved this and Germany least of all – 2019’s spending was about 1.2%; the undertaking to raise it to 1.5% by 2024 will probably not be fulfilled. Presumably as a consequence, or because he imagines he’s punishing Germany for its contumacy, Trump has ordered 12,000 troops to be removed from Germany. It is significant that most Germans are pretty comfortable with that reduction; about a quarter want them all gone. Which suggests that Germans are not as enthusiastic about their connection with the USA as their governments have been and so one may speculate that a post-Merkel Chancellor might be prepared to act on this indifference and cut the ties.

Iran is on Washington’s “adversary list” and Washington is determined to break it. Having walked out of the JCPOA, Washington is now trying to get the other signatories to impose sanctions on it for allegedly breaking the deal. This ukase is proving to be another point of disagreement and Paris, London and Berlin have refused to join in this effort stating that they remain committed to the agreement; in Pompeo’s chiaroscuric universe this was “aligning themselves with the Ayatollahs“. This failure followed another at the UNSC a week earlier. Again, the knot is not severed but it is weakened as the U.S. Secretary of State comes ever closer to accusing Washington’s principal allies of being “adversaries” and they refuse obedience.

And so we can see that the Trump Administration is stamping around the room, smashing the furniture, brusquely ordering its allies to do as they’re told or else. One could hardly find a better exponent of this in-your-face style than “we lied, we cheated, we stole” Mike Pompeo. If your object were to outrage allies so much that they quit themselves, he’s ideal. Washington’s demands, stripped of the highfalutin accompanying rhetoric of freedom, are: join its sanctions against China and Iran; buy its gas; buy its weapons; if not, risk being declared “adversaries” in a sanctions war. Germany is defiant on Huawei, Iran, Nord Stream and weaponry; much of Europe is as well and Berlin’s example will have much effect on the others.

Point-blank demands to instantly fall in with Washington’s latest scheme is certainly no way to treat allies. But is this part of a clever strategy to get them to cut the “Gordian Knot of entanglements” themselves or just America-firstism stripped of politesse? Some see an intention here:

Even The Economist, that reliable indicator of the mean sea level of conventional opinion, wonders:

But it is only under President Donald Trump that America has used its powers routinely and to their full extent, by engaging in financial warfare. The results have been awe-inspiring and shocking. They have in turn prompted other countries to seek to break free of American financial hegemony.

A year ago French President Macron said Europe could no longer count on American defence. German Chancellor Merkel at first disagreed, but as Berlin’s struggles with Washington intensify, now sounds closer to Macron’s position. Just words to be sure, but evolving words.

If Trump gets a second term (the better bet at this moment, I believe) these words may become actions. At least one calculation assesses that the sanction wars have cost the EU more than Russia and very much more than the USA which has carefully exempted itself. Many Europeans must be coming to appreciate that there is more cost than gain in the relationship. (Which, of course, explains the rolling sequence of anti-Russian and anti-Chinese stories calculated to frighten them back into line.) As the slang phrase has it, the Trump Administration is saying “my way or the highway”. The Europeans are certainly big enough to set off on the highway by themselves.