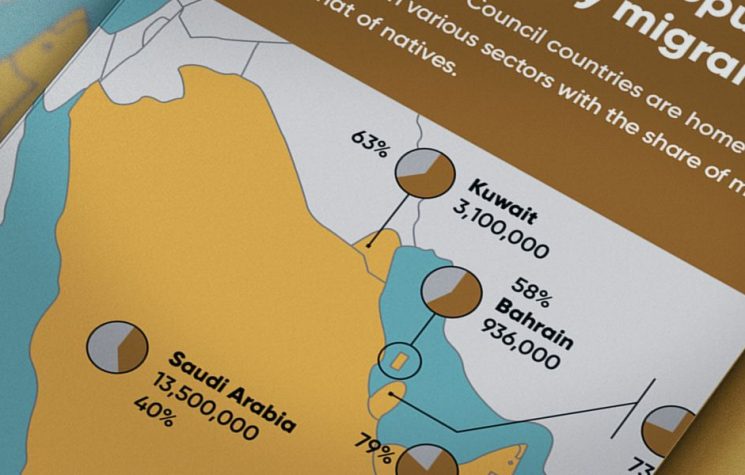

As commentators focus on the hospitalisations of two Gulf monarchs, and permutate likely succession issues, they may miss the wood for the succession trees: Of course, the death of either the Emir of Kuwait (91 years old) or King Salman of Saudi Arabia (84 years old) is a serious political matter. King Salman’s particularly has the potential to upturn the region (or not). Yet Gulf stability today rests less on who succeeds, but rather on tectonic shifts in geo-finance and politics that are just becoming visible. Time to move on from stale ruminations about who’s ‘up and coming’, and who’s ‘down and out’ in these dysfunctional families.

The stark fact is that Gulf stability rests on selling enough energy to buy-off internal discontents, and to pay for supersized surveillance and security set-ups.

For the moment, times are hard, but the States’ financial ‘cushions’ are just about holding-up (albeit only for the big three: Saudi Arabia, Abu Dhabi and Qatar). For others the situation is dire. The question is, will this present status quo persist? This is where the warnings of shifts in certain global tectonic plates becomes salient.

The Kuwaiti succession struggle is emblematic of the Gulf rift: One candidate for Emir, (the brother), stands with Saudi Arabia and its Wahhabi-led ‘war’ on Sunni Islamists (the Muslim Brotherhood). Whereas the other, (the eldest son), is actively backed by the Muslim Brotherhood, Qatar and Turkey. Thus, Kuwait sits on firmly on the Gulf abyss – a region with significant, but disempowered Shi’a minorities, and a Sunni camp divided and ‘at war’ with itself over support for the Muslim Brotherhood; or what is (politely called) ‘autocratic secular stability’.

Interesting though this is, is this really still so relevant?

The Gulf, perhaps more significantly, is held hostage to two huge financial bubbles. The real risk to these States may prove to come from these bubbles, which are the very devil to prick-down into any gentle, expelling of gas. They are sustained by mass psychology – which can pivot on a dime – and usually end catastrophically in a market ‘tantrum’, or a ‘bust’ – and with consequent risk of depression, should Central Banks ever try to lift the foot off the monetary accelerator.

The U.S. ubiquitous ‘asset bubble’ is famous. Central Bankers have been worrying about it for years. And the Fed is throwing money at it – with abandon – to keep it from popping. But as indicated earlier, such bubbles are highly vulnerable to psychology – and that may be turning, as the celebrated V-shaped, expected economic recovery recedes into the virus-induced distance. But for now, investors believe that the Fed daren’t let it implode – that the Fed has absolutely no option but go on throwing more and more money at it (at least until November elections … & then what?).

Less visible is that other vast ‘asset bubble’: The Chinese domestic property market. With its closed capital account, China has a huge sum (some $40 trillion) sloshing around in collective bank accounts. That money can’t go abroad (at least legally), so it rotates around between three asset markets: apartments, stocks, and commodities somewhat whimsically. But investing in apartments is absolutely king! 96% of urban Chinese own more than one: 75% of private wealth is represented by investments in condos – albeit with 21% standing empty in urban China, for lack of a tenant.

Long story, short, the Chinese massively chase property valuations. Indeed, as the WSJ has noted “the central problem in China is that buyers have figured out the government doesn’t appear to be willing to let the market fall. If home prices did drop significantly, it would wipe out most citizens’ primary source of wealth, and potentially trigger unrest”. Even during the pandemic – or, perhaps because of it as the Chinese piled-in – prices rose 4.9% in June, year on year. The total value of Chinese homes and developers’ inventory hit $52 trillion in 2019, according to Goldman Sachs; i.e. twice the size of the U.S. residential market, and outstripping even the entire U.S. bond market.

If it sounds just like America’s QE-inflated asset markets, that’s because it is. As things stand, both the Chinese residential and the U.S. equity bubbles are unstable. Which might fracture fist? Who knows … but bubbles are also vulnerable to pop on geo-political events (such as a U.S. naval landing on one of China’s disputed South Sea islands, to which China is promising, absolutely, a military response).

No one has any idea how Chinese officials can manage the property bubble, without destabilizing the broader economy. And even should the market stay strong, it creates headaches for policy makers, who have had to hold off on more aggressive economic stimulus this year – which some analysts say is needed, partly because of fears it will inflate housing further.

Ah … there it is: Out in plain view – the risk. The condo-trade has hijacked the entire Chinese economy, tying officials’ hands. This, at the moment when Trump’s trade war has turned into a new ideological cold war targeting the Chinese Communist Party. What if the Chinese economy, under further U.S. sanctions, slides further, or if Covid 19 resurges (as it is in Hong Kong)? Will then the housing market break, causing recession or depression? It is, after all, China and Asia that buy the bulk of Gulf energy: Demand shrinks, and price falls. The fate of the Gulf States’ economies – and stability – is tied to these mega-bubbles not popping.

Bubbles are one factor, but there are also signs of the tectonic plates drifting apart in a different way, but no less threatening. Bankers Goldman Sachs sits at the very heart of the western financial system – and incidentally staffs much of Team Trump, as well as the Federal Reserve.

And Goldman wrote something this week that one might not expect from such a system stalwart: Its commodity strategist Jeffrey Currie, wrote that “real concerns around the longevity of the U.S. dollar as a reserve currency have started to emerge”.

What? Goldman says the dollar might lose its reserve currency status. Unthinkable? Well that would be the standard view. Dollar hegemony and sanctions have long been seen as Washington’s stranglehold on the world through which to preserve U.S. primacy. America’s ‘hidden war’, as it were. Trump clearly views the dollar as the bludgeon that can make America Great Again. Furthermore, as Trump and Mnuchin – and now Congress – have taken control of the Treasury arsenal, the roll-out of new sanctions bludgeoning has turned into a deluge.

But there has also been within certain U.S. circles, a contrarian view. Which is that the U.S. needs to ‘re-boot’ its economic model with a Tech-led, ‘supply-side’ miracle to end growth stagnation. Too much debt suffocates an economy, and populates it with zombie enterprises.

In 2014, Jared Bernstein, Obama’s former chief economist said that the U.S. Dollar must lose its reserve status, if such a re-boot were to be done. He explained why, in a New York Times op-ed:

“There are few truisms about the world economy, but for decades, one has been the role of the United States dollar as the world’s reserve currency. It’s a core principle of American economic policy. After all, who wouldn’t want their currency to be the one that foreign banks and governments want to hold in reserve?

“But new research reveals that what was once a privilege is now a burden, undermining job growth, pumping up budget and trade deficits and inflating financial bubbles. To get the American economy on track, the government needs to drop its commitment to maintaining the dollar’s reserve-currency status.”

In essence, this is the Davos Great Reset line. Christine Lagarde, in the same year, called too for a ‘reset’ (or re-boot) of monetary policy (in the face of “bubbles growing here and there) – and to deal with stagnant growth and unemployment. And this week, the U.S. Council on Foreign Relations issued a paper entitled: It is Time to Abandon Dollar Hegemony.

That, we repeat, is the globalist line. The CFR has been a progenitor of both the European and Davos projects. It is not Trump’s. He is fighting to keep America as the seat of western power, and not to accede that role to Merkel’s European project – or to China.

So why would Goldman Sachs say such a thing? Attend carefully to Goldman’s framing: It is not the Davos line. Instead, Currie writes that the soaring disconnect between spiking gold price and a weakening dollar “is being driven by a potential shift in the U.S. Fed towards an inflationary bias, against a backdrop of rising geopolitical tensions, elevated U.S. domestic political and social uncertainty, and a growing second wave of covid-19 related infections”.

Translation: It is about U.S. explosive debt accumulation, on account of the Coronavirus lockdown. In a world where there is already over $100 trillion in dollar-denominated debt, on which the U.S. cannot default; nor will it ever be repaid. It can therefore only be inflated away. That is to say the debt can only be managed through debasing the currency. (Debt jubilees are viewed as beyond the pale.)

That is to say, Goldman’s man says dollar debasement is firmly on the Fed agenda. And that means that “real concerns around the longevity of the U.S. dollar as a reserve currency, have started to emerge”.

It is a nuanced message: It hints that the monetary experiment, which began in 1971, is ending. Currie is telling U.S. that the U.S. is no longer able to manage an economy with this much debt – simply by printing new currency, and with its hands tied on other options. The debt situation already is unprecedented – and the pandemic is accelerating the process.

In short, things are starting to spin out of control, which is not the same as advocating a re-boot. And the debasement of money is inevitable. That’s why Currie points to the disconnect between the gold price (which usually governments like to repress), and a weakening dollar. If it is out of the Fed’s control, it is ultimately (post-November) out of Trump’s hands, too.

Should confidence in the dollar begin to evaporate, all fiat currencies will sink in tandem – as G20 Central Banks are bound by the same policies as the U.S.. China’s situation is complicated. It would in one way be harmed by dollar debasement, but in another way, a general debasement of fiat currency would offer China and Russia the crisis (i.e. the opportunity), to escape the dollar’s knee pressed onto their throats.

And for Gulf States? The slump in oil prices this year already has prompted some investors to bet against Gulf nations’ currencies, putting longstanding currency pegs with the dollar under pressure. GCC states have kept their currencies glued to the dollar since the 1970s, but low oil demand, combined with dollar weakness would exacerbate the threat to Gulf ‘pegs’, as their trade deficits blow out. Were a peg to break, it is not clear there would be any obvious floor to that currency, in present circumstances.

Against such a backdrop, the royal successions underway in Gulf States might perhaps be regarded a sideshow.