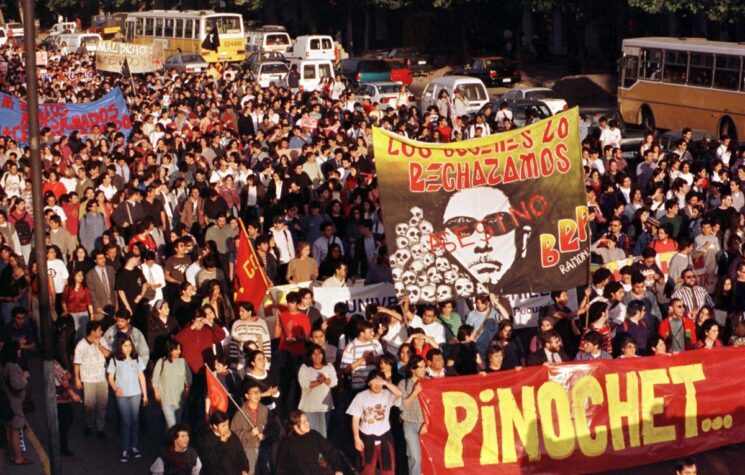

In 1968, the U.S. backed a covert intelligence surveillance campaign in which Latin American right-wing governments conspired to annihilate socialist and communist influence in the region. The plan, known as Operation Condor, was formally implemented in 1975, two years after dictator Augusto Pinochet took power in Chile through a military coup supported by the U.S. Up to 80,000 left wing opponents are estimated to have been killed; 30,000 of them disappeared by right-wing governments in Latin America by 1989, when Operation Condor was officially terminated. Over 400,000 people were detained as political prisoners.

This month marks 44 years since the kidnapping and murder of Spanish-Chilean diplomat Carmelo Soria; also a victim of Operation Condor. Soria, who worked as a UN civil servant and became advisor to the Unidad Popular between 1971 and 1973 when Chile was ruled by socialist President Salvador Allende, became a target for Chile’s National Intelligence Directorate (DINA) during the Pinochet dictatorship. Through his diplomatic immunity as a UN official, Soria aided individuals to seek refuge in embassies until plans for exile could be made.

Soria was kidnapped by DINA agents pertaining to the Brigada Mulchen under the command of Captain Guillermo Salinas at the time, on July 14, tortured at Via Naranja and Villa Grimaldi, and murdered. His body was discovered in Santiago de Chile, dumped in a car that was pushed into a ditch, to cover up the murder as an apparent drunk driving accident.

Little is known about Brigada Mulchen – a secret operatives network with direct links to DINA’s chief Manuel Contreras. The agents comprising Brigada Mulchen have been described by Chilean researcher and author Javier Rebolledo as being part of Pinochet’s inner circle. Michael Townley, a CIA and DINA agent who was tasked with the production and experimentation of sarin gas, together with the biochemist Eugenio Berrios, was involved in Soria’s murder. Townley, who is under the Witness Protection Program in the U.S., was one of the agents requested for extradition by Chile’s Supreme Court for involvement in Soria’s murder. Soria’s remains were exhumed and identified in 2002 by Chile’s Servicio Medico Legal (SML). In 2015, 15 former DINA agents were indicted for Soria’s murder.

In 2019, 43 years after the murder, Chile’s Supreme Court sentenced Pedro Espinoza Bravo, Raul Iturriaga Neumann, Jaime Lele Orellana and Juan Morales Salgado, to a mere six years in prison for Soria’s murder – a travesty of justice which does not even reflect the crime. However, the impunity built through Pinochet’s dictatorship legacy still has a stronghold on Chile. Earlier this year, the Santiago Court of Appeals reduced the prison sentences of 17 former DINA agents who were involved in the murder and disappearances of Communist party members; the latter including Luis Emilio Recabarren.

Espinoza Bravo, sentenced for his involvement in Soria’s murder, is one of the DINA agents whose prison sentences have been reduced. The decision indicates the absence of separation between law and politics in Chile. In his presidential campaign, Chile’s right-wing President Sebastian Pinera had publicly spoken of amnesties for former DINA agents incarcerated for crimes against humanity. The suggestion was well received by the military and right-wing dictatorship supporters, while victims of the dictatorship and their relatives, in a struggle for reclaiming memory and justice since the dictatorship era, had to contend with yet another political impediment – the political manoeuvring at a legal level.

Chile is governed by silence and complicity – the Pinochet legacy, together with the military’s “pact of silence” – remain perpetual obstacles. What has changed since Soria’s murder was passed off as a drunk driving accident at a time when dictatorship opponents were being tortured and disappeared? While the Chilean military has not been averse to such tactics as seen in last year’s protests, it must be said that since Chile’s transition to democracy, subsequent governments have thoroughly failed the cause of human rights and collective memory in the country.