What is most striking about the exceptional measures that have been set in motion in our country (and in many others too) is the inability to see them outside of the immediate context they apparently function in. Hardly anyone seems to have attempted—as any serious political analysis would require—to interpret these measures as symptoms and signs of a broader experiment, in which a new paradigm of governance over people and things is at play.

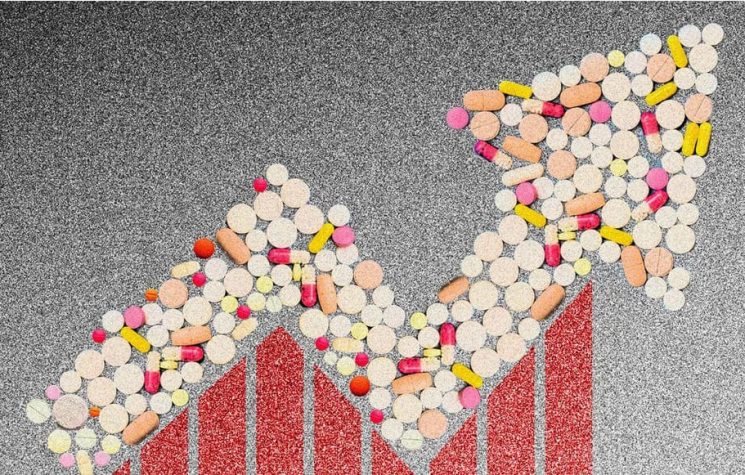

Already in a book published seven years ago (Tempêtes microbiennes, Gallimard 2013)—one that now merits an attentive rereading—Patrick Zylberman described a process by which medical security, previously relegated to the margins of political calculations, was becoming an essential element of national and international political strategies. This involved nothing less than the creation of a sort of “medical terror,” as an instrument of governance to deal with a “worst case scenario.” Even back in 2005, in line with this kind of “worst case” logic, the World Health Organization warned that “avian influenza would kill 2 to 150 million people,” pushing for political responses that nations were not yet prepared to accept at that time.

Zylberman described the political recommendations as having three basic characteristics: 1) measures were formulated based on possible risk in a hypothetical scenario, with data presented to promote behavior permitting management of an extreme situation; 2) “worst case” logic was adopted as a key element of political rationality; 3) a systematic organization of the entire body of citizens was required to reinforce adhesion to the institutions of government as much as possible. The intended result was a sort of super civic spirit, with imposed obligations presented as demonstrations of altruism. Under such control, citizens no longer have a right to health safety; instead, health is imposed on them as a legal obligation (biosecurity).

That which Zylberman described in 2013 has today come to pass quite exactly. It is evident that over and above any emergency connected with a certain virus that could in future make way for another, the design of a new paradigm of government is discernible; one far more effective than any other form of government that the political history of the west has known before.

Due to the progressive decline of ideologies and political convictions, the pretext of security had already succeeded in getting citizens to accept restrictions to their freedom that previously they were unwilling to embrace. Now, biosecurity has taken things further still, managing to portray the total cessation of every form of political activity and social relationship as the ultimate act of civic participation. We have witnessed the paradox of left-wing organizations, traditionally known for demanding and asserting rights and denouncing constitutional violations, unreservedly accepting restrictions to freedom decided by ministerial decrees, devoid of any legality. Even the pre-war fascist government would not have dreamed of imposing such restrictions.

It also seems obvious that so-called “social distancing” will remain a model for the politics that governments have in store for us, as they constantly remind us. It also seems clear (from the pronouncements of the spokespersons of “task forces” consisting of people with flagrant conflicts of interest with their purported roles) that wherever possible this distancing will be leveraged to replace direct human interactions—now so suspect due to the risk of contagion (political contagion, that is)—with digital technologies. As the Ministry of Education, University and Research has already recommended, university classes will be conducted online permanently from next year. Students will not recognize their peers by looking at their faces, which may well be covered by a sanitary mask. Identification will rely instead on digital technologies that process mandatorily relinquished biometric data. Furthermore, every kind of assembly, whether for political motives or simply for friendship, will continue to be prohibited.

The entire concept of human destiny is at stake and we face a future that is tinged with a sense of apocalypse, of the end of the world—an idea adopted from our old religions, now nearing their twilight. Just as politics was superseded by the economy, now the economy too will have to be integrated into the paradigm of biosecurity, for the purpose of enabling government. All other needs must be sacrificed. At this point it is legitimate to ask ourselves whether such a society can still be defined as human, or whether the loss of physical contact, of facial expressions, of friendships, of love can ever be worth an abstract and presumably spurious medical security.