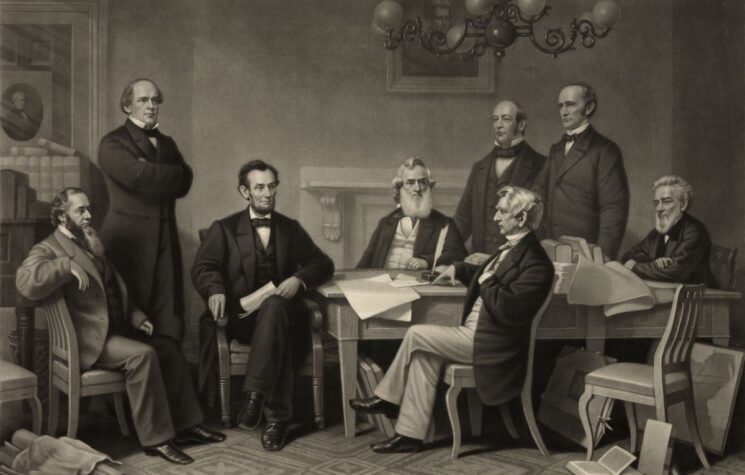

The relatively smooth waters of cooperation between FDR, Churchill, and Stalin at Yalta concealed roiling cross currents beneath the glistening surface which some historians like to emphasise. These rip tides were quick to erupt in the last weeks of the war.

Much has been written over the years about the wartime Yalta conference, and more ink will no doubt be spilled this year, on its 75th anniversary. Yalta was supposed to mark the beginnings of post-war Anglo-American-Soviet cooperation. Plans were discussed for the United Nations. Germany was to be sorted out so it would not again threaten European security. Reparations in kind were to be paid to the USSR to help rebuild the country. Poland was to be moved westward with a new government acceptable to the Big Three allies. The USSR would come into the war against Japan, and so on. The atmosphere at the meetings was cordial, but the cordiality did not last long. All the high hopes were soon dashed, and then followed by a welter of recriminations. Naïve, sick Franklin Roosevelt (FDR) caved in to Joseph Stalin. Or FDR betrayed Winston Churchill. Or Churchill and FDR abandoned Poland to communism. Or… and this is perhaps the more common view in the West, Stalin betrayed the Grand Alliance and duped his partners. Yalta, whichever way you look at it, did not lead to those “broad, sunlit uplands”, as Churchill put it, on which many pinned their hopes.

The Russian government likes to remind people in the West of the Grand Alliance against Nazi Germany with a view to improving relations in the present for some new common cause, or simply because there is no other alternative. One can understand that need and the reasoning, and more power to the Russians for trying, but as a historian I follow the trails of evidence wherever they lead.

In November 1933 FDR and Maksim M. Litvinov, then commissar (narkom) for foreign affairs, negotiated US recognition of the USSR.

If only things had been different. For example, if only FDR had not suddenly died on 12 April 1945, and if only Harry Truman had not become US president. I am not sure FDR’s continued presence in the White House would have mattered one way or the other. In November 1933 FDR and Maksim M. Litvinov, then commissar (narkom) for foreign affairs, negotiated US recognition of the USSR. Both Roosevelt and Stalin wanted to close a deal, especially on outstanding debts from the revolutionary period. This would have allowed wider cooperation on “political” issues, mainly security against Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan. If these two powerful leaders wanted to get on better terms in 1933, a Soviet-American rapprochement should have started in that year, and not in 1941. What happened? The State Department, full of Sovietophobes, intervened to scuttle the start made by FDR and Litvinov. Would it have been any different in 1945, had Roosevelt lived?

It was not just the anti-communists in the United States, who opposed postwar cooperation with the USSR; there were also Sovietophobes in London. Anglo-Soviet relations were almost always bad from 1917 to 1941. After the Bolsheviks seized power in November 1917 the British government sent troops to the far distant corners of Russia and paid out more than a £100 million pounds to support the White Guard resistance against Soviet Russia. This was not beer money. If it had been up to Winston Churchill, then secretary of state for war (from January 1919), a lot more would have been done to overthrow the Bolsheviks. After the failure of the Allied intervention in 1920-1921, there were occasional attempts to improve Anglo-Soviet relations which never went very far.

The best chance came in 1934 when Sir Robert Vansittart, Permanent Undersecretary of the Foreign Office, and Ivan M. Maisky, the Soviet polpred, or ambassador in London, started talking about a rapprochement in the summer of 1934. The motivation for both was the rising menace of Nazi Germany, as it was for FDR and Litvinov. In March 1935 Anthony Eden, then Lord Privy Seal, went to Moscow, to meet Stalin, Vyacheslav M. Molotov, Litvinov and others. Litvinov wanted to talk about the Nazi danger, but Eden preferred generalities. Litvinov and Maisky thought Eden was on their side, but they were wrong. When he became Foreign Secretary at the end of the 1935, he almost immediately put the brakes on the Anglo-Soviet rapprochement.

Maisky, the Soviet polpred, or ambassador in London

Why would Eden do that? It was the usual anticommunism amongst the British governing elite, the usual Sovietophobia. Anglo-Soviet relations never got beyond this false start even as the Nazi threat to peace increased through the various crises of the late 1930s. At the Munich conference in September 1938 the British and French governments sold out Czechoslovakia for five months of false security. They had ambitions for much more with Herr Hitler, but he bitterly disappointed them.

And finally there were the last chance negotiations in 1939 to organise an Anglo-Franco-Soviet front against Nazi Germany. In April the Soviet government made new alliance offers, and put them in writing to make a point. Even then however, as astonishing as it might seem now, Britain and France failed to seize the opportunity to close a deal with Moscow. British and French leaders were just not serious about an anti-Nazi entente with the USSR in spite of Churchill’s warning in the House of Commons that without the Red Army, France and Britain had no chance in a war against Hitler.

Litvinov wanted to talk about the Nazi danger, but Eden preferred generalities

In May Stalin sacked his stalwart narkom Litvinov. It should have been a wake-up call in London and Paris, but wasn’t. You could not blame Stalin for dismissing Litvinov. He was mocked in the west. He had tried since 1933 to organise an anti-Nazi bloc. It was the Grand Alliance That Never Was. This was not a personal policy, by the way, but Soviet policy approved by Stalin. All the USSR’s prospective allies had abandoned Moscow one after the other: the United States, France, Italy (yes even fascist Italy), Britain, and Romania. Even the dodgy Czechoslovaks were unreliable. Poland of course always stood against cooperation with the USSR. In July 1939 British officials were caught still talking with German counterparts about a last minute détente.

In August 1939 British and French delegations finally went to Moscow to negotiate terms of an alliance. They travelled on a slow chartered merchantman, without authority to conclude an agreement, but with instructions to “go very slowly”. “With empty hands,” said the French chief negotiator. The clock was ticking down to war, and still the British and French were not serious with their assumed Soviet allies.

You know what happened next. Stalin bailed himself out by concluding the non-aggression pact with Hitler. Nothing to be proud of, mind you, but what options did he have? Trust the French? Trust the British? They were not serious, and you don’t go to with war with allies who are not serious. What would you have done? Of course, the British and French blamed Stalin for the failure of negotiations. And so have generations of western historians and more recently politicians. It was an audacious Pot calling Kettle black.

In September 1939 the Wehrmacht invaded Poland and defeated it in a matter of days. In May 1940 France was knocked out of the war, lasting only a little longer than Poland had done. Couldn’t the French have fought a little? Stalin asked his colleagues at the time. And the British, how could they let this happen? Now Hitler is going to beat our brains out, Stalin rightly feared.

On 22 June 1941 Hitler invaded the USSR. Every intelligence agency in Europe knew that Hitler was going to attack. The various Soviet agencies knew too and kept Stalin well informed. He must have been about the only leader in Europe who did not believe that Hitler would invade. The British and Americans reckoned that the Red Army would hold out for 4 to 6 weeks. Not much optimism there. The British of course were projecting from their own experience. They had yet to beat the Wehrmacht in battle.

David Low, the celebrated British cartoonist, drew an image, asking when Britain would offer real help instead of rhetorical flowers of praise.

Churchill broke out cigars and cognac when Germany attacked the USSR. You can always count on Winston for a good quote: “If Hitler invaded Hell, I would at least make a favourable reference to the Devil.” On other matters he was not so eager in spite of a grand speech on BBC the evening of 22 June. There was a big debate inside the government about whether the Soviet national anthem, the Internationale, should be played on BBC radio on Sunday evenings along with the anthems of other British allies. The government at first refused to approve, not wanting to appear to be endorsing socialist revolution. A touchy subject, Winston was adamant until after the Soviet victory before Moscow in December 1941. Eden, again Foreign Secretary, asked the PM to relent. “All right,” Churchill wrote on Eden’s note. Churchill had a hard time deciding whether the Russians were “barbarians” or allies, even when he needed them most.

That summer of 1941 Britain began to ship war matériel to the USSR. Not much mind you, but better than nothing. Britain was still not in a position to offer important assistance. When Stalin suggested that Britain send troops to fight on the Soviet front, Churchill would have nothing to do with it, though others in London felt guilty because the Red Army was doing all the fighting. The Foreign Office suggested an evasive reply. David Low, the celebrated British cartoonist, drew an image, asking when Britain would offer real help instead of rhetorical flowers of praise. In early July 1941 Maisky, the Soviet polpred, raised the question of a second front in France. That too was out of the question.

Did the British want to fight to the last Red Army soldier? David Low wondered in a cartoon where ‘Colonel Blimp’, the proverbial rotten British Tory, and his cronies sat watching from afar the war in the east. You could hardly blame Stalin for accusing the British of shirking the fight during the late summer and autumn of 1942 with the battle of Stalingrad raging. Churchill and Roosevelt made careless promises about a second front which they could not or would not keep.

During the summer of 1941 Roosevelt got involved after sitting on the sidelines, worried about the “isolationist”, anti-communist opposition. The Soviet polpred in Washington reported obstacles in obtaining US assistance, but then he noted an improvement in the atmosphere. In November 1941 FDR announced that “Lend-Lease” supplies would go to the USSR. The Grand Alliance began to form up. Roosevelt became Godfather of the Big Three.

David Low wondered in a cartoon where ‘Colonel Blimp’, the proverbial rotten British Tory, and his cronies sat watching from afar the war in the east.

After the Soviet victory before Moscow in December 1941 the Foreign Office debated what impact it would have on the course of the war. Stalin could opt out of the war leaving Britain and the US in the lurch. Sir Orme G. Sargent and Sir Alexander Cadogan, senior Foreign Office officials, were great Sovietophobes. Historians can always count on them for something nasty to say about the USSR. In early February 1942 they were worried about the outcome of the war. They feared that the Red Army might win without any help from the west. According to Cadogan and Sargent, that would be a catastrophe. Britain would have nothing to say about the post-war order.

Here is what Cadogan had to say on 8 February 1942: “… we ought to hope for continued pressure by the Soviet, with erosion of German manpower & material and not too [emphasis in original] great a geographical advance.”

Eden responded on the same day: “… it remains broadly true that a German collapse this year will be an exclusively Soviet victory with all that implies. Therefore clearly we must do all in our power to resolve grievances & come to terms with [Stalin] for the future. This may also prevent him from double crossing us, but it will at least remove pretexts. He has these now…” Britain had no armies in Europe, fighting the Germans.

The Foreign Office had two big worries in February 1942: the Red Army winning too quickly and Stalin double-crossing them. Can you imagine? The Red Army had already suffered more than 3 million casualties, not to speak of civilian losses, and the Foreign Office was worried about the Red Army winning too quickly.

Pragmatist that he was, Churchill knew what he had to do. He threw some flowers to Stalin: “Words fail me to express the admiration which all of us feel at the continued brilliant successes of your Armies against the German invader, but I cannot resist sending you a further word of gratitude and congratulation on all that Russia is doing for the common cause.”

Philip Faymonville, the Brigadier in charge of Lend-Lease, got on well with his Soviet counterparts which did not sit well with the US military attaché, Joseph Michela

In July 1941 the British and Soviet governments exchanged military missions. The first three British heads of mission were a failure. They were Generals Frank Noel Mason-Macfarlane, Giffard Martel and Brocas Burrows. The latter two officers were true blue Sovietophobes. General Burrows had been in Murmansk during the British intervention in 1918-1919. Burrows could not hide his hatred of the USSR. He wanted to wear medals he had got from the White Guard armies. The Foreign Office reluctantly let him do it. Burrows only lasted a few months in Moscow before Stalin himself asked for his recall.

There was also trouble in the US embassy in Moscow. The Brigadier in charge of Lend-Lease was Philip Faymonville. He got on well with his Soviet counterparts which did not sit well with the US military attaché, Joseph Michela. Brigadier Michela hated the USSR and disdained the Red Army. He was wrong about Soviet capabilities and intentions in just about every report he sent to Washington. What on earth was he doing in Moscow? In 1942 he accused Faymonville of being a homosexual, blackmailed, he implied by Soviet intelligence. The FBI investigated and found nothing but praise for Faymonville. Michela was a good hater and hated “the pinks” in the US government who supported the Soviet war effort. That also included FDR since it was his policy to support the USSR. The US embassy in Moscow was infested with Sovietophobes; and it was civil war between Michela and Faymonville. In 1943 they were recalled to Washington.

In the summer of 1944 Sovietophobia in the British War Office was so intense that it worried the Foreign Office. Stalin was certain to hear of it. In August 1944 the Chiefs of Staff were talking about the USSR as “enemy no. 1”. This was a reversion back to the 1930s when western elites could not decide if the USSR or Nazi Germany was “enemy no. 1.” The Foreign Office was greatly alarmed by the inability of British senior officers to conduct themselves “diplomatically” with their Soviet counterparts. To quote the head of the Northern Department, Christopher F. A. Warner, “Anglo-Russian post-war relations will be irretrievably prejudiced with the most appalling results for perhaps 100 years. This is altogether too high a price to pay for the prejudices of the Chief of the Imperial General Staff [Field Marshal Sir Alan Brooke]”. Even Churchill had trouble restraining his old anti-Bolshevik urges, shocking his colleagues at times with outlandish comments about communist crocodiles and Russian barbarians.

Russophobia and Sovietophobia were alive and well in the higher ranks of the British and US armed forces even as the Red Army was crushing the Wehrmacht. And that was not all. In June 1944 Stalin proposed the formation of a Tripartite Military Commission to coordinate military planning with the western allies, they having finally landed in Normandy. After months of delays, the proposal was abandoned because of foot dragging by the British Chiefs of Staff.

British army hostility also manifested itself in planning for the post-war period. In several major planning documents prior to the end of the war you can follow the revisions to these papers where the authors slipped in preoccupations about a potential Soviet threat to British interests in the post-war period.

All of this occurred in the lead-up to the Yalta conference. The relatively smooth waters of cooperation between FDR, Churchill, and Stalin at Yalta concealed roiling cross currents beneath the glistening surface which some historians like to emphasise. These rip tides were quick to erupt in the last weeks of the war.

In March 1945 there was a row over secret Anglo-American negotiations in Berne, Switzerland with German military representatives for the surrender of German forces in northern Italy. In late March Molotov, narkom for Foreign Affairs, accused the Anglo-Americans of going behind the back of the Soviet Union. In early April German resistance in the west collapsed, though not in the east. It looked like the Red Army was going to have to bear most of the casualties again in reducing the last German forces. The Soviet side must have wondered if there was a connection between the March negotiations in Switzerland and the end of German resistance in the west.

In the Foreign Office, Sargent, Deputy Permanent Undersecretary, took offence at Soviet irritation. It’s time for “a showdown” with Moscow, he wrote in early April 1945. A “showdown,” he said. We’ve put up with the Soviet for a long time because they were carrying the brunt of the fighting, but since the German collapse in the west, things have changed. We can start setting conditions for the Soviet side, Sargent wrote. What is interesting about his memorandum is that he already anticipated the division of Europe between east and west. We’re going “to rehabilitate” Germany, Sargent wrote, as we did Italy “so as to save her from Communism.”

“They [the USSR] may well decide that there is not a moment to be lost in consolidating their cordon sanitaire, not merely against a future German danger, but against the impending penetration by the Western Allies.” Godfather Roosevelt quieted down the row over the Berne negotiations just before his death on 12 April. US Ambassador Averill Harriman and the US head of the military mission in Moscow, General John R. Deane, then rushed to Washington, to obtain, in effect, the abandonment of FDR’s policy toward the Soviet Union.Roosevelt’s ghost could not do much against the zeal of subordinates who were determined to set matters straight with the USSR.

Not to be outdone, Churchill ordered the Joint Planning Staff to draw up contingency plans for war against the USSR. Yes, that is correct, for war against the USSR. This astonishing, scandalous document was entitled Operation “Unthinkable” and dated 22 May 1945, three months after Yalta. It was classified “top secret”, and you can understand why. The document foresaw the contingency of military action against the Red Army only a fortnight after VE Day, making use of reconstituted German divisions to be allied with British and US forces. “The overall or political object is to impose upon Russia the will of the United States and British Empire.” Of course, we’ll offer the Russians a choice, said the document, but “if they want total war, they are in a position to have it.” The War Office weeders really slipped up when they did not destroy this particular document. I have never seen in British archives so much stupidity, so many wild ideas, packed into one 29pp. document. General Hastings Ismay, the PM’s military advisor, wrote to Churchill in early June that the document was “bare facts”. The Chiefs of Staff felt that “the less that was put on paper… the better.” Churchill replied that the paper was a “precautionary study of what, I hope, is still a purely hypothetical contingency.” That sounded like backpedaling.

You will find this extraordinary document in the British National Archives at Kew in a Cabinet file entitled “The Russian Threat to Western Civilisation”. My guess is you can also find fresh files like this one, dated 2014 or after, in top secret US and British government vaults. Foreign Office official Warner was more right than he knew when he wrote about the danger of 100 years of Anglo-Russian hostility. If one starts the clock ticking in 1917, we are at 103 years and counting.

This is why I propose that the Yalta conference was a mirage, brilliant to be sure, but still a mirage. As soon as the German danger subsided, it was back to business as usual in the West. The Grand Alliance was over—it was a “truce”, some of my students have said. The cold war, which began after 1917, then gradually resumed in the spring of 1945. Count the years since 1917 when the USSR and Russia have had good relations with the west and with the United States in particular. Four years out of 103 leaves not quite a century of hostility, and this does not bode well for change in the foreseeable future. It is best to see things as they are, and not as you might wish them to be.