Tareq HADDAD

A mafia runs editors. Freedom of the press is dead. Journalists and ordinary people must stand up.

INTRODUCTION

Until several days ago, I was a journalist at Newsweek. I decided to hand my resignation in because, in essence, I was given a simple choice. On one hand, I could continue to be employed by the company, stay in their chic London offices and earn a steady salary—only if I adhered to what could or could not be reported and suppressed vital facts. Alternatively, I could leave the company and tell the truth.

In the end, that decision was rather simple, all be it I understand the cost to me will be undesirable. I will be unemployed, struggle to finance myself and will likely not find another position in the industry I care about so passionately. If I am a little lucky, I will be smeared as a conspiracy theorist, maybe an Assad apologist or even a Russian asset—the latest farcical slur of the day.

Although I am a British citizen, the irony is that I’m half Arab and half Russian. (Bellingcat: I’m happy to answer any requests.)

It is a terribly sad state of affairs when perfectly loyal people who want nothing but the best for their countries are labelled with such preposterous accusations. Take Iraq war veteran and Hawaii congresswoman Tulsi Gabbard for example, who was the target of such mud slinging for opposing U.S. involvement in Syria and for simply standing up to the Democratic Party’s most corrupt politician, Hillary Clinton. These smears are immature for a democracy—but I, in fact, welcome such attacks.

When the facts presented are utterly ignored and the messengers themselves are crucified in this way, it signals to right-minded people who the true perpetrators of lies are and where the truth in fact lies.

That truth is what matters most to me. It is what first drove me to journalism while I was working in Jersey’s offshore finance industry after completing my degree from Binghamton University’s School of Management in upstate New York. I was so outraged when I grew to realize that this small idyllic island I love and had grown up on since the age of nine, a British Crown dependency fifteen miles off the coast of France, was in fact a hub for global tax evasion. This realization came to me while the British people were being told that austerity had to continue—public funding for schools, hospitals, policing and all matter of things were to be slashed—all while the government “recovered” after bailing out the banks following the 2008 crash. That austerity lie was one I could no longer stomach as soon as I came to understand that my fairly uninspiring administrative role was in fact a part of this global network of firms to help multinational companies, businessmen, politicians and members of various royal families in avoiding paying trillions in tax—all under a perfectly legal infrastructure that the government was fully aware of, but kept quiet about.

In my naivety, as I left that industry and began my journalism training, I wrote a piece that detailed some of this corruption in hopes of changing the public awareness around these issues and in hopes that they no longer continued—albeit I did so in a manner of writing and sophistication I would be embarrassed of presently—but to my disappointment at the time, the piece was hardly noticed and the system remains little changed to now. Nonetheless, since that moment, I have not once regretted speaking truthfully, most especially for my own mental wellbeing: I would not have been able to regard myself with a grain of self-respect had I continued to engage in something I knew was a lie. It is the very same force that compels me to write now.

There is also another, deeper force that compels me to write. In my years since that moment when I decided to become a journalist and a writer, although I suspect I have known it intrinsically long before, I have come to learn that truth is also the most fundamental pillar of this modern society we so often take for granted—a realisation that did not come to us easily and one that we should be extremely careful to neglect. That is why when journalistic institutions fail to remember this central pillar, we should all be outraged because our mutual destruction follows. It may sound like hyperbole, but I assure you it’s not. When our record of where we come from is flawed, or our truth to put it more simply, the new lies stack on top of the old until our connection to reality becomes so disjointed that our understanding of the world ultimately implodes. The failure of current journalism, among other factors, is undoubtedly linked to the current regression of the Western world. In consequence, we have become the biggest perpetrators of the crimes our democracies were created to prevent.

Of course, for those who pay attention, this failure of mainstream journalism I speak of is nothing new. It has been ongoing for decades and was all too obvious following the Iraq war fiasco. The U.S. and U.K. governments, headed by people who cared for little other than their own personal gain, told the people of their respective countries a slew of fabrications and the media establishment, other than a handful of exceptions, simply went along for the ride.

This was something that consumed my interest when I was training to be a journalist. How could hundreds of reputable, well-meaning journalists get it so wrong? I read numerous books on the issue—from Noam Chomsky’s Manufacturing Consent and Philip Knightley’s The First Casualty to work by Chris Hedges, the Pulitzer-prize-winning former foreign correspondent for the New York Times who was booted out for opposing that war (who I disagree with on some things, for the record)—but still, I believed that honest journalism could be done. Nothing I read however, came close to the dishonesty and deception I experienced while at Newsweek. Previously, I believed that not enough journalists questioned the government narrative sufficiently. I believed they failed to examine the facts with close enough attention and had not connected the dots as a handful of others had done.

No. The problem is far worse than that.

SYRIA

In the aftermath of the Iraq war and during my time studying this failure of the media since, I was of course extremely aware of the high likelihood that the U.S. government narrative on Syria was a deception. For starters, there were the statements made by the retired four-star general, General Wesley Clark, to Democracy Now’s Amy Goodman in 2007, four years prior to the beginning of the Syria conflict. The following is worth watching to in full.

Nonetheless, once I joined IBTimes UK in 2016, after training with the Press Association and working at the Hull Daily Mail (both of whom I am eternally indebted to for giving me an excellent foundation for starting my career) I solidly understood that journalism was not the profession of making unverifiable claims. I, or any journalist for that matter, could not out-right say that the nature of the Syrian conflict was based on a lie, no matter how strongly we suspected it. To do so, we would need unshakeable evidence that pointed to this.

Through the years, good journalists did document evidence. Roula Khalaf, who will soon take over from Lionel Barber as the editor of the Financial Times, wrote one such piece alongside Abigail Fielding-Smith in 2013. It documented how Qatar provided arms and funded the opposition of Bashar al-Assad’s legitimate government to the tune of somewhere between $1 and $3 billion from the outset of the conflict, rubbishing claims that it was a “people’s revolution” that turned violent. Footage captured by Syrian photographer Issa Touma—made into a short film titled 9 Days From My Window in Aleppo—similarly showed how Qatar-funded jihadists from the Al-Tawhid Brigade were present in the streets of Syria’s capital from the very outset of the war.

“Fighters re-enter my street,” Touma says as he films covertly out of his window. “They look different. They are heavily armed men with beards. I had only heard about them before. This is Liwa al-Tawhid. National television calls them terrorists. The international press calls them freedom fighters. I don’t care what they call it—I refuse to chose a side. But it’s a lie that the revolution started peacefully everywhere. At least in my street, Al Said Ali Street, it started with guns. It didn’t start peacefully at all.”

Veterans of the trade Seymour Hersh and Robert Fisk also poked holes in the U.S. government narrative, but their treatment by other journalists has been one of the most shameful episodes in the history of the press.

Hersh—who exposed the My Lai Massacre during the Vietnam War, the clandestine bombing of Cambodia, the torture at Abu Ghraib prison, in addition to telling the world the real story of how Osama Bin Laden died—was shunned from the industry for reporting a simple fact: Bashar al-Assad’s government is not the only actor with access to chemical weapons in Syria. After a sarin attack in the Damascus suburb of Ghouta in 2013, he was further smeared for reporting that Barack Obama withheld important military intelligence: samples examined in Britain’s Porton Down did not match the chemical signatures of sarin held in the Syrian government’s arsenals.

Fisk, writing days before the Syrian conflict escalated, in a piece that asked Americans to consider what they were really doing in the Middle East as the ten-year anniversary of 9/11 approached, also raised important questions, but he too was largely ignored.

I also did my best to document evidence that poked holes in the narrative as best I could. In 2016, I wrote how Egyptian authorities arrested five people for allegedly filming staged propaganda that purported to be from Syria. Though I’m not aware of any evidence to suggest that the two are connected and I make no such claims, these arrests came to light after The Bureau of Investigative Journalism and The Sunday Times revealed that a British PR firm, Bell Pottinger, was working with the CIA, the Pentagon and the National Security Council and received $540 million to create false propaganda in Iraq a month prior.

The following year, after the alleged chemical weapons attack in Khan Sheikhoun, I documented the intriguing story of Shajul Islam,the British doctor who purported to have treated the alleged victims and appeared on several television networks including NBC to sell the case for retaliation. He gushed with heroism, but it was not reported he was previously charged with terror offences in the U.K. and was in fact considered a “committed jihadist” by MI6. He was imprisoned in 2013 in connection with the kidnapping of two Western photo-journalists in northern Syria and was struck off Britain’s General Medical Council in 2016. Why he was released without sentencing and was allowed to travel back to Syria remains a mystery to me.

I also refused to recycle the same sloppy language used, inadvertently or not, by a number of other publications. Al Qaeda and their affiliates had always been referred to as terrorists as far as I was aware—why the sudden change to “rebels” or “moderate rebels” for the purposes of Syria? Thankfully, the news editor I worked with most frequently at the time, Fiona Keating, trusted my reporting and had no problems with me using the more appropriate terms “anti-Assad fighters” or “insurgents”—though one could arguably say even that was not accurate enough.

When buses carrying civilian refugees hoping to escape the fighting in Idlib province were attacked with car bombs in April of 2017, killing over 100, most of them women and children, I was disappointed with the Guardian and the BBC for continuing with their use of this infantile word, but this was not the language I felt to be appropriate in my report.

At roughly the same time, in light of the Khan Sheikhoun attack, confronted with an ever-growing list of irregularities and obvious falsifications—such as increasing evidence that the White Helmets were not what they purported of being, or the ridiculousness that the Western world’s de facto authority on Syria had become 7-year-old Bana al-Abed—I wrote an opinion piece that came short of calling the narrative around the Syrian conflict a lie, but simply pleaded that independent investigations of the alleged chemical weapons attack were allowed to take place before we rushed head first into war. I still believed honesty would prevail.

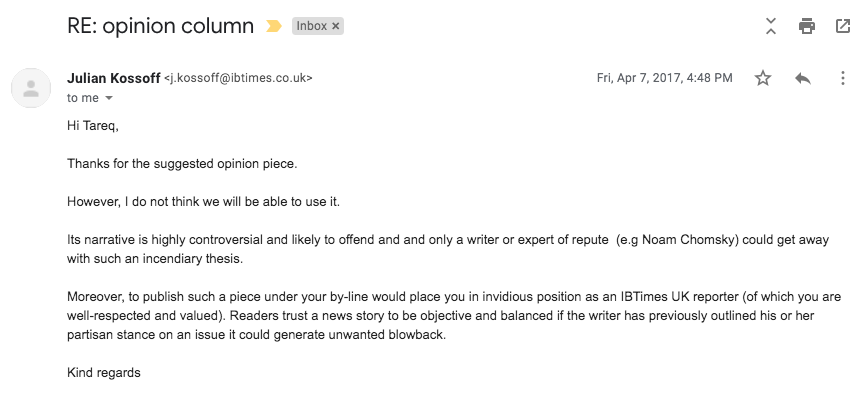

That piece was ultimately declined by IBTimes—though I covertly published it in CounterPunch later—but the rejection email I received from the editor-in-chief at the time makes for interesting reading.

I was sad to hear that asking for an independent investigation into a chemical weapons attack was an “incendiary theory,” but I was forced to move on.

I was sad to hear that asking for an independent investigation into a chemical weapons attack was an “incendiary theory,” but I was forced to move on.

By that summer, I was let go alongside a number of other journalists from the publication after the Buzzfeed-style model of click-bait-aggregation journalism was heavily punished by a new Google algorithm and had largely failed: page views plummeted and editors couldn’t seem to understand it was because we weren’t doing any real journalism. Having felt frustrated with the industry, I decided to not pursue another position in reporting and decided to move to mainland Europe in hopes of pursuing my other passion—literature—with aspirations of being able to write more freely.

Fast forward to 2019, I decided to return to journalism as I was feeling the pressure to have “a grown-up job” and could not count on my ability to be a novelist as a means of long-term career stability. So when I joined Newsweek in September, I was extremely thankful for the opportunity and had no intention of being controversial—the number of jobs in the industry appeared to be shrinking and, besides, the Syrian conflict appeared to be dying down. As soon as I arrived, Newsweek editor-in-chief Nancy Cooper emphasised original reporting and I was even even more pleased. I wanted to come in, get my head down and start building my reputation as a journalist again.

Then on October 6, President Donald Trump and the military machine behind him threw my quiet hopes of staying well clear of Syria into disarray. He announced the decision to withdraw U.S. troops from the country and green-lit the Turkish invasion that followed in a matter of days. Given my understanding of the situation, I was asked by Newsweek editors to report on this.

Within days of the Turkish invasion into Syria beginning, Turkey was accused of using the incendiary chemical white phosphorus in an attack on Ras al-Ayn and, again, having pitched the story, I was asked to report on the allegations. This spurred a follow-up investigation on why the use of the substance—a self-igniting chemical that burns at upwards of 4,800 degrees Fahrenheit, causing devastating damage to its victims—was rarely considered a war crime under the relevant weapons conventions and I was commended by Nancy for doing excellent journalism.

It was while investigating this story that I started to come across growing evidence that the U.N.-backed body for investigating chemical weapons use, the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), issued a doctored report about an alleged chemical attack in Douma in April of 2018, much to the anger of OPCW investigators who visited the scene. Once Peter Hitchens of the Mail on Sunday published his story containing a leaked letter that was circulated internally from one of the disgruntled OPCW scientists, I believed there was more than enough evidence to publish the story in Newsweek. That case was made even stronger when the letter was confirmed by Reuters and had been corroborated by former OPCW director-general Dr. Jose Bustani.

Although I am no stranger to having story ideas rejected, or having to censor my language to not rock the ship, this was a truth that had to be told. I was not prepared to back down on this.

Let me be clear: there is evidence that a United Nations body—whose jurisdiction was established after the world agreed to never repeat the horrors of World War I and World War II, such as German forces firing more than 150 tons of chlorine gas at French colonial troops in Ypres—is being weaponized to sell the case for war.

After OPCW experts found trace levels of chlorine when they visited Douma—i.e. no different than the levels of chlorine normally present in the atmosphere—or raised concerns that the canisters may have been tampered with or placed, both of which were reflected in their original reports, they made protestations because this information was withheld from the final report that was released to the world’s media. Instead, the final wording said chlorine was “likely” used and the war machine continued.

This is not a “conspiracy theory” as Newsweek sadly said in a statement to Fox News—interestingly the only mainstream publication to cover my resignation. Real OPCW scientists have met with real journalists and explained the timeline of events. They provided internal documents that proved these allegations—documents that were then confirmed by Reuters. This is all I wanted to report.

Meanwhile, OPCW scientists were prevented from investigating Turkey’s alleged use of white phosphorus. This flagrant politicization of a neutral body is opening the world up to repeating the same horrors we experienced in those two devastating wars.

This is unacceptable and I resigned when I was forbidden from reporting on this.

NEWSWEEK SUPPRESSION: A TIMELINE OF EVENTS

I first became aware of the Mail on Sunday report on Monday, November 25, and this is when I raised it with Alfred Joyner, Newsweek’s global executive producer, who had been my main point of contact for pitching stories.

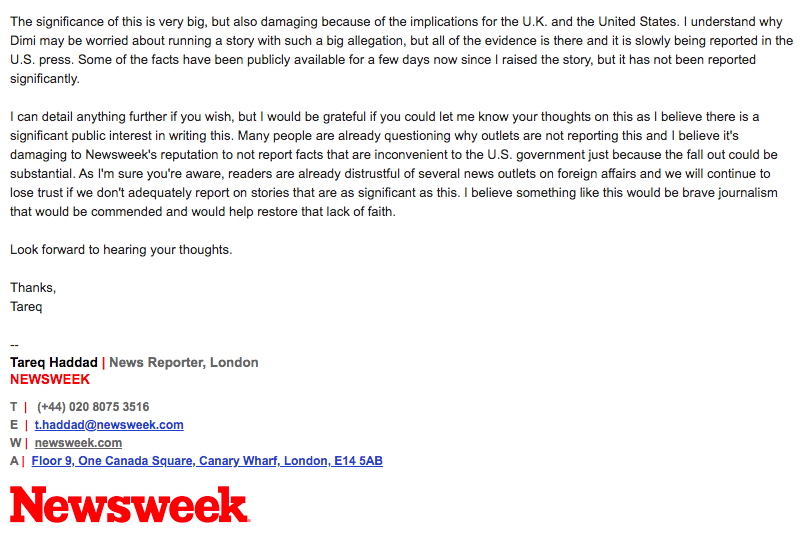

Following a conversation with Alfred, he asked me to write the pitch in a note to him and Newsweek’s foreign affairs editor, Dimi Reider, on the company’s internal messaging system. The following is a copy and paste of that pitch, alongside the conversation that followed in the next few days.

Once I returned to the office on Thursday, November 28, I proceeded to have a conversation with Dimi, but to my disappointment, he did not address any of my protestations against why the article could not be published. He made the famous joke about former Soviet politician Leonid Brezhnev irrelevantly, one he had already made to me a couple of weeks before, and after listening to my reasoning for wanting to have the story published for several minutes, all he had to say was: “I’m sorry, but I’m afraid it’s a no.”

The following morning, feeling incredibly frustrated, I wrote an email to Nancy and Newsweek’s digital director and London bureau chief, Laura Davis, to express my concerns.

Several stressful days passed where I did not hear from either Laura or Nancy, but in the meantime, as I tried to continue as best as I could with my every day reporting role, I noticed how an entertainment editor by the name of Tufayel Ahmed began to pick up most of the following stories I wrote.

In my experience of working with editors in the past, if an issue ever arose with a story, we would have a perfectly civil conversation, I would make the relevant adjustments where necessary and the article would be published without further problems. That was not my experience with Tufayel.

At first, when he sent me long, overly critical and often hostile criticisms on articles I wrote, I considered asking him to step into a meeting room in order to ask him whether I had inadvertently done something to offend him. Having come from a newspaper background where mistakes in articles required embarrassing apologies printed in the paper the next day, and having held the belief that editors were your best friend and should always be kept on side, I always prided myself in filing copy that was free of any errors and throughout my career, I was frequently commended for doing exactly this.

In my time at the Hull Daily Mail for example, regarded as one of the U.K.’s best regional newspapers, I do not recall a single correction being printed on any of the articles I wrote. That was the case despite covering murder trials, rape cases and numerous other sensitive stories.

On the eve of the Brexit referendum, despite still being a trainee reporter, I had built such a reputation for my accurate journalism and my attention-to-detail skills that I was even entrusted to single-handedly edit and publish copy from two politics reporters to the publication’s website, while managing the live blog, all social media channels and filing my own stories on national developments as the results came in. The following morning, following a short nap, the editor was so impressed with my efforts that I was asked to conduct the interviews with the local leaders of each political party, despite being one of the most junior reporters on the team.

Furthermore, in close to 1,000 published articles for IBTimes UK, I can only recall one incident where an article required a correction. An Israel lobby group—forgive me for being unable to recall which one—objected to my use of the word “settlements” and requested that it be replaced with “settlement units” instead. This was a reasonable request and the article was updated to reflect this without further incident.

I do not say these things to be self-congratulatory. I say these things because I was deeply saddened and disturbed. Because when I finally received a response from Laura about the OPCW story on December 5, six days after my initial email and after repeated attempts to speak to her in person, only one paragraph was devoted to the leaked letter and the rest of the email attacked my capability as a journalist.

It listed all the instances that Tufayel had criticised me on, unfairly mischaracterising my actions, in addition to listing one genuine mistake I made in the course of everyday reporting—something not to be unexpected when every day I was expected to write four stories, often about complicated topics, sometimes with no prior experience in them. Nonetheless, even for this story, I had taken immediate action needed to resolve and had apologised to editors at the time, the characterisation of what took place in Laura’s email was deeply maligned.

That was the moment I knew beyond doubt what my gut had been telling me before: there was no valid reason for this OPCW story not to be published. It was simply being suppressed. I was being attacked for pushing back against this.

As I have nothing to hide, I will publish Laura’s response in full.

You will see my full response in due course, but first, some further comments about Laura’s criticisms must be addressed.

EDITORS AT FAULT

My first “indiscretion” is rather simple to address. I believe—however I must admit I am not certain, as the information was never published—that the article Laura is referring to this. Regardless of which piece it was, the following events took place.

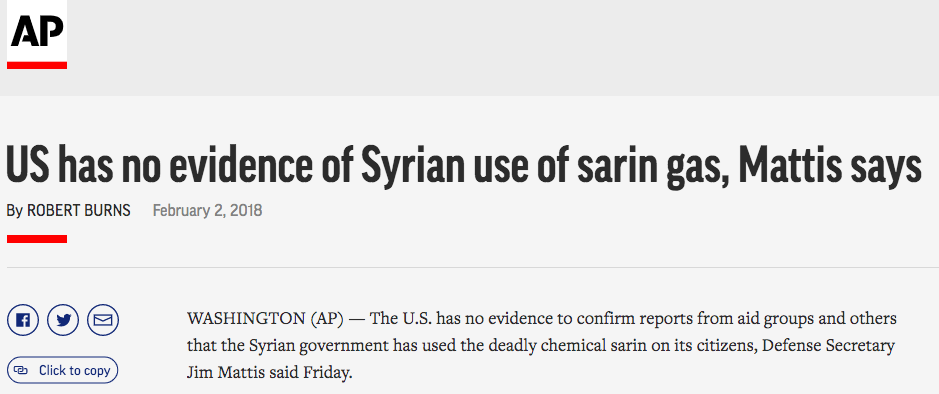

In 2018, confirming the earlier reporting by Hersh, former Defense Secretary Jim Mattis announced that the Pentagon has no evidence to support the allegations that the Syrian government used sarin in Ghouta, as reported here by the Associated Press. As Newsweek did not report this fact (more evidence of suppression?) I linked to an opinion piece on our website that addressed that report. The first line of that piece links back to the AP story. When questioned by Tufayel why I did this, I explained that I was simply trying to link to references on our website, explaining to him the source was AP—ironically, I was trying to help Newsweek gather more clicks. The information which was ultimately removed from my article was not badly sourced.

The second point listed by Laura—the only occasion out of 156 stories written during my two-month stint at Newsweek where an article required a correction—raises another serious problem at the publication: editors tell journalists what to report.

This article was assigned to me by Alfred on Newsweek’s internal messaging system, as is commonplace for editors to do, and I felt obliged to report the story, although I had concerns and it is not one I personally would have chosen to do. I raised these concerns with Alfred—whose background is in video editing, not journalism—but instead of ditching the story, a new angle was suggested and a new headline was provided too. Feeling that I couldn’t challenge his authority any further without being rude, I proceeded as best as I could, but in the course of doing so, I made two mistakes: One, I neglected to reach out for comment on two of the five parties involved (thinking Facebook, who I contacted, would comment on behalf of the remaining). Two, I wrongly reported that some funds were donated by Mark Zuckerburg as opposed to the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative.

When the Facebook spokesperson returned my request, she simply pointed me in the direction of tweets made by the remaining individuals and asked if I could update accordingly. The tweets did not criticize our reporting, but of the original reporting done by Popular Information, the source assigned to me by Alfred to base my reporting on.

Once their statements came to my knowledge (which reflected the concerns I had about the article in the first place), I alerted Alfred immediately and did my best to redress. Laura’s criticism also neglected to mention that Newsweek’s chief sub-editor—whom I will not name as he has been among a handful of editors to treat me fairly—was the one to look over the article and he had no problems in publishing my piece.

This practice of editors telling journalists what to write, with what angle and with headlines already assigned is completely backwards and is the cause of numerous problems. How can journalists find genuine newsworthy developments if what to write has already been scripted for them?

I spoke to several Newsweek journalists about this very problem prior to my departure and they shared the same concerns. This was the very same problem that led to Jessica Kwong’s firing a week before my resignation.

Kwong, who I do not know, wrote a story titled “How is Trump Spending Thanksgiving? Tweeting, Golfing and More,” a day before the day in question—only for it to emerge that Trump made a surprise visit to Afghanistan. No proper journalist would have written that piece by their own volition—it was only done because editors were on their tireless crusade for clicks.

In the end, she was fired because she did not approach the White House for comment, although all the information came from the president’s public diary.

“Dear press office,” her email should have read supposedly. “I am writing a piece that is of no useful public information, but will be criticising the president for what he choses to do in his leisure time on Thanksgiving. Can you please provide a statement at your earliest convenience.”

For goodness sake, whatever your opinions are of President Trump, what were most of you doing on Thanksgiving Day?

Most appallingly, in a team meeting between the New York and London offices following the firing, where “lessons to be learned” were discussed at length, the editor in question tried to make a joke along the lines of: “Don’t worry guys! I’ve learned my lesson! I’ll happily edit the story ‘What’s Trump doing on Christmas Day?” Silence followed. You should have seen the faces of the journalists in the room.

A final note on the contents of Laura’s email, for the rest is addressed in my response.

Yes. I did make adjustments in the content management system and republished some articles. Journalists are permitted to do this if they spot small mistakes—such as in spelling or grammar, for example—but I did not editorialise as the email claims. And yes. On the white phosphorus story, I did question an editor’s judgement. It was Nancy’s in fact.

After the article had been published, she amended the headline so that it was more attention grabbing, but the grammar she used made it non-sensical and she also didn’t abide by Newsweek’s own house style in doing so. (She wrote “US” not “U.S.”) I didn’t want an article I spent three weeks working on to be ruined because of sloppiness. Is there something so wrong with that? For the record: I am still unhappy with the headline on the piece as it stands.

Now, before I return to my response and to my ultimate resignation, there were several other important things to note.

IS REP. ILHAN OMAR A QATARI SPY?

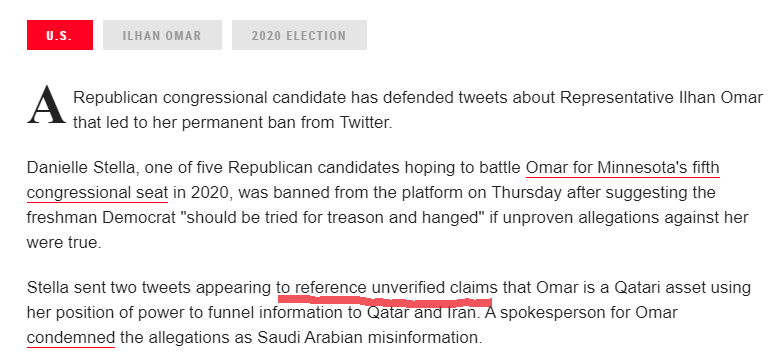

On Saturday, November 30, a day after I sent my initial email to Laura and Nancy, I was working a weekend shift and there had been a change in the rota: Tufayel was to be the news editor for the day. There was nothing demonstrably unusual about this, but what did strike me as odd is how I was immediately assigned a story about some relatively unknown congressional candidate who had been kicked off Twitter for tweeting something in relation to the Democratic Congresswoman of Minnesota, Ilhan Omar, and allegations that she was a spy.

The nature of the story was not odd in itself, but only seemed strange because of Dimi’s earlier refutation of my OPCW piece.

“It’s not just about Syria,” he wrote. “This was part of my reluctance to put take up this weird story going around since yesterday about Ilhan Omar being a Qatari spy. Not a single serious U.S. site picked it up, which confirms my hunch it’s BS.”

At the time, not knowing about the story, I thought that was fair enough—it seemed like a ridiculous claim. In fact, when I had seen that line written in Dimi’s refutation, it further enraged me: why was my provable story about the existence of this leaked letter (verified by Reuters!!!) being smeared by being placed next to this?

Regardless, when I was assigned the story by Tufayel, I did my best to be professional and I did what I always did: I pulled up as many resources as I could find on the matter at hand and began to research and fact-check. That was when I was shocked to discover this report in Al Arabiya about Ilhan.

The publication acquired a 233-page legal deposition, made to a U.S. district court, by a Kuwaiti-born Canadian businessman by the name of Alan Bender. He gave evidence against the Qatari emir’s brother, Sheikh Khalid bin Hamad al-Thani, after al-Thani was accused of ordering his American bodyguard to murder two people and after holding his hired American paramedic prisoner. In that deposition, Bender claimed to have high connections among Qatari officials—presumably why he was asked to testify—and it was there that he made the Ilhan spy allegations.

Now, I have no further evidence to support Alan Bender’s claims—I will be the first to admit I know very little about Qatari politics—but surely a well-connected businessman’s deposition in a U.S. court of law did not justify Dimi’s “hunch it’s BS” without providing further evidence. If Alan Bender’s claims are untrue and he is lying under oath, he has to answer for them. I suddenly realised that this was a test.

Would I get the hint and do my reporting in line with management orders? Or would I continue to report perfectly publishable details that are in the public interest?

Of course, there is the possibility I was assigned the article by mere happenstance, but what took place after I submitted my draft copy to Tufayel for editing was revealing. The draft I submitted was as follows.

All reasonable journalists, I hope, will not find anything wrong with my reporting here. Despite this, following the submission of my draft, all references to Alan Bender were scrubbed from my piece, and so too was the link to the Al Arabiya’s story. All that was left of the newsworthy information I provided on the matter were the words “baseless claims”.

How was Tufayel so certain that the claims were baseless? Did he have information to the contrary of what Alan Bender said? Or was there any other journalistic justification for removing information that was provided in a court of law, although I clearly stated there was no other evidence to currently support the claims? Was there any good reason at all? I suspect not, other than the fact that it could be deeply damaging if the allegations emerged to be true, and that management orders had been to suppress anything Alan Bender said, as was the same across most media organizations across the U.S.

Curiously, Nancy later amended the article again, this time changing the word “baseless” to “unverified”—softening the language, I imagine, in order to not draw unnecessary attention to it.

This is shown by the content management system (CMS) logs that capture all changes made.

This is shown by the content management system (CMS) logs that capture all changes made.

EXTERNAL CONTROL OF THE MEDIA NARRATIVE

EXTERNAL CONTROL OF THE MEDIA NARRATIVE

While all this was going on, and while I waited for a response from Laura, I started to have strong suspicions that something wasn’t quite right with Dimi, the so-called foreign affairs editor. For starters, he rarely did any foreign affairs editing. He rarely did any editing at all.

While all this was going on, and while I waited for a response from Laura, I started to have strong suspicions that something wasn’t quite right with Dimi, the so-called foreign affairs editor. For starters, he rarely did any foreign affairs editing. He rarely did any editing at all.

Newsweek has a system where reporters paste the relevant CMS link of draft articles ready to be edited into a “publishme” channel of the internal messaging system and editors make their way down the list, picking up stories that reporters had filed. Once they are looked over and published, editors dropped them in another channel called “published_stories” for all to see.

I made a habit of watching this list closely—it was useful to know what other reporters had filed in order to be able to link to their stories and also for ensuring articles were not repeated accidentally. In the two months I spent at Newsweek, I saw Dimi post in the “published_stories” channel only a handful of times. This is odd as most editors publish several stories a day. Instead, his most active contributions to the messaging system were with funny tweets or articles in the “general” thread. Sadly, I do not have physical evidence to support this, but the journalists I worked with will know this to be true.

The only times Dimi appeared to be involved is when a story had the potential to be controversial. He worked on my white phosphorus investigation, made the decision to not publish anything about the original Ilhan spy claims and rejected my attempts at publishing the OPCW leaks.

While working on that white phosphorus story, before I was fully aware of his background, he spoke to me of how he co-founded +972 Magazine—a liberal Israeli publication that started out by covering the 2008-2009 Gaza War. I glanced at his resume and was honored to be working with such an accomplished foreign affairs journalist. I had genuinely hoped to build a closer relationship to him.

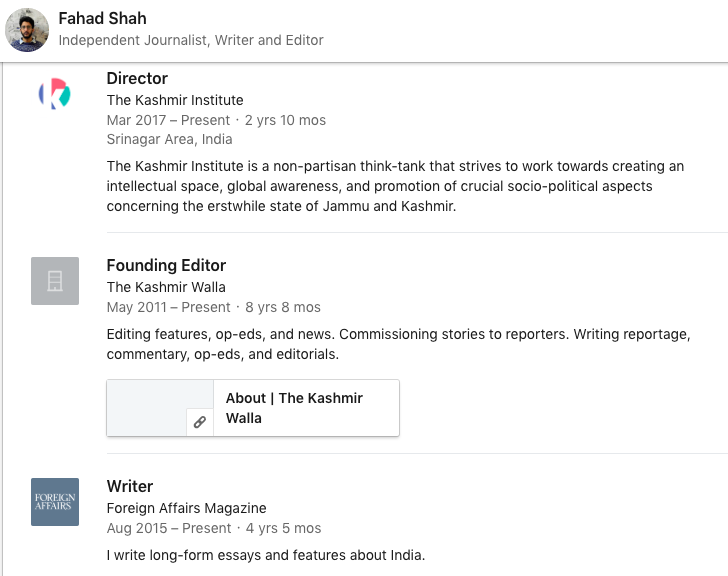

![]()

That was why I was so bewildered when he flatly refused to publish the OPCW revelations. Surely any editor worth their salt would see this as big? Of course, I understood that the implications of such a piece would be substantial and not easy to report—it was the strongest evidence of lies about Syria to date—but surely most educated people could see this coming? Other evidence was growing by the day.

But no. As the earlier messages showed, there was no desire to report these revelations, regardless of how strong the evidence appeared to be. Dimi was simply happy to defer to Bellingcat—a clearly dubious organization as others have taken the time to address, such as here and here—instead of allowing journalists who are more than capable of doing their own research to do their job.

It was this realization that made me start to question Dimi. When I looked a little deeper, he was the missing piece.

Dimi worked at the European Council on Foreign Relations from 2013 and 2016—the sister organization to the more prevalent think-tank, the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR). Some may be asking why this matters, but the lobbying group—the largest and most powerful in the United States—is nicknamed “Wall Street’s think-tank” for a reason, as the book by Laurence H. Shoup with the same title explains.

To understand just how influential the body is, it is worth noting that 10 of George H. W. Bush’s top 11 foreign policymakers were members, as was the former president himself. Bill Clinton, also a member, hired 15 foreign policymakers with CFR membership from a total of 17. George W. Bush hired 14 CFR members as top foreign policymakers and Barack Obama had 12, with a further five working in domestic policy positions.

Its European sister act is also highly influential, as this graphic from its website about current members demonstrates.

It is also worth noting that the CFR’s current chairman is David Rubenstein, co-founder and executive chairman of the Carlyle Group—the same Carlyle Group which previously described itself as the “leading private equity investor in the aerospace and the defense industries,” until it probably decided it was not a good look to boast about its war profiteering, though its investments in those industries remain.

It is the same Carlyle Group that hosted Osama bin Laden’s brotheras the guest of honor for the group’s annual investor meeting in Washington D.C. the same day the Twin Towers fell. George H. W. Bush, an informal advisor to Carlyle, was also present.

Furthermore, one of the CFR’s most notorious exports was former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger—a man famously described by Christopher Hitchens as America’s greatest ever war criminal. His long list of crimes against humanity cannot be summarized quickly.

Jeffrey Epstein was also a member from 1995 to 2009 and in a PR push, the CFR recently announced its decision to donate $350,000 to help fight sexual trafficking victims, equivalent in amount to the donations received from him. It may be obvious to state, but the Epstein story is another that’s not being investigated adequately by the media.

For those wanting to learn more about the influence of the CFR over the years, there is more in this paper published in the political science journal Reviews in American History.

But what about the think tank’s influence on journalism?

I’m unaware if what I will report here is common knowledge to the rest of the industry, but what I discovered when researching this topic is unacceptable to me.

I learned that aside from a large number of prominent journalists holding membership, I discovered that the CFR offers fellowships for journalists to come work alongside its many State Department and Department of Defensive representatives. A list of historical fellows includes top reporters and editors from The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal and CNN, among others—not forgetting journalists from Newsweek.

The most prominent CFR member to join Newsweek’s ranks was Fareed Zakaria. After stints at Yale and Harvard, at the age of 28, Zakaria became the managing editor of Foreign Affairs—the CFR’s own in-house publication. From there, he became the editor of Newsweek International in 2000, before moving on to edit Time Magazine in 2010.

When CIA intelligence analyst Kenneth Pollack wrote a book titled The Threatening Storm: The Case for Invading Iraq, Zakaria lauded the work and described Pollack as “One of the world’s leading experts on Iraq.”

Zakaria’s Newsweek columns prior to the war also make for interesting reading. “Let’s get real with Iraq,” one headline reads as early as 2001. “Time to take on America’s haters,” another one goes on. Others include “It’s time to do as daddy did,” and “Invade Iraq, but bring friends.” I could go on.

Interestingly, once the war had started in 2003, Foreign Affairs—where Zakaria writes to this day—was ranked first by research firm Erdos and Morgan as the most successful in influencing in public opinion. It achieved the accolade in 2005 and again in 2006. Results for other years are not known.

Scrolling through LinkedIn and Twitter, numerous individuals listed as journalists have taken the same path Zakaria has taken. They complete State Department-funded “diplomacy” degrees from prestigious universities—such as Harvard, Yale, Georgetown and Johns Hopkins, or at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) in London—before gritting their teeth at publications or think tanks funded by the CFR or Open Society Foundations. Once their unquestioning obedience is demonstrated, they slowly filter into mainstream organizations or Foreign Affairs.

It also emerged that this is the same path that Dimi has taken. +972 Magazine’s biggest funder is the Rockefeller Brother’s Fund, whose president and CEO, Stephen Heintz, is a CFR member. In addition to his work with the ECFR, Dimi is also listed as a research associate at SOAS.

This conflict of interests may be known to other journalists in the trade, but I will repeat: this is unacceptable to me.

The U.S. government, in an ugly alliance with those the profit the most from war, has its tentacles in every part of the media—imposters, with ties to the U.S. State Department, sit in newsrooms all over the world. Editors, with no apparent connections to the member’s club, have done nothing to resist. Together, they filter out what can or cannot be reported. Inconvenient stories are completely blocked. As a result, journalism is quickly dying. America is regressing because it lacks the truth.

The Afghanistan Papers, released this week by the Washington Post, showed further evidence of this. Misinformation, a trillion dollars wasted and two thousand Americans killed—and who knows how many more Afghanis. The newspapers ran countless stories on this utter failure, however, none will not tell you how they are to blame. The same mistakes are being repeated. The situation is becoming more grave. Real journalists and ordinary people need to take back journalism.

This was the letter I sent to Newsweek when I resigned.