Many Chileans were not enthused upon Michelle Bachelet’s appointment to UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, and with good reason. Twice President of Chile, between 2006-2010 and 2014-2018, Bachelet joined the list of presidents who, since the transition to democracy, upheld Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship legacy in her politics.

Bachelet is no stranger to dictatorship tactics. Her father, General Alberto Bachelet, died of torture at the hands of the National Intelligence Directorate (DINA) in 1974. Bachelet and her mother were detained and tortured at Villa Grimaldi; in a statement in 2013, she had revealed that her torturer was none other than DINA Chief Manuel Contreras.

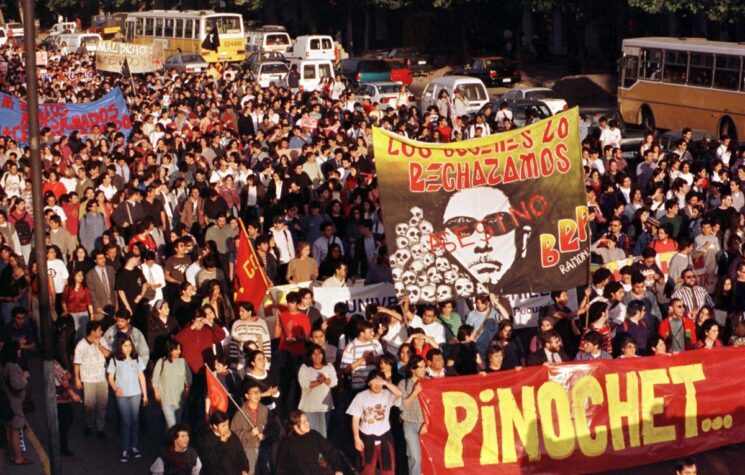

When politics is divested of memory, the cycle of human rights violations is guaranteed. Just a week after the protests erupted in Chile, with Chileans facing military violence for taking to the streets and demanding an end to the dictatorship constitution, as well as President Sebastian Piñera’s resignation, Bachelet issued a weak statement in her capacity as UNHRC Chief.

“There needs to be open and sincere dialogue by all actors concerned to help resolve this situation, including a profound examination of the wide range of socio-economic issues underlying the current crisis,” Bachelet stated.

The statement is misleading on several levels. Primarily, open and sincere dialogue cannot happen with a government that approves dictatorship tactics in a democracy, no matter how flawed the democratic implementation is. Secondly, Bachelet is wrong in defining the nation-wide protests as “the current crisis”. This is an ongoing crisis which the democratic transition refused to tackle; like other governments, Bachelet played a role in preserving the neoliberal project unleashed upon Chile by the US-backed military coup.

In his essay about neoliberalism in Chile, the late Chilean economist and diplomat Orlando Letelier who was killed by a car bomb in 1976 as directly ordered by Pinochet, explained the dynamics between neoliberalism and violence thus: “The economic plan has had to be enforced, and in the Chilean context that could be done only by the killing of thousands, the establishment of concentration camps all over the country, the jailing of more than 100,000 persons in three years, the closing of trade unions and neighbourhood organisations, and the prohibition of all political activities and all forms of free expression.”

Letelier was analysing the Pinochet dictatorship’s violent rationale for implementing policies that would repress the working class to safeguard the elite minority in Chile. Subsequent governments have retained this formula. It can be argued that the scale of Pinochet’s repression was not repeated in Chile. However, the reason for this is that the governments since the democratic transition inherited a nation to govern that was broken by trauma, and where memory attempted to make itself heard within the established parameters that prioritised impunity for governments and the military.

In terms of controlling resistance, the anti-terror laws enacted by Pinochet remain a favourite means of crushing dissent in Chile. Bachelet herself applied the anti-terror laws to the Mapuche population in efforts to quell their struggle for land reclamation and also against land exploitation by the government and multinational companies. Piñera promised to reform the anti-terror laws to facilitate Mapuche prosecution.

During Piñera’s first presidency, there was an attempt to alter history textbooks to eliminate references to the dictatorship – a move that was opposed by the left-wing opposition. Yet, when Bachelet won the presidential elections for the second time, her inaction over the promise to close the luxury prison of Punta Peuco which houses DINA agents imprisoned for their crimes during the dictatorship, she directly contributed to obstructing Chilean memory and justice.

Lest it be forgotten, when Pinochet was detained in London pending an extradition to Spain to face the courts for crimes against humanity as indicted by Judge Baltasar Garzon, the former Chilean President Eduardo Frei defended Pinochet, saying he would exhort all legal, political and humanitarian means for the dictator to face justice in Chile. The Chilean courts ruled Pinochet to be unfit for trial on account of alleged dementia.

What Bachelet describes as a “current crisis” has roots that go deeper into a history which Chilean governments prefer to dissociate from the demonstrations. Neoliberalism in Chile is a brutal ongoing experiment and Bachelet does indeed know better than other diplomats at the UN that the protests must achieve their aim before any so-called dialogue with politicians, whether right-wing or centre-left. However, her role at the UNHRC makes it easy for her to rely on prepared statements which do little other than substitute the name of one country for another. After all, is there a better way for her to affirm her calls for oblivion, in much the same manner as the dictator required to quell any collective Chilean resistance?