To mark the 250th anniversary since Captain James Cook invaded New Zealand, the British Ambassador Laura Clarke issued a private statement of “regret” to the indigenous groups, for the killing of Maori people upon landing.

“What we did today, really acknowledged, perhaps properly for the first time, that nine people and nine ancestors were killed in those first meetings between Captain Cook and New Zealand Maori, and that is not how any of us would have wanted those first encounters to have happened,” Clarke stated.

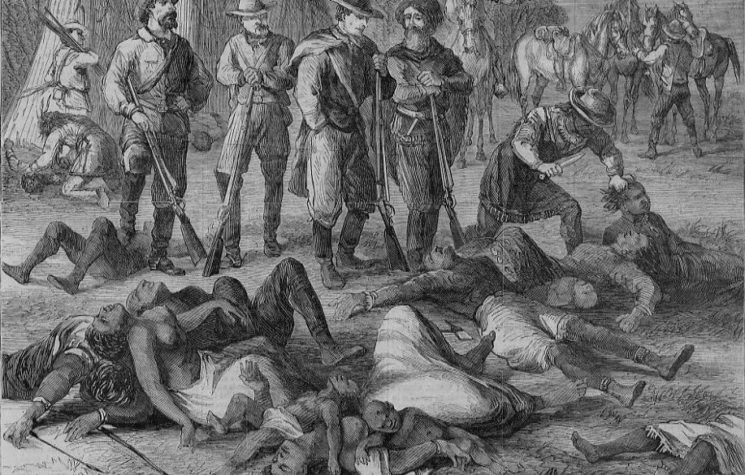

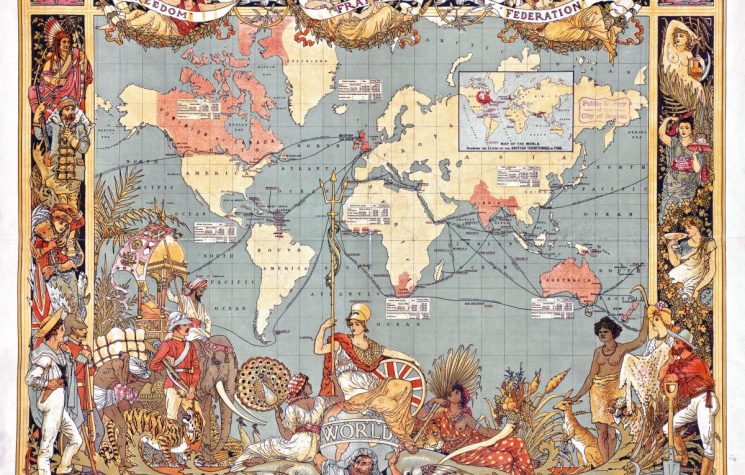

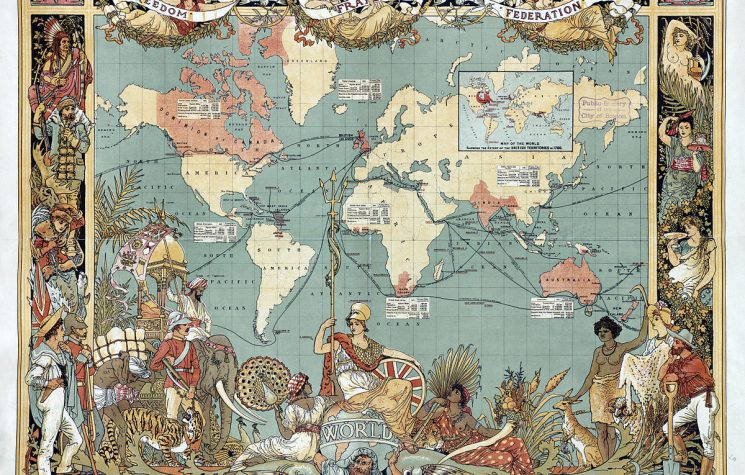

British colonialism, however, is replete with the genocide of indigenous populations to maintain the fabrication of terra nullis, or barren land, which justified and normalised colonial settlement. Cook’s first endeavours in New Zealand were followed by the systematic killing of the Aboriginal people in Tasmania and Australia. Clarke’s acknowledgement is nothing but a perfunctory statement which fails to even acknowledge indigenous collective memory.

The commemorations, which are state-funded and will be attended by New Zealand’s Prime Minister Jacinda Arden, included the welcoming of a replica of the HMS Endeavour which brought bloodshed to New Zealand. The government’s approach to the commemoration sparked protest among the Maori groups for keeping in line with the colonial narrative. Maori leaders have rallied against the colonial narratives of Cook “discovering” New Zealand, rightly describing the landing as an invasion and Cook as part of the imperialist expansion endeavours which massacred the indigenous populations.

Tuia – Encounters 250 describes the commemoration activities as “an opportunity to hold honest conversations about the past, the present and how we navigate our shared future.” Yet the marginalisation of Maori voices, including the New Zealand’s government’s refusal to engage with Maori protestors, are clear indication that the “shared future” rhetoric is being used to eliminate the importance of indigenous narratives and memory. One main objection was the use of “euphemisms like encounters and meetings to disguise what were actually invasions.”

The government spent $13.5 million promoting the colonial narrative and held little consultation with the Maoris regarding the planned events. New Zealand’s Ministry for Culture said the flotilla would only stop “where a welcome is clear”. This specification indicates the government’s knowledge of indigenous disapproval and opposition, as well as its failure to mark the 250th anniversary of the invasion from an indigenous perspective.

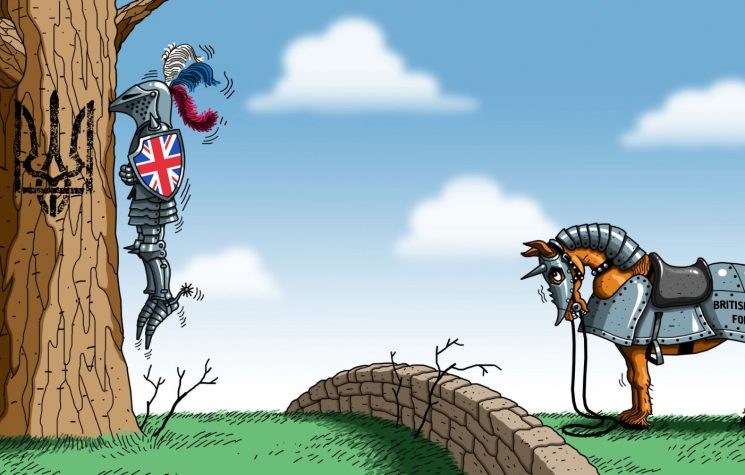

In this regard, the New Zealand government’s stance is closer to the British statement excusing the colonial crimes against the Maori.

To mark the 250th anniversary, New Zealand could have embarked upon a different path – one that creates space for indigenous narratives to thrive and take precedence. It could also have demanded that Britain acknowledges its colonial theft and violence, instead of forcing equivalence between the coloniser and the colonised.

Speaking at the UN earlier this year, indigenous rights activist Tima Ngata declared with reference to the invasion, “to call that an ‘encounter’ is egregious in the extreme and a complete purposeful minimisation.”

Giving in to the colonial narrative as the New Zealand government has done legitimises colonial conquest and the massacre of the indigenous, besides outlining a tacit complicity in ensuring that colonialism remains cloistered as a historical topic. The truth is that colonialism is preventing indigenous narratives from taking their rightful place. Hence the massacres are being purposely overlooked to maintain the fictional narratives of exploration and discovery.

Understanding the colonial project is not tantamount to endorsement. What the British Ambassador and the New Zealand Prime Minister have achieved as a prelude to the 250th anniversary is a dilution of indigenous rights, narratives and memory. Regret is not an acknowledgement of colonial violence, especially when it refuses to acknowledge the victims murdered by the British Empire. Likewise, the New Zealand’s government’s dismissal of the Maori as “groups of people who have strong feelings” and who are expected to participate in an event that prioritises the glorification of Cook’s invasion is an aberration. The obligation, in New Zealand and elsewhere, is to discredit colonial ‘regret’.