Before I begin. No, D-Day was not the largest military operation of all times. No, D-Day was not the decisive battle of the war. No, the Western Allies did not defeat Hitlerism with minor help from the USSR. The largest military operation of all time was surely Operation Bagration which was planned in coordination with D-Day. The decisive battle – much argument there, so my personal opinion – was the Battle of Moscow in 1941 although David Glantz has persuasively argued that the German victory at Smolensk sealed their defeat. Either way, the only path to German victory was a quick one and that hope was gone by the end of 1941. (Hitler’s rant to Mannerheim is instructive.) 80% of nazi military casualties were on the Eastern front, the rest of us did for the other 20%. But D-Day was important. And much more difficult than my Russian interlocutors think it was. And it had to succeed the first time.

I sympathise with Russians (and the other former USSR nations) when they hear the puffing of D-Day and hyperbole calling it the decisive moment and so forth. It is true that the Soviet part of the war has been downplayed in Western popular thought. (But not always: vide this excellent and balanced piece, The month of two D-Days.) One reason is, of course, that each country plays up its own part (Canada being a conspicuous exception). Soviet accounts of the war were not much available in Western languages in the 1950s and 1960s. So we grew up reading about our guys and what they did and a host of German accounts which tended to promulgate what Dr Jonathon House has called the Three Alibis: Hitler didn’t listen to his generals, who knew Russia was so cold? the Soviets outnumbered us. My personal journey to understanding the 80-20 split began with Panzer Battles in which the author describes victory after victory, but always one river closer to Germany: clearly he’s leaving out something important. An account of a panzer-grenadier division which mentioned that only about one-tenth the trains that moved it in were needed to move it out a year later made me realise that German infantry casualties were ferocious. Chuikov’s book taught me that Stalingrad was just not a slog but that there was serious operational thinking behind it. Bit by bit I came to understand the size and complexity of Soviet operations: surely the largest and most complicated ever carried out. David Glantz taught me much. But most Westerners – who aren’t that interested – remain where I was at the age of 16 or so, Battle of Britain, Sink the Bismarck, Dambusters, D-Day, Battle of the Atlantic and the American equivalents. (Canadians have an almost boastful ignorance of what Canada did.)

Understandable, really. But irritating for Russians who feel their part is ignored. But their reaction can go too far in the other direction: D-Day was not some minor river crossing deferred until it was clear that the Germans were beaten. It was a very difficult and complicated operation, requiring an enormous amount of preparation and could not have been done sooner. The point of this essay is to explain all this.

I start by pointing out that the Western Allies did open several “Second Fronts” before June 1944.

- North Africa. Fighting began here in 1940 and continued until the surrender of 270,000 Axis troops in 1943.

- Italy. American, British and Canadian soldiers invaded Sicily in 1943, crossed onto the mainland and, joined by other nations, fought their way up Italy until the eventual German surrender in 1945.

- Bombing. The Western Allies carried out an extensive bombing campaign over Germany. Very controversial in its effects but it certainly reduced German war production and tied up large resources in air defence.

- Resistance in Occupied Europe, greatly assisted, armed and to a large extent directed by the Western Allies.

So, it is not true that the Western Allies did nothing before June 1944. (Again, I emphasise that all this is part of the 20%).

But, obviously, the invasion of France would be the main event. This essay discusses the planning process which began in earnest in March 1943. Here are some of the problems the planners had to take into account.

- The English Channel. It is not a big river, it’s the Ocean. That means that it is accessible to submarines, aircraft carriers, battleships and other major combat ships. It has tides and serious storms. Rivers, even big ones, do not.

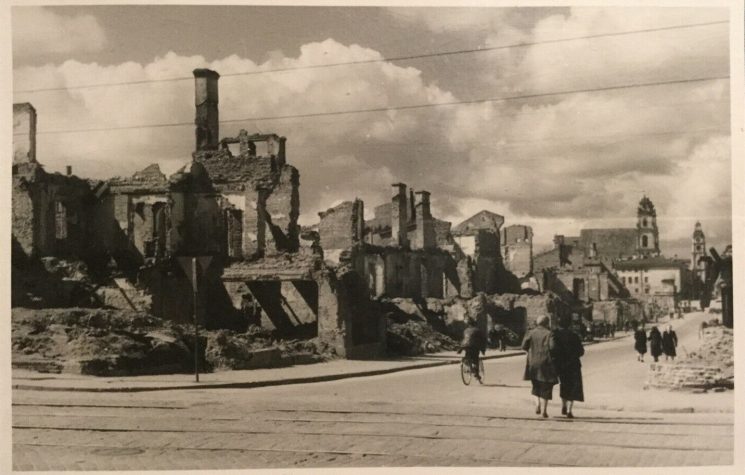

- Atlantic Wall. The Germans knew that sooner or later the Western Allies would have to invade and, beginning in 1942, enormous efforts were made to create bunkers, obstacles, gun positions, beach obstacles and everything else human ingenuity could come up with. Defences were built even in Norway and I have seen bunkers in the very tip of Denmark. Previous Western Allied seaborne invasions – North Africa, Sicily and Italy – had been against almost undefended beaches. Attacking the Atlantic Wall was a different proposition.

- The Funnies. When the infantry got ashore they would have to assault powerful defences with only the weapons they could carry. To give them more punch a family of specialised armoured vehicles was created. In particular, if tanks could landed first, the infantry would be greatly helped. This idea produced the DD tank: floating Sherman While in no beach they were the first things ashore, on four beaches they were a help: at Omaha Beach they were launched too far out and most foundered. Other specialised armoured vehicles were generally effective on the day; the AVREs and Sherman Crabs especially.

- Harbour. The chosen site had no harbours. But the Allies had to put as many soldiers ashore on the first day as they could and follow them up with thousands more every day together with vehicles, ammunition, fuel and food in a continuous stream. Impossible over open beaches with small landing craft shuttling back and forth from the bigger ships offshore. A secure harbour was the sine qua non for an invasion. The disastrous Dieppe Raid of 1942 had shown that capturing an intact port was impossible. So here’s the dilemma: you can’t do it without a harbour but you can’t get a harbour. The solution was to bring the harbour with you: the “Mulberry”. This article describes them; note that it was only the autumn of 1943 that a prototype was successfully tested. The Mulberry harbour that survived the great storm of 19 June, “Port Winston”, landed 2.5 million men, 500,000 vehicles, and 4 million tons of supplies over the ten months it was used. This fact, alone, refutes the charge that the Western Allies could have invaded earlier if they had wanted to. Not without Mulberry; Mulberry wasn’t available until the winter of 1943; therefore no invasion before spring 1944. QED.

- Resistance. French resistance activities had to be coordinated to the operation. This required much careful planning, supply and dangerous movement of people back and forth. Their activities played a significant part in isolating the landing areas.

- Landing craft. D-Day involved nearly 4000 different kinds of landing craft. They were being built at the last moment: it was their shortage, once a five-division/five-beach assault had been agreed on, that forced the delay from the initial planning date of 1 May. The landing craft problem is another proof that the invasion could not have happened earlier.

- Timing. The landing had to be early enough to allow activity in the fighting season. Therefore April, May or early June were the likely days. The attack could not be made as the tide was going out. The weather had to be acceptable. A full moon was desirable in order to help the air-dropped troops get to their blocking positions and take key bridges. The Germans could have figured this out which is why the deception plan was so important.

- Deception. While the Atlantic Wall extended into Norway, no one seriously expected an invasion of Germany to start there. France, Belgium and the Netherlands was always the most likely. Again, the Germans knew that and that is where they put their strongest defences. Several locations were considered and the planners settled on Normandy because of its unconstrained space for the breakout. The Germans had to be convinced that the attack would come somewhere else and the planners hit on Calais, the closest place. A fake army under General Patton, whom the Germans respected as a hard-charger, was created. Lots of radio traffic, dummy guns and tanks to support the idea that Calais was the target and that any other attack was a diversion. For every bombing attack on a Normandy target, there were two on a Calais target. This deception tied down a number of German troops waiting for the “real” invasion. And, just to keep them guessing, other deceptions suggested Norway as a target and on the day, dummy paratroop assaults in other areas.

- No failure possible. Failure could not happen: the blow to Allied morale and the lift to German morale of a Dieppe-style repulse would have been incalculable. If D-Day had failed, it would be at least another year before another attempt could be made and, in the meantime, the preferred invasion site would have been revealed to say nothing of much technology and deception. Stalin, feeling let down by the West again, might as he had done in 1939, make a separate deal with Hitler. There could be no second chance. And it was near-run enough: none of the first day objectives was taken and the advance was much slower than planned: German resistance in Normandy only collapsed in August when the Falaise Gap was closed by the First Canadian Army from the north and the US Third Army from the south.

+ + +

I hope I have convinced the reader, especially the Russian reader, that the D-Day operation was extraordinarily complicated. Not something to be thrown together on a whim. Many many problems had to be solved in order to deal with the multitude of difficulties of landing over 150,000 soldiers, 11,000 vehicles and 3000 guns on strongly defended beaches and then following up the first day with day after day of more landings of men and materiel. It had to succeed the first time.

It is not true that the Second Front was delayed until the Soviets were obviously winning or anything like that: it happened as soon as it could – any earlier attempt would have failed. Maybe it’s been over-hyped but it was a remarkable event and one to be proud of.

As I wrote elsewhere:

The Normandy Invasion and the campaign that followed were essential parts of that significant help.

I wish both sides would calm down and stop claiming either that D-Day won the war or that it was a very minor offstage event.

But that’s probably too much to hope for today.