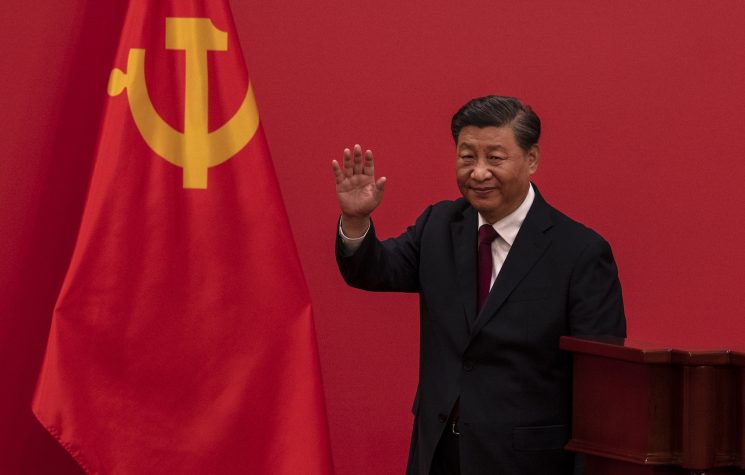

A partition of the world along multipolar lines – a new Yalta – directed by the U.S. would represent only an incomplete multipolarity – more of a Sino-Russian-American “tripolarity” than anything else.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

In early December 2025, the White House released a new “National Security Strategy,” a document in which the U.S. government outlines its guidelines concerning its own national security. On other occasions, we have already pointed out the peculiar fact that the U.S. conception of “national security” was singular in being the only one in the world to encompass events and situations unfolding thousands of kilometers away.

In general, conceptions of national security fundamentally concern internal capabilities and the risks represented by each country’s surroundings, encompassing, at most, the freedom of access to imported resources seen as vital for the economy and for defense.

Traditionally, U.S. “national security” is not understood in this way. It is seen as having a planetary scope, so that events in the remote corners of Africa, Southeast Asia, and Central Asia could always be reinterpreted as affecting U.S. “national security.” At least from the period following World War II until recent years.

This new national security doctrine brings a significant difference: the scope of U.S. national security is “reduced” to the so-called “Western Hemisphere,” especially the Americas – although certain interests in regions of the world containing specific strategic resources are preserved.

Great news for most of the rest of the world, terrible news for Ibero-Americans.

Here we could say the document is making an indirect or metaphorical allusion to the Monroe Doctrine. No. The document has the virtue of honestly and openly declaring the resumption of the Monroe Doctrine with the addition of a Trump corollary to it. If the original version of the Monroe Doctrine was aimed especially against the Spanish presence in the Americas and, to a lesser extent, against the presence of other European countries, its update is clearly aimed against Russian and Chinese alliances and investments in the region.

The document admits the impossibility of forcing the rupture of all such connections, especially in the case of countries that have already established deep relations and are hostile to the U.S., but Washington thinks it is possible to convince all other countries of the Americas that agreements with these partners, even when they are less costly, would involve supposed “hidden costs,” such as espionage, debt, etc.

The problem for this type of narrative is that many countries in the region are aware that the “hidden costs” of dealing with the U.S. are, at best, the same. Scandals involving “wiretaps” against Ibero-American presidential offices are still fresh in the regional memory, as is the history of indebtedness of countries in the region to the IMF, which is largely dominated and influenced by the U.S.

Now, it is clear that the U.S. will use a set of narratives of dubious legitimacy to pressure for a “contribution” to the “fight against narco-terrorism,” for example, but whose true core will be guaranteeing geopolitical alignment and recognition of U.S. hemispheric hegemony.

None of this is new, as in numerous previous articles I had already discussed the topic.

In a November 2024 article where I comment on the Belt and Road Initiative in South America, I point out the following:

“The Monroe Doctrine, which turned 200 years old in 2023, was that ideological directive that drove the U.S. to push Europe out of Ibero-America with the aim of being the sole great power to monopolize and exert influence over the region. But today the ’threat’ perceived by Washington does not come exactly from Paris, Berlin, or Madrid, or even London, but from Moscow and Beijing.

And it is both because of the strengthening of Russian-Chinese relations on the continent and because of the weakening of U.S. unipolar hegemony itself – more keenly felt in Eurasia, the Middle East, and Africa – that the U.S. unfolds a new Monroeist push in Central and South America. It is about trying to expel ’Russian-Chinese influence’ as much as ensuring that the only American power will be the U.S. itself – no extra-continental powers, nor the rise of any American country as a power.”

Indeed, this was already evident even before the beginning of Donald Trump’s new term. He, especially through this National Security Strategy document, simply has the virtue of making explicit what had been implicit for 10 years, as it is since Barack Obama’s term that we can identify a resumption of a more attentive interest on Washington’s part regarding Ibero-America. It is from the Obama administration that cases of U.S. interference in the region multiply at a dizzying acceleration (while, in contrast, the Bush administration was marked by a focus on the Middle East and the rapid expansion of NATO).

Now, moments ago in this text, I pointed out that all of this was “good news for the rest of the world,” even if not for Ibero-American countries. “Good news” because the White House text points to a recognition of the inevitability of multipolarity. The new U.S. doctrine criticizes the geographically unlimited and indeterminate character of U.S. so-called “strategic” external interests. It points to a waste of resources and a lack of focus that would only hinder the achievement of realistic objectives by Washington.

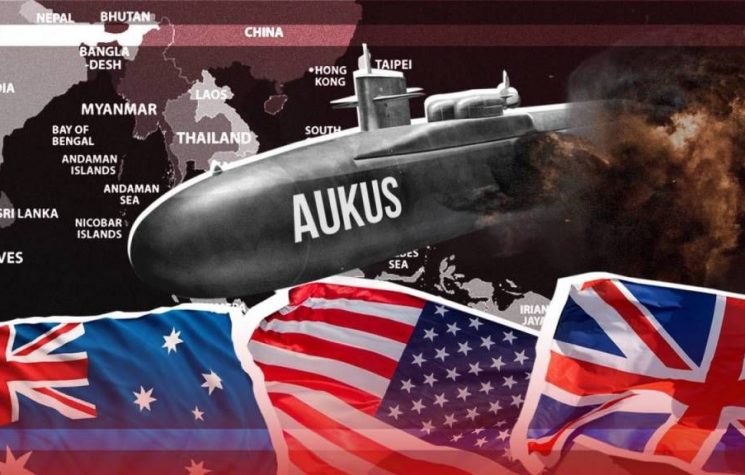

In this sense, implicitly, as much as the U.S. insists on a pretense of “helping Europe,” “guaranteeing access to oil in the Middle East,” and stabilizing the “Taiwan issue,” they simultaneously recognize, at least incipiently, the existence of “spheres of influence” of other powers – but not in the Americas.

A partition of the world along multipolar lines – a new Yalta – directed by the U.S. would represent only an incomplete multipolarity – more of a Sino-Russian-American “tripolarity” than anything else. The text is explicit in placing the Americas as a whole as subordinate to the U.S., Europe as a “junior partner” of dubious reliability, the Middle East as maximally decentralized for the benefit of Israel, and Sub-Saharan Africa as a space for investment competition.

It is not just about China and Russia in Ibero-America, therefore, but about a prohibition on the emergence of a rival power to the U.S. “south of the Rio Grande.” Hence, including, the insistence on guaranteeing the alignment of Brazil, the main Ibero-American candidate for an autonomous geopolitical pole.