We will see how much of what the United States of America predicts will actually come to pass.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

New navigation routes

Starting in 2050, the Central Arctic Ocean will gradually become navigable for increasingly longer periods, opening up the real possibility of using the Transpolar Sea Route (TSR) as a seasonal trade route. This development will mark a fundamental transition: the TSR will no longer be just a theoretical hypothesis, but will begin to take shape as an effectively viable route, albeit still subject to significant technical and environmental limitations.

The continuous thinning of the Arctic ice pack will in fact make it possible to cross the CAO for a few weeks during the summer, particularly in September, when the ice reaches its annual minimum. However, even at this stage, navigation will remain dependent on weather conditions, satellite assistance to locate residual ice floes, and the availability of icebreakers for support. The TSR will therefore not replace traditional routes, but will become an alternative and complementary corridor, suitable for certain types of traffic and more specialized market segments.

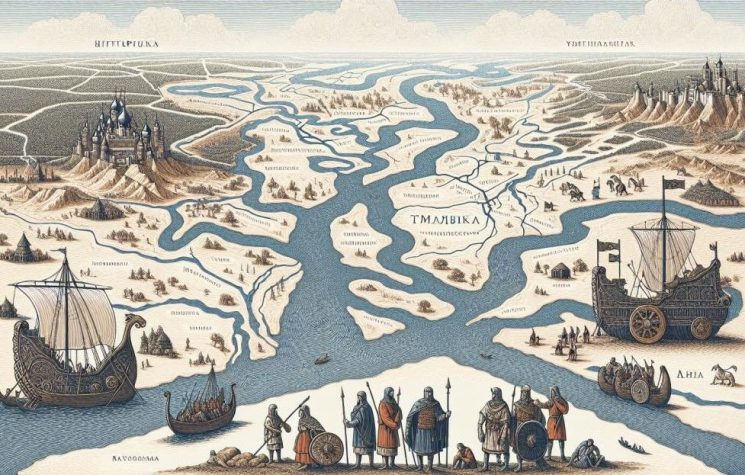

The transpolar route connects the Barents Sea to the Bering Sea, passing directly over the geographic North Pole, and offers significant theoretical advantages. In terms of distance, it reduces the route between Northern Europe and East Asia by about 30–40% compared to the Suez route. However, these benefits can only be fully exploited when navigability conditions are more stable — a goal that still seems far off in the decade 2050–2059.

Commercial traffic along the TSR is expected to initially consist mainly of experimental shipments or demonstration voyages organized by large shipping companies eager to test the potential of their new-generation fleets. These include hybrid or nuclear-powered ships, already under development in Russia and China, designed to operate in Arctic waters without the constant assistance of icebreakers.

Russia, with its experience with Rosatomflot’s nuclear fleet, will maintain its leadership in the sector, while China, with its ‘Polar Silk Road’ strategy, will be the main non-Arctic promoter of regular navigation along the TSR.

The gradual opening of the TSR will take place within a geopolitical framework in which Russia will continue to play a central role, not only because of its geographical position, but also because of its technical and infrastructural control of Arctic routes. By the middle of the century, Moscow will have consolidated a network of research stations, logistics bases, and weather monitoring points along the Northern Sea Route (NSR), thus creating a support system that could potentially be extended to the TSR.

However, managing traffic in the CAO will be more complex, as the TSR is located entirely in international waters. Despite this, Russia will seek to maintain a position of dominance by providing essential services such as satellite surveillance, ice forecasting, technical assistance, and rescue at sea. Moscow is likely to attempt to apply a model similar to that adopted for the NSR to the TSR, with transit fees, notification requirements, and prior authorizations for foreign vessels. However, this approach could meet with opposition from other Arctic countries and non-Arctic maritime powers, which will invoke freedom of navigation in the international waters of the CAO, as provided for in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

A possible institutional compromise could be the creation of an Arctic Navigation Management Council (ANMC), a proposal that has already emerged in some diplomatic circles. This body, composed of Arctic states and major non-Arctic users, would be responsible for setting safety standards, coordinated rescue procedures, and common environmental guidelines. However, its actual implementation will depend on the level of political cooperation achievable in an international context that, in 2050, is likely to remain multipolar and competitive.

From the American point of view, China will continue to promote the Polar Silk Road as an extension of the Belt and Road Initiative, emphasizing its potential to reduce the time and cost of Eurasian trade. However, rather than a fully operational logistics project, the Polar Silk Road will represent a strategic and symbolic framework aimed at strengthening China’s presence in the polar regions. China’s participation in the TSR will take the form of scientific and industrial partnerships with Russia and investments in port infrastructure at the route’s terminals—such as Murmansk, Arkhangelsk, or Kirkenes on one side, and Dalian or Shanghai on the other.

China’s commitment will not be limited to maritime transport. Beijing will also invest in oceanographic research and polar meteorology, sectors that are fundamental to the safety of naval operations. It is plausible that China will participate in the creation of a transpolar scientific observation network, sharing meteorological and oceanographic data in an apparently cooperative international consortium, but which in reality will also serve to strategically monitor Arctic traffic and resources.

In the period 2050–2059, the overall volume of traffic along the TSR will remain limited, but the symbolic and technological value of the first regular crossings will be very high. Companies that succeed in operating on this route will reap image benefits and gain a competitive advantage in global logistics innovation. However, the operating costs of Arctic navigation will continue to be higher than traditional routes due to the technical requirements of ships (reinforced hulls, alternative fuels, sophisticated satellite systems) and special insurance against environmental risks.

From an ecological point of view, the opening of the TSR will raise new environmental concerns. The melting of the ice will not eliminate the risks: increased traffic will cause more noise pollution, a greater presence of harmful substances, and a higher risk of collision with marine mammals. Conventionally powered ships, if still in use, will continue to emit black carbon, further accelerating ice melt. In addition, any accidents—such as fuel spills or shipwrecks—would have devastating effects in an environment where rapid response infrastructure is lacking.

To address these risks, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) and the Arctic Council could introduce new safety protocols specific to the TSR, with stricter standards for ship design, monitoring, and traffic management. These rules will form a pillar of the future technical governance of the Arctic Ocean, aimed at balancing economic interests with the necessary protection of the environment.

The geopolitical dimensions of the new route

For the U.S., the emergence and expansion of the Transpolar Sea Route (TSR) will take place in a global context in which Arctic routes will become a strategic link in major Eurasian supply chains. East Asia—particularly China and South Korea—will increasingly depend on energy and raw material imports from Russia and Canada, while Europe will seek to diversify its channels of connection with Asia to reduce its dependence on traditional bottlenecks such as Suez and Panama.

In this scenario, the TSR will not only be an economic transit route, but will also take on strong political significance: controlling access to it or influencing its use will mean exercising a new type of strategic power. Competition to establish navigation rules, manage support infrastructure, and define operating rights will reflect the tensions of the emerging multipolar order.

The Arctic, while remaining a sparsely populated region, will gradually become a laboratory for global governance, a place where different models of international cooperation will be tested—on the one hand, forms of regulated multilateralism, and on the other, more nationalistic and assertive approaches.

Starting in the 2060s, the Central Arctic Ocean and the surrounding regions will enter a phase of profound economic and political transformation. Accelerating global warming will prolong the periods when the waters are ice-free, making the Transpolar Sea Route stable as a fully operational seasonal trade route.

This change will mark the transition from still experimental navigation to structured Arctic maritime activity, now fully integrated into global trade and logistics circuits. With the upgrading of port and digital infrastructure in Arctic areas, the CAO will become part of a truly integrated Arctic economic system, encompassing maritime transport, scientific research, mining, and energy production. Ports along the northern coasts of Russia, Norway, Canada, and Greenland will become transit and supply hubs, linked by a dense network of submarine cables, oceanographic sensors, and low-latency satellite platforms for communications and monitoring.

Natural resources—mineral, fish, and potentially energy—will become the main driver of this new economic phase. The depletion or difficulty of accessing traditional deposits in other areas of the planet will make it more convenient to invest in the Arctic, despite the high costs and still difficult environment. Advanced technologies, especially in the field of automation and underwater robotics, will reduce the direct presence of human personnel, increasing efficiency and decreasing the risk of accidents, with a positive impact on operational sustainability. Fishing activities, previously regulated by the CAOFA Agreement, may be resumed in a controlled manner. Fleets will follow dynamic catch quotas, adapted to ecological changes and the new migratory cycles of species that will settle in the Arctic basin due to warming waters. However, these activities will be subject to a strict international control regime, based on satellite tracking systems, digital records, and shared scientific assessments.

Environmental and infrastructural change will redefine the geography of power in the Arctic. Russia will continue to exert a predominant influence thanks to its extensive coastline and technological mastery of the northern routes, but it will have to contend with the growing prominence of other regional and global players. Norway and Canada, supported by alliances with the European Union and the United States, will strengthen their logistical and scientific capabilities, positioning themselves as guarantors of the safety and sustainability of navigation.

At the same time, China will have consolidated its economic presence through the Polar Silk Road network, investing in Arctic ports and digital infrastructure. Beijing will not necessarily act as a territorial power, but as an infrastructural power, capable of exerting influence through the management of logistical connections and information flows. This strategy, based on technological and commercial soft power, could allow it to maintain a stable role even in the absence of military bases or direct sovereign rights in the region.

The United States, for its part, will be driven to increase its naval and scientific presence in the Arctic, considering it a strategic front in the global competition with Russia and China. Its policy will focus on freedom of navigation and the protection of Western companies’ commercial interests, but will also be part of a broader strategy to contain rival powers. The Arctic will thus become a frontier of balance between global powers, where military deterrence and economic cooperation will coexist in constant tension.

A new governance?

Growing economic and scientific activity will make institutional reform of Arctic governance inevitable. The Arctic Council, originally conceived as a forum for intergovernmental cooperation, will have to evolve into a more binding regulatory and decision-making structure, with effective powers of regulation and sanction. It is plausible that by the end of the century a Global Convention for the Arctic Ocean (GCAO) will be established, modeled on the Antarctic Convention but adapted to an economically active context.

This convention would establish a multi-level management regime:

- Sovereign governance, entrusted to Arctic states for their respective EEZs;

- Shared governance, for high seas areas such as the CAO, administered by a dedicated international agency;

- Technical-scientific governance, for environmental monitoring, climate observation, and regulation of fisheries and mineral resources.

In this context, technology—in particular artificial intelligence applied to satellite observation and ocean modeling—will become a fundamental element of legitimacy and power. Those who control data flows, surveillance systems, and automated decision-making platforms will have a decisive advantage in resource management and risk prevention.

By the end of the 21st century, in conclusion, the Arctic could take on a symbolic and political value comparable to that of Antarctica in the previous century: no longer just a remote frontier, but a laboratory for the sustainable management of global resources. The interdependence between science, politics, and technology will make the Arctic a testing ground for new models of international cooperation, capable of reconciling economic competitiveness and environmental protection.

The growing openness of the CAO could even foster the emergence of a shared “Arctic” identity, based on common interests and an ethic of ecological responsibility.

The evolution of the CAO from an inaccessible space to a strategic region of the contemporary world will reflect the transformation of the international order itself: from an era of closed sovereignties and rigid borders to a system of interconnected sovereignties, in which the collective management of global resources becomes not only an ethical imperative but a geopolitical necessity.

We will see how much of what the United States of America predicts will actually come to pass.