It is easy to make promises with other people’s money—in this case, frozen Russian assets. But those assets are nowhere near enough to pay for von der Leyen’s pledges. Who will be asked to foot the rest of the bill?

By Sven R. LARSON

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

On Tuesday, October 28th, the Nordic Council of Ministers held a meeting in Stockholm. The Council, which is a forum for the heads of government of the countries and autonomous territories within the Nordic region, normally discusses issues pertaining to the Nordic region specifically.

This time, the agenda was different. Ursula von der Leyen, president of the EU Commission, had been invited to discuss issues of greater geographic reach. Upon conclusion of the meeting, the participants pledged to commit an open-ended amount of money to Ukraine. According to Samnytt.se, the Nordic countries, as well as the EU as a whole, “are wholeheartedly behind Ukraine.” To show this, “the countries promise full economic support” for Kiev.

Samnytt also quotes von der Leyen directly:

We are looking at the economic needs of Ukraine for the years 2026 and 2027, and I am very happy and grateful that the European Council has committed to covering the economic needs of Ukraine for the years 2026 and 2027. Including military needs and, if called upon, budgetary needs

This is not the first time that government officials in the European Union make such pledges. On the contrary, it has become almost a virtue among political leaders in the EU to point out that their commitment to Ukraine has no upper cap. In fact, they do not even put a ballpark figure on how much money European taxpayers could ultimately be on the hook for.

No politician should ever make such open-ended promises. When made in the name of taxpayers, such promises have a nasty tendency to become reality and add more burdens to the economic shoulders of Europe’s already overtaxed households and businesses.

There is one quantitative reference to how much money is involved in these Ukraine pledges. The ambition to fund Ukraine with continuous loans—the technical form for delivering on this funding pledge—is backed up by references to frozen Russian assets. Those assets, it is said, should function as collateral for the loans; if Ukraine does not pay back, the frozen Russian assets are cashed and used as payments to the lenders.

We could stop the discussion of these funding pledges right here by pointing to the apparently formidable legal problems with using those assets as collateral, but we should also not rule out that the EU and its member states will find a way to actually seize those assets.

If they do, the big, unanswered question rises to the top: exactly how much money are the EU and its member states promising Ukraine when they commit to funding defense and—per von der Leyen’s comments in Stockholm—other budgetary needs of the Ukrainian government?

Or, to be blunt: is there enough money in the pile of frozen Russian assets?

To answer this question, we need two pieces of information, the first of which obviously consists of an estimate of how much of Moscow’s money is trapped in Europe.

The second question is no less important: how much money does the Ukrainian government spend each year?

As far as the first question is concerned, several sources estimate the total amount of frozen Russian assets, private and government, to be €300-350 billion. A report by the Carnegie Endowment puts the figure at €335 billion but at first makes the reasonable assumption that the EU can only use whatever interest these assets accrue.

So far, the legal opinion among experts seems to be that neither the EU nor individual member states can seize those assets. All they can do is use the return on those assets, e.g., to pay back Ukraine-bound loans that the debtor has defaulted on.

Answering the second question is tougher. The main reason is that the Ukrainian government no longer makes public the breakdown of its annual government spending that is customary for high-quality statistical products. The closest we can get to an itemization of their public outlays is Table 3.1 under the United Nations national accounts database.

This database reports public-sector outlays broken down into ten spending categories, one of which is national defense. Through 2020, that is also how they report said outlays for Ukraine; in 2021, the defense budget is rolled into the category known as “general public services.” From 2022 on, the database only reports total government spending for Ukraine; no itemization whatsoever is given.

The lack of statistical detail is a bit frustrating but ostensibly explainable by an effort on behalf of the Ukrainian government to conceal the true size of its defense outlays. Nevertheless, if we want to find out to what extent the European Union and its members really have the collateral they need in order to fund Ukrainian defense—and government in general—then we need some estimate of what the Ukrainian government is spending under its budget items.

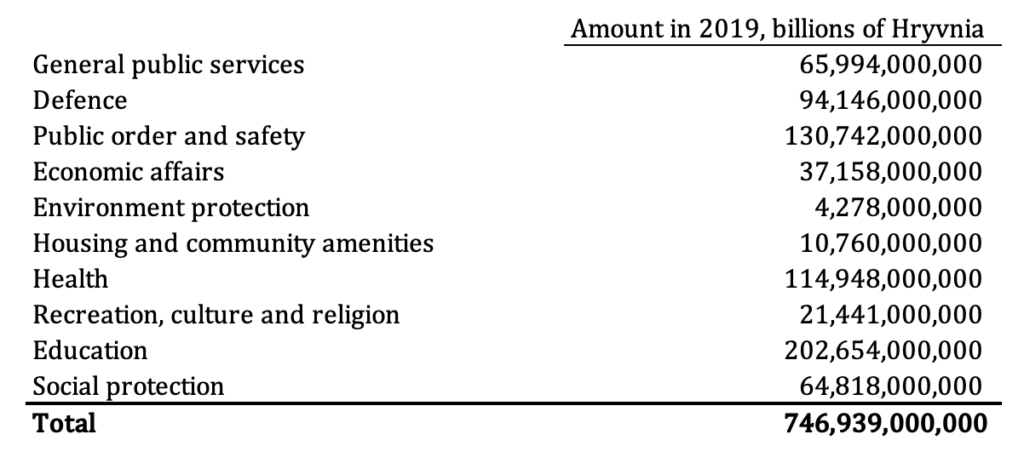

Table 1 reports a breakdown of public spending in Ukraine back in 2019:

Table 1

An average exchange rate for 2019 was 0.035 euros per Ukrainian hryvnia. Using this rate, we can convert the total amount spent into €26.1 billion. Defense spending amounted to €3.3 billion.

Again, this was six years ago, three years before Russia invaded Ukraine. Since then, things have changed dramatically.

Total Ukrainian government outlays from 2020 to2024 look as follows, according to the aforementioned United Nations database; amounts are in hryvnias (UAH):

- 2020: 819.6 billion

- 2021: 967.1 billion

- 2022: 2,087.1 billion

- 2023: 2,774.2 billion

- 2024: 2,094.3 billion

This 180% increase correlates well with the breakout of the war, suggesting that the bulk of the increase consists of defense spending. To isolate the defense outlays, we can assume that spending on all other items from Table 1 will remain relatively unchanged; their appropriations will grow along pre-war trends.

Assuming this stability in non-defense outlays, the defense budgets for 2023, 2024, and 2025 average UAH 1,155 billion per year.

If we exchange this for euros, and if we take into account that the Ukrainian currency in 2024 was worth only 0.022 euros per UAH, then Kiev’s defense outlays have risen to €26.6 billion annually.

Let us now go back to the €335 billion in frozen Russian assets. If we assume that these assets yield 3% per year—roughly what one could expect if they were invested in AAA-rated, euro-denominated sovereign debt—then the annual amount that can be collateralized by the Russian assets is €7.4 billion.

Not even a third of the estimated Ukrainian need in terms of military spending.

But wait—let us not forget that when Ursula von der Leyen spoke in Stockholm, she extended the support pledge to all of Ukraine’s government spending. Using, again, the 2024 exchange rate and the figure from the UN database, the EU and its member states would now be lending Kiev €41.2 billion—secured by a Russian-asset revenue stream that is only big enough for 16% of that loan.

Iam the first to admit that my estimates of Ukrainian public outlays are very rough estimates. They are based on data that in large part—but not entirely—goes back several years in time. However, they do raise the question that nobody wants to ask but everyone needs to answer: exactly what happens if the loans to fund Ukraine’s government are never paid back? Since the collateral for them only covers a fraction of the amount owed, the rest will fall on either of two sets of taxpayers:

- Russian taxpayers. This happens if the EU and NATO find some way to defeat Russia and force them to pay reparations to Ukraine.

- European taxpayers. This happens if the EU and NATO do not find some way to defeat Russia.

Russia has made clear that any military action by a foreign power that poses an existential threat to the country will be met with the use of nuclear weapons. Since Russia has jurisdiction over their definition of ‘existential threat,’ and since they possess what is probably the largest and most devastating arsenal of nuclear weapons in the world, the first of the two alternatives above is completely unrealistic.

In other words, unless Europe’s political leadership has signed a mutual civilizational suicide pact, the responsibility for funding the Ukrainian government for years to come falls on Europe’s already heavily burdened taxpayers. The only way to avoid this would be if the EU finds a way to seize the entirety of the €335 billion in frozen Russian assets. As Rafael Pinto Borges reports, the consequences of such a seizure would be ugly at best, catastrophic at worst, but even if these funds were seized and gradually utilized as ‘repayment’ of EU-sourced loans to Ukraine, the money would dry up quickly.

One final element of this numerical experiment remains to be considered. As it was worded, the pledge that von der Leyen made in Stockholm only pertains to the operational outlays of the Ukrainian government. If the EU would have any ambition to help Ukraine rebuild infrastructure and private-sector productive capital, they would have to expand their annual lending by €53-60 billion per year.

With that amount (derived from Ukrainian GDP figures, also courtesy of the UN National Accounts database) added to the direct fiscal help to Kiev, we are now somewhere in the vicinity of €100 billion per year.

With €335 billion in seized assets, the collateral for such loans to Ukraine would dry up in three short years. If, again, the EU even finds a way to actually take the frozen Russian assets.

Even if my numbers here come with a fair amount of uncertainty, there is one message in them that Europe’s political leaders—and certainly taxpayers—should not ignore. If there are no caps, either in time or in terms of money, on Europe’s financial commitment to Ukraine, then how much bigger will a European family’s tax bill be in a couple of years?

Original article: europeanconservative.com