In the global chessboard, Beijing will keep stressing the power of the “multilateral trading system.” As in the absolute opposite of Trump 2.0.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

Four days in Beijing. The fourth plenum of the 20th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China was really something to behold.

Methodology matters. What happened these four days is that delegates debated and then adopted “recommendations” leading to China’s 15th Five-Year Plan. A communique then laid out the basic vectors to be tackled. The full plan will only be known in detail next March, when it will be approved by the notorious Two Sessions in Beijing.

So let’s get straight to the point: this is how China works, meticulously planning everything in advance, with clear targets and meritocratic supervision. The – metaphorical – terminology does allow some leeway: everyone is aware of the “high winds, rough waves and raging storms” ahead – domestically and internationally. But “strategic resolve” won’t waver.

Key vectors for the Beijing leadership include “strengthening agriculture”, “benefiting farmers”, and “achieving rural prosperity” – side by side with progress with “people-centered new urbanization.”

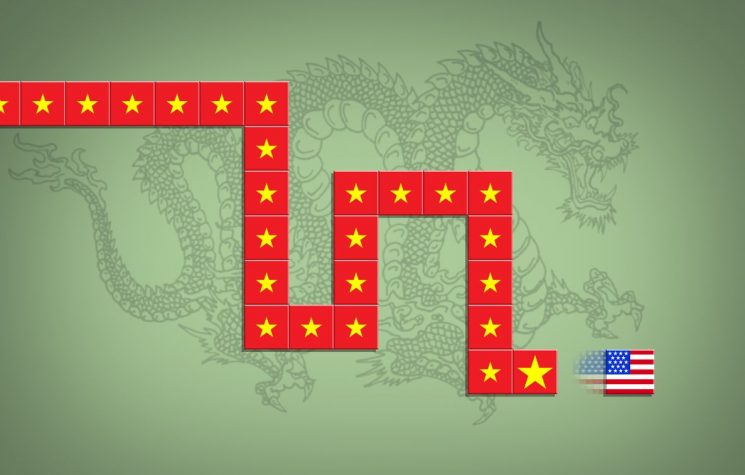

In the global chessboard, Beijing will keep stressing the power of the “multilateral trading system.” As in the absolute opposite of Trump 2.0.

Major targets for the 15th Five-Year Plan are quite clear. Among them: “advancements in high-quality development”; improving “scientific and technological self-reliance”; a quite Confucianist “notable cultural and ethical progress across society”; and “strengthening the national security shield.”

In a nutshell: the Chinese leadership’s top priority is to build “a modernized industrial system”. As in a productive – not speculative – mixed economic system driving rural, urban and tech development.

Towards an ultra-high-tech “unified national market”

There have been so many practical, graphic examples across China of what has been achieved so far. Last month, I was privileged to see first-hand the socialism with Chinese characteristics surge in terms of sustainable development of Xinjiang . Xinjiang is now an IT hub and a leader in clean energy – exporting to the rest of China.

Then there’s the tech accomplishments of Made in China 2025, launched 10 years ago, and already placing China as tech leader in at least 8 of 10 scientific fields. Plus key programs that many Chinese themselves don’t know about, with particualr emphasis on the 973 Program and Project 985.

The 973 Program, launched way back in 1997, is the National Basic Research Program aiming to get a tech/strategic edge in several scientific fields – especially the development of the rare earth minerals industry. The program definitely elevated China to the top in terms of global science competitiviness.

Project 985 was launched in 1998 to develop a select group of top-tier universities to world-class level. Hence the emergence of Tsinghua, Peking, Zhejiang, Fudan and Harbin Institute of Technology, among others, as world leaders in engineering, computer science, robotics, aerospace, including key breakthroughs in AI, quantum computing and green energy. Ivy League and Oxbridge? Forget it: the real deal is Chinese universities.

Another key project is the G60 Science and Innovation Corridor, connecting nine cities in China’s Yangtze River Delta. These cities contributed nearly 2.2% of global (italics mine) manufacturing value-added only last year. That’s China’s strategic economic planning driving tech progress – in effect.

At a press conference, Central Committee officials pointed to some basics obviously totally ignored by the fragmente West, but not by large sectors of the Global South. Especially the fact that Five-Year Plans are regarded as one of China’s key political advantages.

The formulation of the next plan, as usual in China, includes suggestions from all echelons of society. Market drivers from now on necessarily include computing infrastructure, intelligent driving and smart manufacturing. And predictably, up to 2035, there will be special emphasis on quantum tech, biomanufacturing, hydrogen, nuclear fusion, brain-computer interfaces, embodied intelligence and 6G, not to mention AI.

Conceptually, China will focus on its immense domestic market: what is defined as the “unified national market”.

A key emphasis was made on Beijing’s drive to combat “involution”: that is the intra-industry competition that has caused problems to several Chinese sectors.

On thorny US-China relations, Central Committee officials were adamant: the focus will be on “dialogue and cooperation” rather than “decoupling and fragmentation”. Well, both sides are meeting in Malaysia as we speak, on the sidelines of the ASEAN summit. Prospects for a wide-raing trade deal though are slim.

How to understand the evolution of the Chinese political system

The key takeaway: the 15th Five-Year Plan will concern the 2026-2030 period. Beijing wants to reinforce everything that was accomplished so far, with a crystal clear long-term focus: achieve what is defined as “socialist modernization” by 2035.

Based on what I personally saw in Xinjiang last month, compared to my previous visits (the last one had been over a decade ago), there is no shadow of a doubt they will do it.

It’s crucial to examine how two top Chinese academics explain the evolution of the Chinese political system. Relevant sections are worth quoting at length:

“While the traditional system was not immune to change, the goal of these changes was to maintain the status quo, preventing ‘revolutionary’ change. After the Han Dynasty, the policy of ‘abolishing all schools of thought and upholding Confucianism alone’ ideologically suppressed any factors that could catalyze major political change. Confucianism became the sole ruling philosophy, and its core purpose was to maintain rule. The modern German philosopher Hegel argued that ‘China has no history.’ Indeed, for thousands of years, from the Qin Shihuang Emperor to the late Qing Dynasty, China experienced only a succession of dynasties, not a change in fundamental institutions. Marx’s concept of the ‘Asiatic mode of production’ aligns with Hegel’s ideas. Chinese scholars such as Jin Guantao also have this in mind when they use the term ‘superstable structure.’ One can argue that this reflects the vitality of the traditional political system, or that China lacked structural change for thousands of years.”

“The current political system is quite different, primarily because the Enlightenment firmly established the concept of progress: that society can progress, and that progress is endless. From Sun Yat-sen’s revolution to Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist Party and then to the Communist Party, generations of Chinese people have pursued change, sharing the same goal: to transform China and achieve progress. During the modern Enlightenment, the Confucian individual ethic that sustained the old system was subjected to the most radical criticism and attack. However, while the old ethic is no longer viable, various political factions lack a consensus on what the future holds. What kind of change does China need? How should it be pursued? What is the purpose of change? Various political forces hold divergent views.”

What the Chinese Communist Party has done, the two scholars argue, is in fact quite revolutionary, going for radical change: “This is the socialist revolution it has pursued since its founding, using revolution to overthrow the old regime, thoroughly transform society, and establish an entirely new system. Naturally, this also leads to the various contradictions facing China today, most notably the conflict between traditional Confucian philosophy and Marxism-Leninism. The former is focused on maintaining the status quo or adapting itself for survival, while the latter pursues endless change.”

“Since the mid-1990s, the Chinese Communist Party has accelerated its transformation from a revolutionary party to a ruling party (…) One thing is clear: if a political party governs simply for the sake of governing, it will inevitably decline. This is evident in the history of communist rule in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, as well as in the historical and current experience of Western political parties that calculate their legitimacy based on votes.”

“After reform and opening up, the Chinese Communist Party redefined its modernity, aiming to achieve the original revolutionary goal of resolving the problem of ‘universal impoverishment.’ However, while redefining modernity, the Party also strived to preserve the ‘revolutionary nature’ of the ruling party (…) In terms of economic development, GDP-oriented economics played an invaluable role, transforming China’s ‘poverty socialism’ situation in just a few decades. By the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China in 2012, China had become the world’s second-largest economy and the largest trading nation, with per capita GDP soaring from less than $300 in the early 1980s to $6,000. More importantly, China lifted nearly 700 million people out of absolute poverty.”

The conclusion though is inescapable, and it is ineherent to the way Beijing is framing its political evolution now: “The Chinese Communist Party needs to redefine its modernity by reaffirming its mission, emphasizing its original aspirations, and reviving its revolutionary nature.”

After all, as the two scholars note, “in China, political parties are the subject of political action, and this action is not simply about survival and development, but about leading national development in all aspects (…) The ruling party must proactively define its own modernity through action, pursuing and achieving its own modernity. By constantly renewing and defining its modernity, the ruling party can maintain its sense of mission in leading social development while constantly renewing itself.”

There could hardly be a sharper summary of why socialism with Chinese characteristics is in a class by itself when it comes to translating political decisions into sustainable development targets. Complement it with Hong Kong billionaire’s Ronnie Chan’s succint analysis on the inevitability of the rise – again – of China.

The counterpoint is China ceasing to be the Pentagon’s key priority. Circus Ringmaster is essentially being forced to concede the global strategic competition to China. Forget about “winning” a tech/trade war on China – especially after the rare earth Sun Tzu move.

Meanwhile, the containment dogs bark while the Chinese Five-Year caravan strolls on.