Forget about barbarian propaganda. What really matters, historically, is that the Ancient Silk Roads as well as Xinjiang may well be the ultimate crossroads of civilizations. Along Central Asia, they are the (beating) heart of the Heartland.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

ON THE SOUTHERN SILK ROAD – Silk is the stuff of legend. Literally. At first manufactured only in China, silk historically was not only a luxury product but a monetary unit: a key element of trade and export revenues.

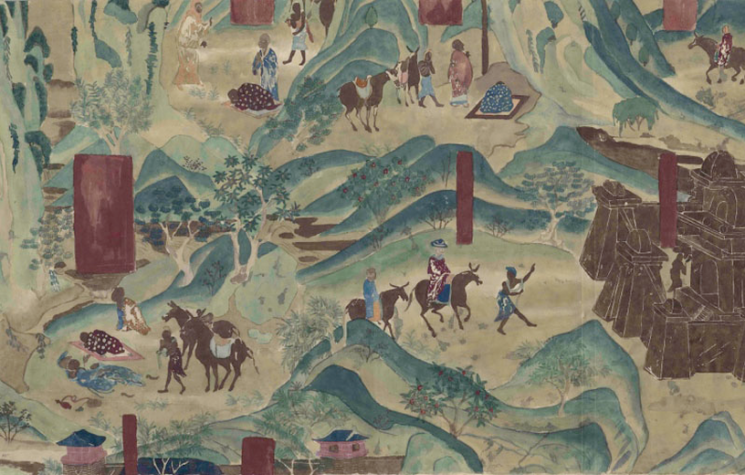

In 105 B.C., a first-ever Chinese diplomatic mission landed in Persia, then dominated by the Parthians, who also occupied Bactria, Assyria, Babylon and parts of India. Under the four-century long Arsacid dynasty – contemporary of the Han in China – the Parthians at the time were the essential middlemen of transcontinental trade. Chinese and Parthians sat down to discuss – what else – business.

The Roman Empire faced some serious trouble with the Parthians – between the massive defeat of Crassus in Carrhae in 53 B.C. and the victory of Septimus Severus in the year 202. In between, silk hit Rome. Big time.

The first time Roman soldiers saw silk was in the battle of Carrhae. Legend rules that the silk banners deployed by the Parthian army, their scintillating appeal making serious noise under the fierce winds, frightened the Roman cavalry: talk about the first instance of silk contributing to accelerate the decline of the Roman Empire.

Well, what matters is that silk perpetrated nothing less than an economic revolution. The Roman Republic and then Empire had to export gold like there’s no tomorrow to get their silken ways.

Parthian rule was followed by Sassanid Persia. They reigned until the mid 7th century – their empire stretching from Central Asia to Mesopotamia. For quite a while the Sassanids incarnated the role of great power between China and Europe – up to the conquests of Islam.

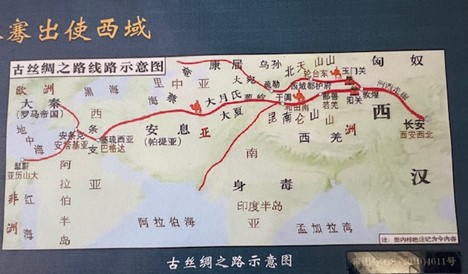

Silk Road, the ancient Chinese way: from Xian to Alexandria, not Rome. Photo: P.E.

So imagine, at the start of the Christian era, bolts of silk moving overland all along across the Silk Road spectrum. What’s fascinating is that Rome and China never (italics mine) entered in direct contact – for all the vast cast of characters (merchants, adventurers, fake “ambassadors”) that tried.

In parallel, a Maritime Road was also in play – already in effect during the times of Alexander The Great; it later became the Spice Route. That was how Chinese, Persians and Arabs reached India.

Since the Han dynasty, the Chinese reached not only India but also Vietnam, Malaysia and Sumatra. Sumatra soon developed as a key maritime entrepot, with Arab vessels arriving non-stop. In a more long-distance vein, it was the discovery of the rules of the monsoon – in the first century B.C. – that allowed the Romans to also reach the western shores of India.

So silk arrived in Rome by land and sea, via loads of different middlemen. And yet Rome never knew anything about the origin of silk, nor went further than the Greeks in their wobbly knowledge of the distant, mysterious land of Seres.

I went down to the (Pamir) crossroads

After the mid-1st century, the Kushan empire, actually Indo-Scythian, gets a protagonist role in southern Central Asia, in what was known then as Eastern Turkestan. The Kushan, rivals of the Parthians in the role of messengers of international trade, not only facilitated the spread of Buddhism but also Gandhara – Greco-Buddhist – art (some originals are still to be found today, at exorbitant prices, in art galleries in Hong Kong and Bangkok).

And yet, further on down the road, the rules of the game never substantially changed: two great Silk Road poles – Sassanid Persia and Byzantium – involved in a real, cutthroat industrial war with silk right in the middle. The secret of silk manufacturing had already been leaked to South Asia.

This trade war got even more complicated with the onslaught of Turk tribes across Central Asia, and the emergence of a trade kingdom in Sogdiana (with Samarkand at the center).

By the mid-7th century, the Tang dynasty recovered control over parts of the Silk Road ruled by Tarim basin kingdoms. That was an absolute must for business to go on – because caravan routes traversing these kingdoms encircled, and bypassed, by north and south, the fear-inducing Taklamakan desert, as they still do today.

Tang China wanted absolute control all the way at least up to the Pamir mountains where, in the legendary stone tower relentlessly described by adventurers but never really located with 100% certainty, Scythian, Parthian and Persian caravans met Chinese caravans to trade that precious silk plus several other commodities.

The stone tower: Tashkurgan Fort, the landmark between China and the rest of Eurasia. Photo: P.E.

The stone tower mentioned by top geographers such as Ptolemy is actually Tashkurgan Fort in the Pamir mountains: ultra- strategic, straddling the Silk Road, and nowadays a top tourist attraction very close to the Karakoram highway.

The stone tower is the symbolic landmark between the Chinese world and the rest of Eurasia: to the west is the Indo-Iranian world.

I traveled the Pamir Highway in Tajikistan back-to-back before Covid interrupted everything. This time our mini-caravan crossed Pamir lands along and around the Karakoram highway on the way to the China-Pakistan border: that is now prime China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) territory, a key plank of BRI.

On the road in the Karakoram – the Pamir way. Photo: P.E.

It’s the Pamirs that in Ancient Silk Road times allowed reaching the oasis of Kashgar. The Pamirs tie a gigantic mountainous knot between the western limits of the Himalayas, the Hindu Kush and the southern slopes of the Tian Shan.

The twists and turns of the Panlong Ancient Road, in Pamir lands. Photo: P.E.

This has always been the key crossroads between the triangular trade uniting northern India, eastern Central Asia – with China nearby – and western Central Asia, with the steppes not so far away.

China meets Islam: a great, historical “what if?”

Silk, bearing serious value as a unit of capitalization and trade, had a much larger role than its usage. In Byzantium, silk was the object of an imperial monopoly. Everything was strictly regulated: professions, state ateliers where women worked, and customs. The state protected its monopoly via a fierce bureaucracy.

Meanwhile, the Maritime Road was booming. A Buddhist and maritime power, Srivijaya, controlled the ever-crucial Malacca strait out of the island of Sumatra. It’s under this configuration that Islam enters the Big Picture.

As much as History ruled that Rome and China would never meet directly along the Silk Road, it also ruled a stark separation between Islam and China. Or try to imagine if China, in the mid 8th century, had become a land of Islam.

The battle of Talas, in 751 – in what is today’s Kyrgyzstan – pitted China against the Arabs. And its result ended for good any Chinese whim of conquering Central Asia. Today, with the New Silk Roads/BRI, is another story – about Chinese trade/investment power projection all across the Heartland, and beyond.

Culture interpenetration: Bukhara meets Kashgar. Photo: P.E.

Back in the early 8th century, the key player was Umayyad dynasty General Qutayba ibn Muslim. He first conquered Bukhara and Samarkand; crossed the Ferghana valley; the Tian Shan mountains; and nearly reached Kashgar. The Chinese governor at the time, sensing that Qutayba might be about to take over Chinese lands, sent him a bag full of earth’s soil, a few coins and four princes as hostages. He calculated that’s how the Arab conqueror might not lose face, and leave the Middle Kingdom alone.

As incredible as it might seem, this arrangement lasted for half a century. Until the battle of Talas. Now compare it with Poitiers in 732 – one century after the death of Prophet Muhammad. We can certainly interpret Talas and Poitiers, together, as the two key landmarks of how Islam was on the verge of extending itself all cross Eurasia (including its European peninsula), creating a political-military empire from Rome to Chang’an (today’s Xian).

Well, it did not happen. Still, that’s one of the most extraordinary “what ifs” in History.

The importance of the battle of Talas – virtually ignored in the West, except in rarefied scholarly circles – is really larger than life. Among other issues, it imposed a new circulation of techniques. The Arabs took away with them artisans, sericulture experts but also paper makers. Ateliers at first were set up in Samarkand. Later on, in Baghdad and all across the Caliphate.

So alongside the Silk Road, we saw the birth of a very busy Paper Road.

Deserts, mountains, oases – and no “slave labor”

Rolling down the highways across Xinjiang shooting a documentary after retracing the initial Ancient Silk Road from Xian to the Gansu corridor is an incomparable, historical time travel – as we may retrace in detail centuries of Central Asian turmoil all the way to the decline of some local pre-Islamic cultures by the 9th century. It’s a thrill to reconnect with the main actors: Uyghurs, Han Chinese, Sogdians, Indians, nomads, Arabs, Tibetans, Tajiks, Kyrgyz – and Mongolians.

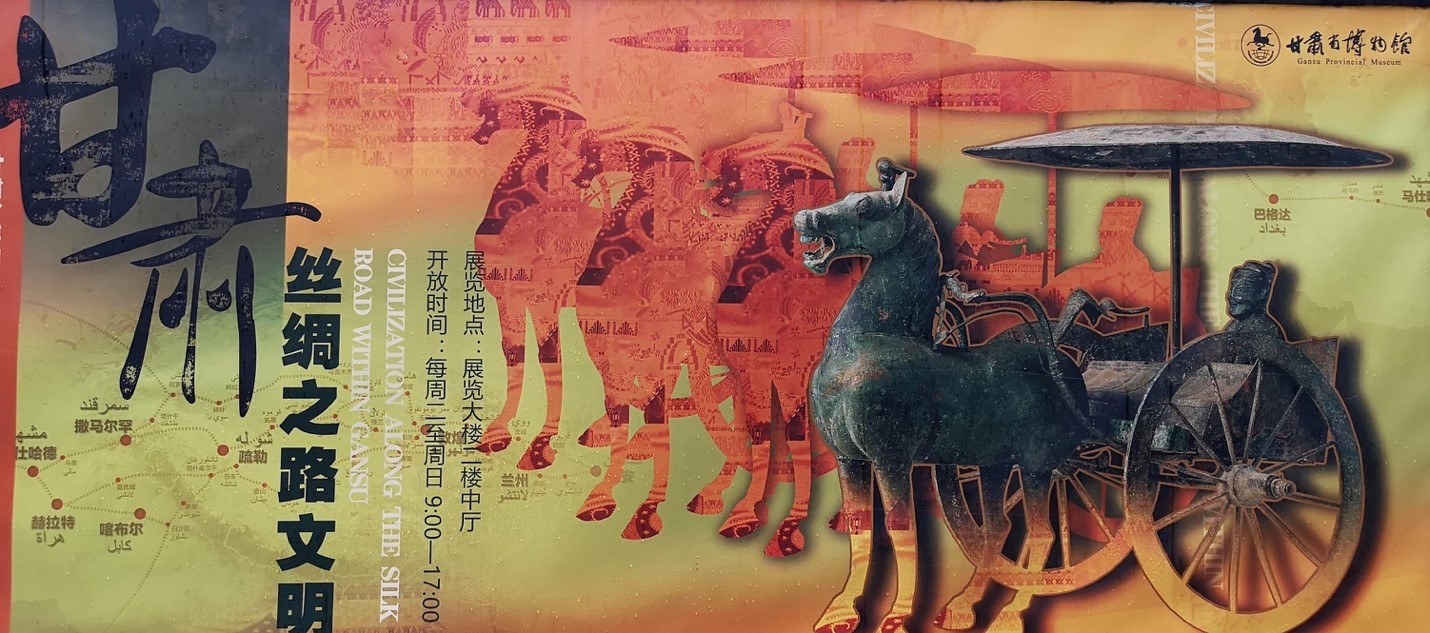

An extraordinary Silk Road exhibition currently at the Gansu museum in Lanzhou. Photo: P.E.

The nomad groups thar proclaimed themselves heirs to the fierce Xiongnu came from the northwest of Mongolia and the Altai mountains. They incorporated several ancient nomads of western Central Asia during the 4th century, sharply remodeling the political and ethnic landscape.

The Xiongnu, on and off, pillaged parts of northern China – and were occasionally enticed into serious trade, offered tribute, or simply bribed to stay away. Actually the Xiongnu had a branch established in China and separated for at least two centuries from the previous ones: they ended up taking Samarkand in the year 350. Later on, it’s the Turks that once again came from Mongolia (don’t tell Erdogan about it; he wouldn’t know), unifying the steppe in the 6th century, way before the arrival of Islam.

Arguably the key Silk Road imperative is the desert and oasis contrast/dichotomy.

The stark beauty of the fierce Taklamakan. Photo: P.E.

Deserts such as the Taklamakan and the Gobi, and several others, as well as arid steppes and mountains are among the most forbidding on the planet: these are the essential features of what amounts to roughly 6 million km2.

What is very rare in Central Asia is cultivated land (yet we can see a succession of cotton fields) or good pasture (we can see it in the Gansu corridor, and even in Pamir lands near the mighty Muztagh Ata). Still, deserts and mountains are at the heart of everything.

Good pasture in Pamir lands. Photo: P.E.

Some oases are of course more equal than others. Khotan is the most important oasis of the Southern Silk Road – not far from the immense, deserted Tibetan plateau. That’s fabulous for agriculture but most of all, courtesy of an alluvial cone, for precious stones, especially jade, supplied for over 2,000 years to every Chinese dynasty. Khotan spoke an Iranian language – close to those of ancient nomads Saka and Scythian, masters of the steppes.

The Chinese character for “silk” inscribed in jade in front of a factory in Khotan. Photo: P.E.

The kingdom of Khotan was a fierce rival of the oases further west, Yarkand and Kashgar. It was only intermittently under Chinese control. And may have been conquered by the Kushans in the 2nd century. Indian influence is omnipresent – as we still see in dress patterns and food in the Night Market. In the 3rd century Buddhism was already a major influence – featuring the most ancient testimonials in the Tarim basin.

The Silk Road, actually Roads, is of course The Buddhist Road. In Dunhuang, in the Gansu corridor, Buddhism was also popular since the 3rd century: a famous local monk, Dharmaraksa, was the pupil of an Indian master. The Dunhuang Buddhist crowds were a mix of Chinese, Indian and Central Asian – once more testifying to the non-stop interpenetration of cultures.

The camel caravan in the era of booming domestic tourism, outside Dunhuang. Photo: P.E.

The Shakespearean “all the world is a stage” metaphor totally applies to the history of the Silk Road: all those actors from all corners of the Heartland historically were playing several roles, sometimes all in one go – an apotheosis of the favourite Xi Jinping-coined “people to people’s exchanges”. That’s the spirit of the Ancient and the New Silk Roads.

Playing the Uyghur blues. Photo: P.E.

We were fortunate enough to be on the road smack in the middle of the 70th anniversary of the establishment of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region.

Among so many accomplishments by socialism with Chinese characteristics in Xinjiang in terms of sustainable development, the taming of the Taklamakan – or “sea of death” – is in a world class of its own.

We crossed the Taklamakan from the Northern Silk Road in Aksu to the Southern, near Keriya: and we experienced everthing from the impeccable highway bordered by the reeds composing the “China magic cube” – to keep the sands away – to some of the 3,046 km-long sand-blocking green belt, featuring plants such as the desert poplar and the red willow.

The Taklamakan has always been Sandstorm Central – a major threat to the succession of oases. The terrain all around the oases is hardcore: deserts, barren mountains, Gobi wasteland, poor soil, sparse vegetation, low rainfall, high evaporation, dry air.

Well, what we see today started even before the Go West campaign launched in 1999: since 1997, an array of central and state agencies, central state-owned enterprises, and 14 Chinese provinces and municipalities have sent a massive amount of funds and personnel to properly develop Xinjiang.

Now compare all that with original research shared at an academic conference on Xinjiang recently organized by the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology and Hong Kong University – my neighbors when I lived in the Fragrant Harbor. The research showed how British MI6 since the 1990s was instrumentalizing a minority of Uyghurs side by side with a massive global P.R. campaign with the explicit target of breaking China into three parts.

That evolved into the CIA-concocted “genocide” accusations of the past few years and of course “forced labor” masses barely surviving in concentration/re-education camps. In our extensive travels, guided by Uyghurs, we were dead set on finding slave labor in cotton fields along the Northern Silk Road or in the middle of the Taklamakan. Well, sorry: they don’t exist.

The propaganda though was essential to regiment loads of Uyghurs into ISIS, including their sizable contingent in Idlibistan now roaming free between Syria and the Turkish border. They wouldn’t dare coming back to Xinjiang and face Chinese intel.

Forget about barbarian propaganda. What really matters, historically, is that the Ancient Silk Roads as well as Xinjiang may well be the ultimate crossroads of civilizations. Along Central Asia, they are the (beating) heart of the Heartland. And now, once again, they are back as protagonists in the heart of History.