The future of the former “Western Regions”: an energy-rich, multi-cultural, multi-religious, geostrategic New Silk Road hub of “moderately prosperous” China.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

YUTIAN, ON THE SOUTHERN SILK ROAD – We are on the road in southern Xinjiang, after a harrowing back-and-forth in the Taklamakan, across the sand dunes, to visit the “lost tribe” cum village of Daliyabuyi, right in the middle of the desert, then back to our drop-dead modern hotel in the oasis of Yutian. It’s midnight, we just finished the proverbial Uyghur gastronomic feast, and there’s only one thing to do: to get a shave.

The perks of being on the road in Xinjiang to shoot a documentary supported by a crack Uyghur production team – drivers included – is that they know everything. “No problem”, says one of the drivers, “there’s a barber shop on the other side of the street.” Actually, a boulevard gleaming at midnight. Shops still open. Life goes on as usual in Uyghurstan.

With my friend Carl Zha, we cross the street and hit the barber shop just to plunge into a fabulous slice of (Uyghur) life, courtesy of two young barbers and their sidekick, a snazzy kid playing a videogame compulsively on his smartphone who seems to know everything about the hood (he may be even running it, wise guy-style).

They tell us everything about their daily routine, flow of business, cost of living, sports, life in the oasis, chasing girls, their expectations for the future. No, they are not refugees of concentration camps. Nor slaves under forced labor. An hour and a half with them, and you have a PhD in Uyghur social studies, live. With the added bonus of getting a haircut (Carl) and a shave (myself) for under 10 bucks at one in the morning.

We were ready for the next day on the road – when we formally completed the Silk Road triad: Silk, Jade and Carpets. Silk and carpets in the fabled oasis of Khotan – watching how they have been produced for centuries.

Carpet weaving in Khotan. Photo: Pepe Escobar

And jade in Yutian itself, which is not as famous, historically, as Khotan, but now boasts a state-of-the-art jade company involved in everything from mining to the refined final product, including the finest grade: black and white jade.

Polishing the finest jade in Yutian. Photo: P.E.

In fact, it’s a Silk Road quartet, because we should add knives, in the small oasis of Yengisar, world capital of jeweled knife production. Every Uyghur man carries a knife: as a sign of manhood and to cut those juicy Xinjiang melons at any opportunity.

Yengisar: the knife capital of the world. Photo: P.E.

Throughout the Northern Silk Road, we were of course on the lookout non-stop for labor slaves and concentration camps to be duly reported to Western intel agencies. Then, on the way from Kucha to Aksu, we spotted a lady among the rolling cotton fields.

The lady in the cotton fields. Photo: P.E.

We started to chat, and soon found out that she was not picking cotton: she was actually clearing the path in the cotton plantation for a machine to make a turn and then start picking cotton mechanized agriculture-style. She told us everything about her daily life; she was a local Uyghur, had been working on this same – private – cotton fields for nearly two decades, living with her family, decent salary. Never seen a forced labor/concentration camp in her life.

Enjoying real Uyghur life in oasis towns

Across both the Northern and Southern Sik Roads, in historically key oasis towns from Turfan and Kucha to Khotan and Kashgar, we followed daily Uyghur life unfiltered, introduced by Uyghurs and among Uyghurs. Politics never entered the conversation.

We were invited into their sprawling homes – large courtyards, grapes growing on the roof; we went to two weddings, one relatively low-key in a four-star hotel, another a Bollywood production in the top restaurant in Kashgar.

Over the top Uyghur wedding in Kashgar. The bride and groom are sitting right behind “Love”. Photo: P.E.

We talked to barbers, bakers, bazaaris, business men and women. We sampled their spectacular cuisine with relish; yes, the meaning of life is contained in the perfect bowl of laghman, with the perfect naan bread on the side.

The Holy grail of Uyghur gastronomy: laghman, plov and Kashgar barbecue. Photo: P.E.

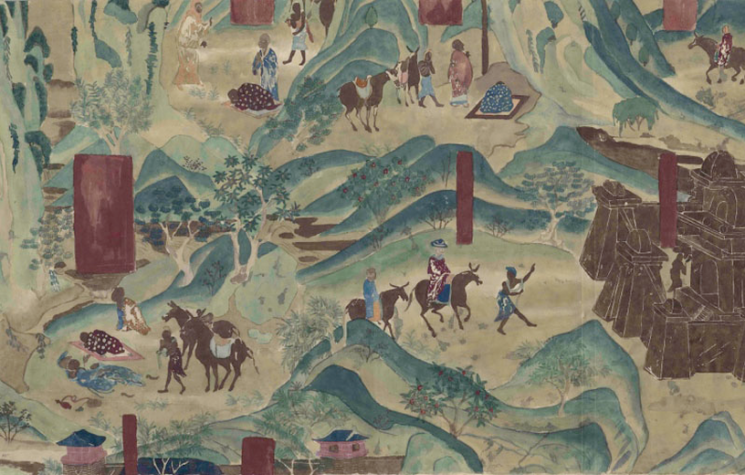

More than that – an obsession I carried since my first Silk Road travels in 1997, right after the Hong Kong handover: I wanted to retrace and dig deeper into the mesmerizing Ancient Silk Road history of those oasis towns, following once again on the footsteps of my man: the itinerant monk Xuanzang in the early Tang dynasty.

So this updated Journey to the West was, in so many ways, a Journey to the Buddhist “Western Regions” before they became part of China.

Both Turfan and Kucha were key stops in Xuanzang’s Journey to the West in the early 7th century. Then, equipped with camels, horses and guards, he crossed the Tian Shan mountains, met the kaghan of the Western Turks (who wore a fine green silk robe and a 3-meter long silk band around his head) on the edge of deep blue Lake Issyk-kul (in today’s Kyrgyzstan) and kept walking all the way to Samarkand (in today’s Uzbekistan).

All that is like a miniature jade representing the Silk Road allure – intertwining the connection between Chinese culture, Buddhism, Sogdians (the Persian people who were the key connectors in Silk Road trade and the most influent immigrant community in China during the Tang dynasty) and Persia itself.

In Samarkand, Xuanzang was exposed for the first time to extremely rich Persian culture – so different from equally sophisticated China’s. And it was Samarkand – not Rome – which was the most important trade partner of the independent Gaochang kingdom in the 5th century, and then the Tang dynasty.

The remains of the Gaochang kingdom – outside of Turfan.

And that bring us to some fascinating geo-strategic and geoeconomic aspects of the Ancient Silk Road(s).

Very few people apart from top scholars – and economic planners around Xi Jinping – know that the key player in the Silk Road economy especially during the Tang dynasty, from the 7th to the 10th centuries was… the Tang dynasty itself. It was a matter, above all, of financing the then “Western Regions” in a serious military confrontation against the Western Turks.

So we had Tang armies positioned all along the oases of the Northern Silk Rod, with an interesting twist: most of them were not Chinese, but local, from across the Gansu corridor and the “Western Regions”.

There was a non-stop back-and-forth of conquests and losses. For instance, the Tang dynasty lost the all-important oasis of Kucha to the Tibetans from 670 to 692. The result: increased military expenditure. In the years 740, the Tang dynasty sent no less than 900k bolts of silk each year to four military HQs in the Western Regions: Hami, Turfan, Beiting and Kucha (all top Silk Road oases). Talk about supporting the local economy.

A few dates tell us how the geostrategic scenario changed non-stop. Let’s start with the early 800s, when Uyghurs actually began to rule Turfan. By then the Uyghur kaghan met a teacher from Sogdiana – the lands around Samarkand – who introduced him to Manicheism, the fascinating religion founded in Persia by Mani in the 3rd century, according to which the forces of light and darkness are forever fighting to control the universe.

The Uyghur kaghan then made a fateful decision: he adopted Manicheism – recording it in a trilingual stone tablet (in Sogdian, Uyghur and Chinese).

The long march from Buddhism to Autonomous Region

The Tibetan Empire was also very strong in the late 700s. In 780s they moved into Gansu and in 792 they conquered Turfan. In 803 though the Uyghurs got Turfan back. But then the Uyghurs still living in Mongolia were defeated by the Kyrgyz in 840; some of them actually ended up in Turfan, and established a new state: the Uyghur Kaghanate, whose capital was Gaochang City, which I had the pleasure to finally visit.

The ruins of Gaochang city. Photo: P.E.

So only then Turfan became Uyghur, using the Uyghur language, and not Chinese, for trade. That went on for centuries. The economy was largely focused on barter, with cotton replacing silk as a currency. Religiously, under the Tang dynasty, the people of Turfan was a mix of Buddhists, Daoists, Zoroastrians and even Christians and Manichean. A small church, evidence of Eastern Christianity, based in Mesopotamia, with Syriac as the liturgical language, was found in the early 20th century by German archeologists outside the eastern walls of Gaochang.

So Manicheism for a while actually became the official state religion of the Uyghur Kaghanate. Their art was absolutely exceptional. Yet only one Manichean cave painting still survives – at the stunning Bezeklik caves. I paid 500 yuan for the privilege of seeing it, guided by a very knowledgeable young – Uyghur – researcher.

The reason for the vanishing Manichean art murals is that around the year 1000 the Uyghur Khaganate decided to go full Buddhism, abandoning Manicheism. Even the now notorious cave 38 in Bezeklik (the one I visited, no photos allowed) shows the evidence: the caves had two layers, with a Manichean layer beneath a Buddhist layer.

Politically, the back-and-forth continued unabated: that’s prime Silk Road history. In 1209 the Mongols defeated the Uyghur Khaganate in Turfan – but left the Uyghurs alone. In 1275 the Uyghurs allied themselves with legendary Kublai Khan. But then peasant rebels ended up toppling Pax Mongolica and establishing the Ming dynasty in the 14th century: but Turfan, significantly, still remained outside the borders of China proper.

A crucial date is 1383: Xidir Khoja, a Muslim, conquered Turfan and forced everyone to convert to Islam: that lasts until today. At least on the surface: when you ask people in oasis towns in Xinjiang if they are Muslim, many politely decline to answer. The Buddhist past remains – in the collective unconscious – and visibly, in the spectacular ruins of Gaochang.

Xinjiang, crucially, remained independent of China until 1756, when the Qing dynasty armies took over. During our on the road last month, we were smack in the middle of the 70th year of the foundation of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. The whole of Xinjiang was enveloped in red flags and banners with the number “70”.

Urumqi: celebrating 70 years of Xinjiang. Photo: P.E.

That’s the future of the former “Western Regions”: as an energy-rich, multi-cultural, multi-religious, geostrategic New Silk Road hub of “moderately prosperous” China.