Washington should be directing its efforts towards reinforcing Venezuelan stability, especially through the withdrawal of sanctions.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

It would be a mistake to say that with Trump’s return to the White House, Venezuela is once again under pressure. It never stopped being under pressure since the final years of the Obama administration. But it is legitimate to say that Trump 2.0 has initiated a new phase in the over-10-year hybrid campaign against the Bolivarian state.

We have already seen sanctions, attempts at color revolution, attempts to install an “alternative” president, the theft of Venezuelan gold reserves, the refusal to recognize the legitimacy of elections, provocations at the borders, and even the blocking of its entry into BRICS (sadly spearheaded by Brazil).

Now, however, we see military threats looming on the horizon against Caracas.

Harbingers of this had already occurred.

In 2020, for example, there was an attempt to infiltrate Venezuelan territory with mercenaries hired by the American company Silvercorp with the goal of overthrowing the government of Nicolás Maduro.

In 2024, the CEO of the former private military company Blackwater started the “Ya casi Venezuela” project to raise funds with the alleged aim of overthrowing Nicolás Maduro. Recently, he also stated that the $50 million bounty should apply not only to Maduro’s capture but also to his assassination.

And, as we know, between late August and early September, we saw a series of events that raised tensions in the Caribbean Sea, such as the deployment of warships to the Caribbean and the bombing of four Venezuelan boats that were allegedly transporting drugs.

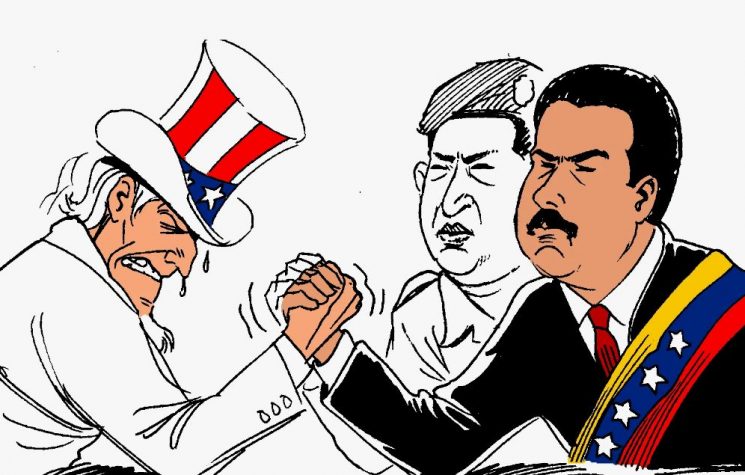

Now, despite the official line that U.S. maneuvers in the Caribbean Sea are aimed at combating drug trafficking, it is noteworthy that Venezuela accounts for only 3% of all drugs reaching the U.S.. Washington does not seem to be deploying the same level of effort to stifle more important sources, such as the Colombian route, for example.

Thus, even without any official declaration, one cannot rule out the possibility that the U.S. is considering moving forward with a new attempt at regime change in Venezuela – but this time in a more direct way, whether through naval and aerial bombardments, drone attacks, or a black ops operation using mercenaries and/or special forces. Or, of course, a combination of all these options.

Naturally, one thing is to set this objective, another is to achieve it, and yet another thing is to deal with the consequences afterward.

From what is known about the fall of Assad, for example, it was apparently achieved, at least in part, by bribing military officers and co-opting Syrian intelligence. The classic tactic of “divide et impera,” divide and conquer, was used to liquidate Syrian power and facilitate the state’s conquest by Al-Julani’s irregular forces.

Any similar attempt regarding Venezuela will fail. Indeed, Venezuela, as a poor country, would in theory suffer from this fragility facing the possibility of its officials being bribed by foreign economic powers, but the Venezuelan Armed Forces were built in a different way from other states, as is the very foundation of Venezuelan state power. The degree of civilian-military integration in Venezuela is such that the supervision of numerous economic activities in the country is carried out by high-ranking military officers.

The Venezuelan state is, at least in part, a military state. The military does not represent an isolated institution separate from political power, available, therefore, for the possibility of co-option and instrumentalization against other institutions. Instead, in terms explained decades ago by the Argentine philosopher Norberto Ceresole, the military constitutes the guard of the Bolivarian Revolution.

Furthermore, Venezuela’s intelligence agencies, SEBIN and DGCIM, are very closely linked to both military and political power. It is these agencies that have been instrumental in all infiltration attempts in Venezuela, and it is unlikely that dissent can be cultivated within these structures.

Finally, although the Bolivarian militias are not very useful against long-range missile attacks, from the perspective of law and order and guaranteeing national stability in the face of the possibility of trying to take advantage of a potential chaotic situation to organize a color revolution, the armed Bolivarian militias can play a subsidiary and supportive role for the authorities, stifling potential foci of dissent and rebellion.

Now, even the goal of overthrowing Nicolás Maduro’s government presents difficulties even if eventually achieved. Other hierarchs could take his place, as they would have the support of the Venezuelan Armed Forces; this could lead to a scenario of prolonged conflict on Venezuelan territory.

As in all cases of a country’s destabilization, emigration tends to increase rather than decrease, due to the greater difficulty of ensuring the common good in the first months after a hypothetical overthrow of Maduro.

Although the U.S. has a tendency to destabilize nations to keep them in a state of permanent chaos, in theory, the same could not be done in Venezuela lest the instability reach the U.S. itself through increased migration and the collapse of law and order.

U.S. security itself also depends on maintaining a stable Venezuela, so the U.S. would truly be forced into “nation-building” in Caracas, facing a heavily armed country, including at the civilian level, and one that is predominantly hostile.

Instead of such adventurous delusions, Washington should be directing its efforts towards reinforcing Venezuelan stability, especially through the withdrawal of sanctions.