Full and effective independence, with sovereignty and autonomy, is possible, but it is still a work in progress.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

Leading the way to a better future

A word of advice: keep your eyes on what is happening in the Sahel. And, above all, do not ignore the underlying reasons and the ways in which Africa is now rising again thanks to the Alliance of Sahel States.

Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger are three contiguous, landlocked states that occupy a huge swath of territory straddling the southern Sahara and the Sudano-Sahelian region. Together, they account for almost half of West Africa’s total area—about 45%—and about 17% of its population, with a combined total of over 73 million inhabitants (26.2 million in Niger, 23.8 million in Mali, and 23 million in Burkina Faso). These figures alone demonstrate the demographic and geographic weight of the Sahelian triad.

The societies of these countries share strong common traits, the result of centuries of cultural and commercial exchanges and geographical proximity that has fostered the sharing of social norms and practices, cultures still largely based on community values, oral tradition as the preferred means of transmitting knowledge, predominantly agricultural economies, and social structures strongly influenced by religion, which shapes people’s lives in a vertical openness to existence.

Like the rest of West Africa, Niger, Mali, and Burkina Faso experienced all the contradictions of French colonial rule in the 20th century, contradictions that exploded in a dramatic fashion during World War II. The official European narrative rarely mentions that a significant proportion of the soldiers and laborers employed to liberate Europe from Nazism came from the French colonies in West Africa, including present-day Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger. Thousands of Africans fought and died on European soil, and their war experience fueled a new political consciousness that paved the way for demands for equality and self-determination.

The first anti-colonial organizations

It was after World War II, in a context of attempts to establish socialism in Africa, that anti-colonial movements took hold and achieved significant successes.

Let’s proceed in historical stages. In Niger, the Nigerien Progressive Party was founded in 1946, affiliated with the Rassemblement Démocratique Africain, a large pan-African and anti-colonial coalition led by figures such as Modibo Keïta in Mali and Ahmed Sékou Touré in Guinea. The RDA began by demanding equal rights with French citizens, but within a few years it moved to a position of total break with the colonial system.

In Burkina Faso, the Voltaic Union joined the RDA to build a common front for liberation on a regional scale. Socialism in Burkina Faso took on a particular connotation during the presidency of Thomas Sankara, who transformed the then Upper Volta into Burkina Faso, ‘the land of honest men’. His vision, inspired by Marxism-Leninism but deeply adapted to the African context, aimed at a model of autonomous development based on social justice, popular participation, and economic independence from colonial powers and international financial institutions.

Sankara launched a vast program of reforms that included land redistribution, the promotion of subsistence agriculture, and mass literacy. Thousands of schools, wells, and health centers were built in rural areas with the aim of reducing inequalities between cities and the countryside. His policy encouraged the role of women, abolishing oppressive traditional practices and promoting their active integration into the economic and political life of the country.

Burkinabe socialism differed from the Soviet model in its strong community roots and focus on self-sufficiency. It openly criticized foreign debt, considering it a mechanism of neocolonial subjugation, and rejected the personal enrichment of leaders. Sankare’s leadership was austere and charismatic, as he sought to build a sense of national identity and solidarity among citizens at a time of great difficulty for the African peoples of the Sahel.

Despite significant achievements in terms of social and infrastructural development, Burkina Faso’s socialist project met with internal and external resistance. A lack of resources, international isolation, and conflicts with local elites led to growing tensions, culminating in the 1987 coup d’état in which Sankara was assassinated.

Immediately afterwards, Blaise Compaoré took power, ushering in a thirty-year period characterized by a gradual abandonment of socialist policies. The new regime sought to normalize relations with Western powers and international financial institutions, liberalizing the economy and reducing the scope of Sankara’s popular reforms. This transition generated growing disillusionment among citizens, as promises of inclusive development and social justice gave way to corruption, inequality, and instability.

In 2014, a popular movement forced Compaoré to resign, ushering in a period of political uncertainty with weak civilian governments unable to respond to rising insecurity, exacerbated by the spread of jihadist groups in the Sahel. Subsequent presidents, Roch Marc Christian Kaboré and Paul-Henri Damiba, failed to stabilize the country or resume the path of social development, fueling discontent.

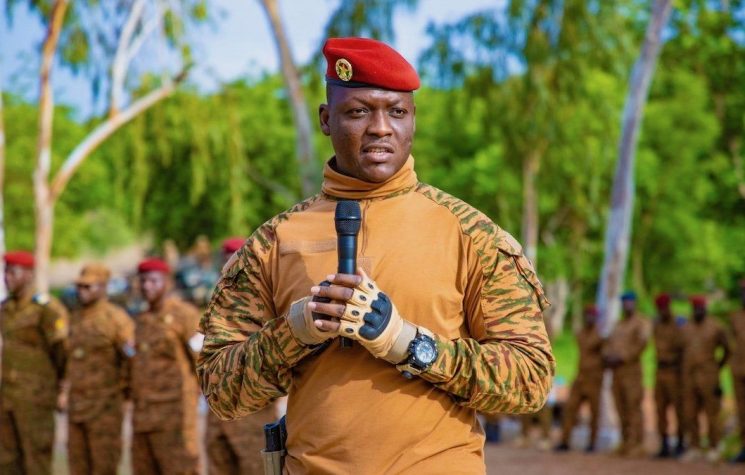

In this context of crisis, the military leader Ibrahim Traoré seized power in a coup d’état in September 2022, reviving Sankara’s socialist and independence dream and becoming a beacon for all oppressed peoples around the world.

The international situation had accelerated this process, especially due to the political presence of France and the UK. France’s heavy defeat in Indochina in 1954 and the intensification of the war in Algeria, which lasted until 1962, reduced Paris’s ability to maintain control over its colonies. Charles de Gaulle attempted to preserve at least part of the empire by offering a compromise: in 1958, he called a referendum on the new Constitution of the Fifth Republic. The African territories were offered two options: vote ‘yes’ to remain in the French-African Community, keeping the centers of power under French influence, or vote ‘no’ for immediate independence, but risking political rupture and economic isolation.

Djibo Bakary—founder of the Sawaba party (which means “freedom” in the Hausa language) and head of government after the 1957 elections—led the “no” campaign. Only Sékou Touré’s Guinea really managed to reject De Gaulle’s offer, gaining immediate independence in 1958 as the first French colony in West Africa.

Leaders in favor of breaking away were often subjected to internal repression, fueled by cooperation between colonial officials, traditional leaders, and the new African “évoluée” elite educated in French schools and destined to perpetuate the existing order. De Gaulle sent a new governor, Don Jean Colombani, who mobilized the entire administrative and security apparatus to sabotage the referendum and weaken the Sawaba, which was also opposed to French exploitation of Nigerien uranium. The “yes” vote officially prevailed thanks to massive electoral manipulation.

Nevertheless, Guinea’s victory in 1958, following the independence of British Ghana in 1957, forced Paris to gradually give ground. In 1960, as many as 17 African states—14 of which were former French colonies—proclaimed independence. However, this was largely a case of “independence with a flag”: the national symbol changed, but not the economic structure. French influence remained intact thanks to a dense network of ‘cooperation’ agreements which, through technical assistance protocols, defense agreements and, above all, the CFA franc system, ensured Paris substantial control. These agreements obliged African states to repay the infrastructure built during the colonial period (often with forced labor), granted France preemptive rights on strategic exports—particularly uranium—guaranteed French companies tax exemptions thanks to the principle of non-double taxation, imposed the use of the CFA franc controlled by the French Treasury, thus limiting monetary and fiscal sovereignty, and maintained French military bases with free use of infrastructure, including communications and transmissions.

The case of Niger is emblematic. A 1961 defense agreement with Côte d’Ivoire and Dahomey (now Benin) granted France unlimited use of military infrastructure and assets and explicitly defined the role of the French armed forces as guarantor of economic interests, listing strategic raw materials (hydrocarbons, uranium, thorium, lithium, beryllium) and obliging the signatory countries to inform Paris of any export projects and to facilitate the storage of these resources for French defense needs. In this way, the military apparatus became a real instrument for protecting the commercial and geopolitical interests of Paris, which did not want to leave Africa, too important to maintain its colonial financial power and manage its internal wealth on the European continent.

Autonomy and retaliation

After independence in 1960, Modibo Keïta’s Mali sought to embark on an autonomous path inspired by socialism: the creation of state-owned enterprises, the nationalization of key sectors, and, above all, the introduction in 1962 of a national currency outside the CFA franc area. The French reaction was immediate: diplomatic isolation, trade restrictions, and suspension of technical and financial assistance. The resulting economic crisis paved the way for the 1968 coup d’état by Lieutenant Moussa Traoré, supported by France, which brought Mali back into the CFA franc zone in 1984.

In the 1980s and 1990s, with the end of the Cold War, Paris reformulated its African policy by introducing ‘political conditionality’: at the 1990 La Baule summit, François Mitterrand declared that aid would be linked to democratic reforms such as multipartyism. At the same time, the IMF and the World Bank imposed Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs): austerity, public sector cuts, trade liberalization. In Mali, these packages accompanied the return to the CFA franc in 1984.

The devaluation of the CFA franc in 1994 was a second shock: officially, it was intended to boost exports and stabilize finances, but in reality it led to price increases, wage erosion, and widespread protests. This new phase combined economic liberalization and externally imposed governance reforms: a facade of “democratization” that consolidated neocolonial control through debt, privatization, and donor-led state restructuring.

These instruments of domination were gradually joined by a Western military presence, particularly from the U.S., when in 2002 the U.S. launched the Pan-Sahel Initiative, which marked the beginning of a lasting military presence in Mali, Niger, Chad, and Mauritania, later extended to Burkina Faso with the Trans-Sahara Counterterrorism Partnership of 2005.

Since 2011, French and U.S. operations have intensified: U.S. drones, training missions led by AFRICOM, military bases in Gao, N’Djamena, Niamey, Ouagadougou, France’s Operation Barkhane, and the G5 Sahel joint force (Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, Niger). Much has changed. Religious terrorism has also been present, keeping the region in a state of precariousness and insecurity, becoming a scourge that is difficult to combat in many areas.

It was in that same year, 2011, that the planned destruction of Gaddafi’s Libya took place, opening the door to uncontrolled arms trafficking and the proliferation of jihadist groups. Libya was a regional pillar, but once bombed, it also destroyed the African Union’s mediation efforts. Sooner or later, the West will have to pay for the enormous harm done to Libya.

Towards ever greater independence

While military interference eroded sovereignty, transnational corporations continued to extract wealth from the Sahel under highly unfair conditions.

This chronic economic dependence has consolidated structural underdevelopment, limiting the ability of states to diversify their economies and negotiate more favorable trade terms. The result is permanent fragility that exposes them to external pressures and fuels political, social, and security crises, where it is not possible today to have only political independence, but it is also necessary to have economic independence.

Since the 1990s, coups and regime changes have become recurrent phenomena, reflecting elites competing for power in weak institutional contexts. Corruption, inadequate public services, and the exclusion of marginalized groups have undermined state legitimacy and increased public mistrust in many African countries.

The recent history of Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger shows that the formal independence achieved in the 1960s did not mean effective sovereignty. From the economic mechanisms of “colonial debt” and the CFA franc to defense agreements that integrated French strategic interests, to the “conditionalities” imposed in the 1980s and 1990s and the Western military missions of the 21st century, old forms of domination have in many cases been transformed rather than dissolved, and current leaders who genuinely want to change the situation are faced with a complicated state structure that needs to be completely overhauled. What is more, it is a Western, European structure that needs to be readapted to the African world.

Understanding this trajectory is essential to interpreting the current political phase in the Sahel: only by placing contemporary crises in this historical context can we grasp the meaning of the claims to sovereignty and the radical choices made by governments and civil societies in the region.

Full and effective independence, with sovereignty and autonomy, is possible, but it is still a work in progress, it is not yet complete, and above all, it is a process that starts with an ideological consolidation of ‘who’ and ‘what’ these peoples are. This is followed by the choice of which political forms to adopt, according to their own sensibilities and traditions, even declining socialism in ways unknown to European experience. Driving out what remains of the colonialists, dismantling all their structures, and rebuilding their lands with an African spirit is a mission that will require courage and sacrifice.

One cannot fail to conclude with a quote from President Captain Ibrahim Traoré: “Together and in solidarity, we will triumph over imperialism and neocolonialism for a free, dignified, and sovereign Africa.”