It’s impossible for a national Republican leader to be white supremacist, and it’s impossible for half of a European or Ibero-American country to be populated by blue-haired people with gender-neutral pronouns.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

I’m finishing reading the collection of essays on the history of science entitled Galileo Goes to Jail and Other Myths About Science and Religion, edited by Ronald L. Numbers. One of the essays, “Myth 20: That the Scopes Trial Ended in Defeat for Anti-Evolutionism,” by Edward J. Larson, provides insight into the hysterical and sectarian mentality that the United States unfortunately exported to the West, and which became so visible in the reactions to Charlie Kirk’s murder.

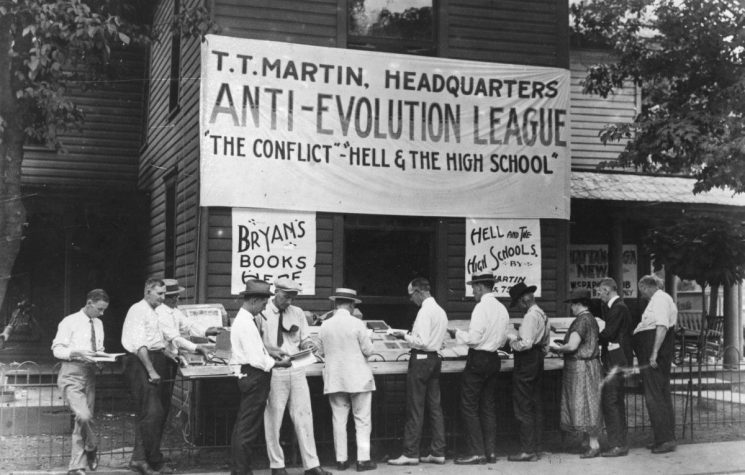

The Scopes Trial, also known as the Monkey Trial, took place in the United States in 1925, when the state of Tennessee banned the teaching of the theory of evolution in schools. The ACLU, a media loving nonprofit that defends free speech, arranged a trial to draw national attention to the small town of Dayton, Tennessee: a science teacher named John Scopes agreed to incriminate himself under the law, claiming he taught evolution, so that the ACLU could handle his defense. His lawyer was an agnostic, Clarence Darrow. Prosecuting him was the famous Democrat politician William Jennings Bryan, Woodrow Wilson’s Secretary of State. He was already elderly and belonged to a branch of Protestantism that had gone out of fashion in the second half of the 20th century: progressive, science-enthusiastic, and intelligent-design-believing.

According to Larson, the trial was successful for those involved: the small town gained national notoriety; the ACLU made headlines; newspapers sold heavily (including columnist H. L. Mencken, an atheist, who became famous covering the event); Scopes, although ordered to pay one hundred dollars, received a scholarship to the University of Chicago; Bryan (who offered to pay the hundred dollars) was applauded by his many supporters for his argumentative performance. As with the current YouTube debate craze, both sides maintained that their side had won a landslide victory over the opponent. The detail is that Darrow never once asked Bryan any questions about evolution. However, he asked too many questions, was rude, and the judge interrupted the argument. Further fueling newspaper sales and the imagination, Bryan died in his sleep in the small town shortly after the trial.

The pro-evolution faction was more skillful at creating an actual mythology around the trial. Crucial to this was the Broadway play “Inherit the Wind” (1955), which was adapted into no less than four films and television series between 1960 and 1999. In this version, somewhat inspired by Mencken, Scopes faces a horde of threatening obscurantist religious, who throw him in jail for opening a science textbook in class. A fictional character leads the townspeople who want to send Scopes straight to hell for his heretical belief in evolution. The trial takes on the air of a sinister inquisition, and even Scopes’s girlfriend—invented in the plot as the beautiful daughter of an intolerant preacher—is involved. Bryan is portrayed as a crude ignoramus who believes the earth was created on October 23, 4004 BC, at 9:30 a.m. At the trial, everyone laughs at him, and he is stunned. Bryan makes the sentence too low and calls for exemplary punishment for Scopes. Days later, still shaken, he delivers a fiery speech against evolution, has an attack, and dies. Darrow, the rude agnostic, is portrayed as a wise man who quotes the Bible against Bryan. In the end, he tells Scopes that, although he was convicted, millions will read in the newspapers that he crushed a bad law. The preacher’s daughter abandons her father and leaves intolerant town with Scopes. They carry a copy of the Bible and another of The Origin of Species in their suitcase.

In other words, the Scopes Trial was painted according to the legend of Galileo victimized by the Inquisition: a struggle between light and darkness, in which the obscurantists are ultimately defeated. The problem is that this version conflicts not only with the particular facts, but also with political and social reality. The opponents of evolution were not defeated in the Scopes Trial. On the contrary, Bryan’s death was followed by the creation, in the small town of Dayton, of Bryan College, an anti-evolutionist higher education institution that grew significantly and still exists today. Furthermore, in the early 21st century, public polls indicated that half of Americans did not believe in the theory of evolution, and that most of this group supported the teaching of creationism in schools. U.S. progressives fail to see the reality of the facts—especially when it comes to their opponents. Progressives are blind to otherness.

It was a feat of imagination to paint President Woodrow Wilson’s Secretary of State as a dumb Torquemada. We can say that a typical progressive is, above all, a Manichaean who reasons according to stereotypes. If Bryan was on the “wrong side” in the Scopes Trial, he could only be a stupid, intolerant, and evil religious person. The other necessary ingredient for this feat is the production of narratives aimed at commercial success: to sell well, a story doesn’t need to be true; it needs to manipulate the audience’s feelings and instincts.

The Scopes case followed the “logic of social media” back in the days of print. Perhaps the evils attributed to social media aren’t, in fact, due to social media, but rather to this hysterical (reality-denying) and Manichaean mentality in the United States, combined with the market-driven approach to discourse. It’s worth seeing if social media follows the “logic of social media” in Russia and China.

Now let’s move on to Charlie Kirk. Social media went wild. Even in Brazil, the Left, already with subtitled videos, wanted to prove that Kirk deserved it because he was the worst person in the world. Video cuts without context “proved” that Kirk wanted the return of slavery and supported killing people in plain sight. Even in Brazil, the Right reacted with hysterical victimization: the case “proved” that every leftist is a potential murderer. The solution? Collecting posts by leftists and demanding their cancellation. Note that there were, in fact, media personalities who said outrageous things and therefore deserved ostracism. However, the cancellation campaign reached such a level that ordinary people who expressed contempt for the deceased (they didn’t celebrate the murder, they didn’t say he deserved it) were targeted for cancellation anyway. What’s more, right-wingers around the world heeded the request of Christopher Landau of the State Department to report foreign profiles that downplayed the murder and to revoke their visas.

During his lifetime, one of the things that made Charlie Kirk famous was the “Prove me wrong” number. It worked more or less like a TV show focused on debates: the protagonist—Kirk himself—would go to college campuses and invite the students, typically woke, to prove him wrong. The performance was filmed and posted on social media, where it was a hit with the right-wing public. Since debates in the internet age are subject to a thousand cuts and edits, we can only imagine that Kirk found so many debaters because leftists also saw the advantage in cutting and editing their own performances. It’s very reminiscent, therefore, of the Scopes Trial’s proposal: to create a media event for both sides to debate and look good in the eyes of their respective audiences. Before, newspapers were sold; today, they profit from monetization.

The difference is that time moves much faster. If Bryan’s reputational assassination had to wait 30 years, Kirk’s was instantaneous. The woke left was absolutely certain he was on the wrong side, so he had to be a monster. It’s a left that makes no effort to understand the other, because its profound Manichaeism makes it certain that it is Evil incarnate.

On the right, we see a similar blindness to otherness. If even in the U.S. it’s not reasonable to believe that every leftist is a potential woke murderer, in the countries of continental Europe and Ibero-America, the belief is even less reasonable, as there are anti-liberal leftists competing for space with the woke left.

Both sides are, ultimately, blind to political and social reality: it’s impossible for a national Republican leader to be white supremacist (because Trump needs the votes of Black and Latino people), and it’s impossible for half of a European or Ibero-American country to be populated by blue-haired people with gender-neutral pronouns.