Epstein wasn’t a Democrat scandal or a Republican scandal. He was an intelligence scandal.

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

The public loves a villain. It gives us somewhere to point the finger, someone to shake our fists at, a name to pin to the dartboard. In the case of Jeffrey Epstein, half the country threw darts at Bill Clinton’s face, the other half at Donald Trump’s. And in doing so, both sides managed the remarkable feat of being right and wrong at the same time.

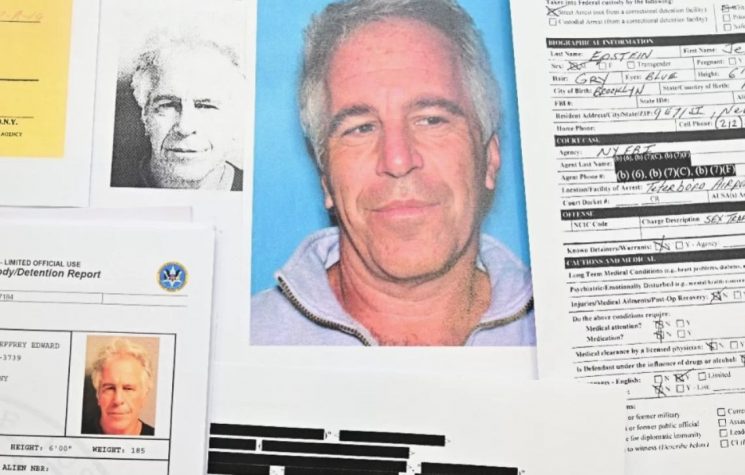

Because Epstein wasn’t a Democrat scandal or a Republican scandal. He was an intelligence scandal. And if there’s one thing the intelligence community does better than spycraft, it’s convincing the public that their worst behaviour is an isolated incident.

The reality is that Epstein’s CV reads less like “rogue billionaire” and more like “contract HUMINT officer”. HUMINT—human intelligence—is the art of acquiring sensitive information by exploiting human beings, and it’s as old as espionage itself. In the old days, that meant cultivating an “asset” through ideology, bribery, ego, or, when necessary, a little creative embarrassment. Blackmail was not an aberration; it was the business model.

The 1st Bush administration’s seduction of a senior Saddam Hussein insider in the run-up to the Gulf War is a perfect example. This is still not public knowledge, but a source that previously worked with special clearance gleefully recalled the tale, pleased it was such a “successful op”. The chosen target? The general’s own niece, who enthusiastically agreed to seduce her own uncle in exchange for an Ivy League education and a U.S. passport. She didn’t consider herself a victim. They convinced her this was just a wise and fairly standard price to pay if you wish to become upwardly mobile. When your workplace normalises such trades, you stop seeing the moral lines at all. Plus, incest is rarely frowned upon in elite circles; the Rothschilds even brag about their inbreeding so as not to “pollute” the bloodline.

This dark manipulation is hardly unique to the Americans. The KGB’s “sparrow schools” in the Cold War trained operatives — male and female — in the art of seduction, teaching everything from body language to pillow talk as tradecraft. East Germany’s Stasi infiltrated West German politics with so many “Romeo spies” that entire ministries were quietly compromised over candlelit dinners. The British, not to be outdone, ran “Operation Mincemeat” in WWII — feeding the Germans fake invasion plans via the corpse of a man dressed as a Royal Marine, complete with love letters from an invented fiancée to make the ruse more believable. The detail wasn’t just for flair; HUMINT works because it feels real.

Sometimes, the tools were even cruder. In the 1980s, the CIA quietly ran “compromising photograph” operations in multiple foreign capitals, sending attractive case officers or recruited locals to seduce embassy officials, then arranging for conveniently timed “hotel room maintenance” or “accidental” walk-ins by an agent with a camera. The resulting images, often staged to look far more salacious than reality, could keep an official compliant for years — no need to prove the indiscretion, just to make it plausible enough to ruin a career. In the game of kompromat, perception is currency.

Organised crime played the game too. The mid-20th-century alliance between the CIA and the Italian-American mafia was a perfect marriage of convenience. The mob controlled unions, docks, and gambling networks; the Agency controlled passports, prosecutions, and political pressure. Together they ran extortion schemes, some sexual, some financial, with a reach that extended from Havana nightclubs to Las Vegas casinos. When your “asset” already runs a blackmail racket, plugging them into HUMINT operations is practically turnkey.

Since the 1960s, if not beforehand, Israeli intelligence reportedly ran sexual blackmail operations in the United States targeting powerful figures tied to Middle East policy. Some accounts detail elaborate “honey traps” involving call girls, hidden cameras, and luxury apartments — the exact contours of the more famous Epstein operation that evolved from the same murky playbook. This isn’t conspiracy theory territory; former Mossad officials have openly acknowledged that sexual kompromat has been a “standard tool” in their kit. If Epstein’s Rolodex felt oddly international, this is why.

Epstein’s assignment was simply higher-end. Rather than seducing Ba’athist bureaucrats, he was hosting heads of state, royalty, and titans of finance in a world where everyone smiles for the cameras and everyone knows where the bodies are buried — because they helped plant them. His address book wasn’t a little black book; it was a nuclear deterrent.

Whitney Webb’s research makes this plain: Epstein was “middle management” in a sprawling transnational blackmail apparatus. His ties to billionaire Leslie Wexner gave him both funding and cover. His friendship with former Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak, and even financial connections brushing up against Benjamin Netanyahu, linked him to networks with decades of kompromat experience. Robert Maxwell — Ghislaine’s father and an asset of Israeli military intelligence — had been playing the same game back in the 1980s, helping shuffle secrets through the Iran-Contra affair. Epstein’s methods weren’t innovative; they were inherited.

Which is precisely why the infamous “Epstein list” is locked up tighter than Fort Knox. It’s not protecting one party from the other; it’s protecting the management from the stakeholders. A full disclosure wouldn’t just fry a few politicians — it would burn down the house. And the house, in this case, is bipartisan.

If you think this is all about illicit sex, you’re missing the real scandal. The women and girls were victims, yes — but so was the idea that state power exists to protect the public. Epstein’s blackmail economy only functioned because institutions at the highest levels, from the FBI to the State Department, ensured it could. In HUMINT terms, he wasn’t a “bad apple”; he was a dependable employee.

The technology may be changing, but the instincts remain the same. In the old world, you needed an Epstein to lure, trap, and control. In the new world, you just need Palantir. This Peter Thiel–backed data-mining giant can hoover up your emails, your location history, your purchases, and your social media likes and cross-reference them to identify exactly what lever to pull if they ever want you compliant. No need for grainy VHS tapes when your browser history is infinitely worse.

Meanwhile, the financial system is being rewired for maximum control. Webb points out that under Trump, the “Going Direct” plan — crafted with BlackRock — shifted vast wealth upwards during COVID. Now, stablecoins and central bank digital currencies are being sold as “innovation”, but in practice, they will allow financial institutions to freeze or redirect your assets as easily as they deplatformed inconvenient voices during the pandemic. The blackmail file has simply become your bank account.

And yet, the public is still hypnotised by the partisan pantomime. The left rails at Trump’s Epstein ties. The right rages about Clinton’s. It’s like arguing over whether the getaway driver wore loafers or trainers while ignoring the fact you’re still tied up in the boot. The fixation is the point — it keeps people from asking who planned the robbery.

The bleak truth is that Epstein’s story is not extraordinary inside the intelligence world. He was part of a tradition that has included mobsters, media moguls, war criminals, and honey-trapped relatives — all of them “useful” to their handlers. The only thing that changes is the set dressing. One decade it’s a superyacht, the next it’s a private island, the next it’s a Silicon Valley data vault.

But here’s the good news: understanding this is the first step to disarming it. Once you realise the “Epstein scandal” is not about one man but about a system—and that this system thrives on your division, distraction, and dependency—you stop chasing the laser pointer.

The answer isn’t waiting for some congressional committee to release the files; they won’t. It isn’t voting harder for one faction of the same machine; that’s just changing the colour of the wallpaper in the panic room. The answer is building parallel systems: local economies that can’t be frozen at the flick of a switch, independent journalism that can’t be bought, and technologies that decentralise rather than centralise power.

We still have tools: economic boycotts, collective action, the BDS model of targeted financial pressure and general strikes if we could stop being distracted by the nonsense perpetually churned out and instead just cohesively say no more. The fact that such tactics provoke panic in boardrooms and state offices should tell you they work. And most importantly, we have the ability to refuse the framing — to stop letting the powerful choose our enemies for us.

Epstein was not the disease; he was a symptom. And symptoms can be useful. They tell us something’s wrong if we’re willing to read them honestly. The cure is not blind trust in the same institutions that hired, trained, and protected him. The cure is refusing to live in their reality tunnel.

Because while they want you to believe the world is a nest of snakes, most people are not plotting to blackmail the owner of the local laundromat for leverage in the great fabric softener turf wars. That paranoia belongs to the intelligence culture — and it’s only contagious if you let it be. Ordinary people can build an ordinary world again. Which, given the alternative, would be the most extraordinary rebellion of all.