Who will fight the war that the EU wants to wage against Russia?

Join us on Telegram![]() , Twitter

, Twitter![]() , and VK

, and VK![]() .

.

Contact us: info@strategic-culture.su

The game risks breaking down

Italians do not like the United States, which is why they are forced to hate Russia. It is a matter of choice, not just taste. For Giorgia Meloni’s government, the darling of the Aspen Institute decorated by the Atlantic Council, the people must correct their preferences and align themselves with the will of those in power. And, let’s be clear, those in power do not reside in Rome.

It is the same rhetoric that has been used since Italy became a republic: the master gives an order, the servant must obey. This is the only option. When this is not done according to the criteria indicated, the master complains, and the vassal, who controls the servants, undertakes to resolve the inconvenience.

Let’s give a look to the “classical” strategy for this kind of situation.

If a political power wants to impose its influence on a foreign country, it needs to obtain not only the obedience of its institutions, but also the consent, or at least the neutrality, of public opinion. When the goal is to make people love the United States and at the same time generate hostility toward Russia, explicit propaganda is not enough: a sophisticated strategy of infowarfare and cognitive warfare, i.e., a war fought not with weapons but with narratives, symbols, emotions, and perceptions, is needed.

The first step is to restructure the general narrative framework: the United States must be perceived as a civilizing force, a guarantor of democracy and rights, while Russia must be associated with regressive, authoritarian, and militaristic values. The narratives must be simple but powerful: NATO as the defender of free peoples; Moscow as a constant threat to the global order.

This narrative work is accompanied by a long-term cultural strategy based on the use of soft power. The aim is to instill in citizens, especially young people, a positive perception of the United States through cultural products—TV series, music, sports, technology, fashion—that make identification with the American lifestyle desirable. The idea is that ‘living like an American’ is synonymous with being modern, free and fulfilled.

On a linguistic level, the semantic war is being waged, like the transformation of the meaning of key words. Those who challenge American influence can be labeled ‘pro-Russian’, ‘conspiracy theorists’ or ‘anti-Western’. At the same time, terms such as “freedom,” “democracy,” and “peace” are redefined to coincide with the Atlanticist line. NATO, even though it is expansionist and aggressive, is presented as a defensive shield, while every Russian move is described as a provocation or threat.

An essential component of this strategy is the penetration of the education system and digital media. Students must learn to perceive the Cold War as a moral battle and the present as its continuation. Social networks are colonized by influencers, NGOs, and think tanks that convey a worldview consistent with the pro-American narrative, but with youthful, seemingly neutral, or progressive language.

At the same time, historical memory is being manipulated. The aim is to erode Russia’s image as a liberating power in World War II and instead reinforce negative memories associated with communism, the KGB, and repression. Cultural ties with the Slavic world are devalued and selective commemorative celebrations—such as those for the victims of the Soviet regime—are promoted to crystallize a hostile collective memory.

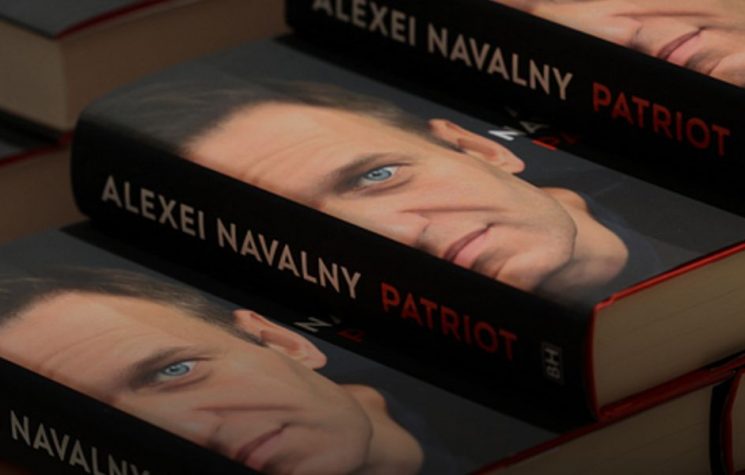

Meanwhile, Russia is subjected to a continuous process of demonization. Every scandal, incident, statement, or crisis involving Moscow is amplified, stripped of context, and used to reinforce the image of a violent, corrupt, dangerous enemy. News about internal corruption, political assassinations, espionage, or repression of rights is used as material to consolidate symbolic hatred.

Finally, to consolidate cognitive victory, consensus engineering is employed. Polls are produced showing broad support for the Atlanticist line. The media constructs false debates in which divergent opinions are ridiculed or marginalized. Dissent is delegitimized as deviance or treason. Those who do not toe the line are silenced or exposed as “internal enemies.”

The ultimate goal is to make the perceived national interest coincide with the American interest. Once a population truly believes that what is good for the United States is also good for them—and that Russia, by definition, is an existential threat—the cognitive war is won. There is no longer any need to repress or convince: the perception of the world, and therefore also political reality, has been successfully shaped.

On the wrong side

The trouble, here, is that there is a generation gap. Today’s young Italians feel no moral obligation towards the US military, partly because the image of the United States has been deeply compromised by bloody wars and support for some of the most violent regimes on the planet. A well-known Italian academic once said that if the United States did not exist, we would have been spared 95% of the wars in the world. Perhaps he was not entirely wrong.

Meanwhile, Italy is preparing to lose billions of euros due to Trump’s tariffs, while investing just as much to purchase US weapons in compliance with European Commission directives, both through ReArm Europe and SAFE.

It is a real cognitive bias. The political class is pushing the entire country towards war by selling this choice as the road to peace, while the younger generations are not motivated to follow this course because they do not believe in the state, have no sense of political belonging, and are not morally prepared to support such a situation.

On the other hand, the problems are objective. The Italian Armed Forces do not have the capacity to absorb the enlistment touted by the government; young people, who have grown up on TikTok and Instagram, have no intention of compromising their lives for something ephemeral and devoid of moral value. So, what to do?

It is a problem of education or, if you will, of cognitive social engineering: we must convince citizens to love those they hate. And, consequently, for the equation to work, we need to find someone else to hate. That ‘someone’ is Russia.

The rhetoric of the First Republic was based on a positive sentiment: admiration for the United States. In contrast, the current rhetoric, embodied by the Mattarella Republic, is based on a negative impulse: hostility toward Russia. The problem is that this hostility is not reflected in the sensibilities of the population. First, because, despite intense media activity, many Italians perceive NATO as an aggressive, unscrupulous, and ever-expanding alliance, heedless of other people’s “red lines.” Second, because no Italian is willing to sacrifice themselves for NATO, which is seen as a distant entity with no roots in the national culture.

According to a Censis poll conducted on December 6, 2024, a large majority of Italians (66.3%) blame the West, and in particular the United States, for the conflict in Ukraine. The prevailing perception is that Russia is right and NATO is wrong. As a result, the transition from the rhetoric of an alliance based on love to one based on hatred is not producing the results Washington had hoped for. As a result, the Italian government, with Giorgia Meloni and Guido Crosetto at the forefront, seems to be preparing for a military confrontation with Russia in the absence of real popular consensus. If the younger generations cannot be educated to idolize the United States as they were in 1945, attempts are now being made to lead them to dislike Russia.

Since Italy is embarrassed by its subordination to a foreign power, it has built up a rhetorical apparatus over time to sugarcoat this condition. For decades, this rhetoric has been based on the myth of “liberation” from fascism by the United States. However, with the passage of time and the gradual disappearance of the partisans, historical memory has faded and with it the emotional link to those events.

Today’s young people no longer feel that link. For them, the United States is associated more with images of Gaza than with the Normandy landings. The perception of the present has overshadowed that of the past. This situation poses a real challenge for the media system, which must invent a new narrative to justify US influence in Italy.

When the game is in danger of breaking down, the government has a problem on its hands. Who will fight the war that the EU wants to wage against Russia?